In 2014, ISIS rapidly and brutally seized control of parts of northeast Syria, establishing a well-structured proto-state in the wake of these advances. Among ISIS’ 23 governing authorities, its education ministry, or Diwan al-Taalim,[1] was responsible for overseeing education in ISIS-controlled areas.

Relying on existing research, official databases, the voices of individuals directly affected by ISIS, insights from Syrian and Syrian-Kurdish educational experts, local officials and educators, and ISIS educational materials, including textbooks, the following chapter examines the significant impact that ISIS had on the local education sector in northeast Syria. It explores the impacts on the curriculum as well as teachers and students in areas under ISIS control from January 2014 until the group’s territorial collapse at Baghouz in 2019. The chapter also analyses the enduring consequences for education in the region.

Background

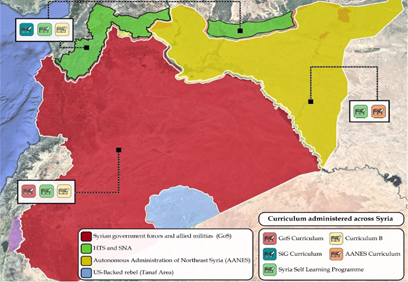

The protracted post-2011 conflict in northeast Syria has had a profound, far-reaching impact on the local education system, particularly because of the period of ISIS rule between early 2014 and 2019.[2] During its rule, ISIS held significant territory in northeast Syria and imposed an extreme interpretation of Islamic law that also manifested itself within ISIS’ education policies.

ISIS used education as a tool for indoctrination to shape a new generation of supporters, commonly referred to as the “Cubs of the Caliphate.” The group established the Diwan al-Taalim, which was run by the group’s hisba units. The department implemented a highly ideological educational policy that drastically changed the educational curriculum, the lives of students, and the role of teachers.[3]

Those who did not conform to the rules were punished, leading in many cases to the abduction and killing of educators, students, and their families. Under ISIS, schools, universities, and educational institutions were destroyed, contributing to the displacement of millions of students and educators. Although ISIS retreated from northeast Syria in 2019 following its territorial defeat at Baghouz in Deir Ezzor,[4] widespread repercussions of its rule are still felt today. According to UNICEF, as of 2022, over two million children between the ages of five and 17 in Syria were still out of school, with a significant number concentrated in the country’s northeast.[5] Furthermore, an additional 1.3 million children were at risk of dropping out of school in 2019 while approximately one in three schools were closed nationwide.[6]

Methodology

To illustrate the story of how ISIS rule affected education in northeast Syria, this chapter relies on a combination of data sources. First, the research team conducted a thorough examination of open-source databases, research papers, reports, and newspaper articles. Copies of textbook materials and public memoranda shared with students and teachers by the Diwan al-Taalim were also examined. While this information is valuable, much of this literature does not consider the perspective of affected individuals and communities.

In the second stage of research, the voices of affected individuals in Syria were collected through KIIs; they comprised a range of community members, including thirteen current and former teachers, three education officials, a civil council member, a former student, the wife of a former teacher, a pensioner, a freelancer, a grocer, and an international expert.[7] It also included a series of eleven focus group sessions comprising a total of 87 participants. This qualitative data was collected by RDI, with one local research partner from RDI conducting and translating all 23 interviews. Interviews and focus group sessions covered four governorates in northeast Syria (and at least eight cities within those governorates): 1) Aleppo (Kobane and Manbij); 2) Hasakeh (al-Qahtaniyah,[8] Qamishli, al-Shaddadah, Tal Brak); 3) Raqqa (Tabqa and other undisclosed locations); and 4) Deir Ezzor (Hajin and other undisclosed locations).[9] Interviews of affected persons were primarily retrospective accounts of their experiences during ISIS rule but also included their more recent experiences. The language used for these conversations was predominantly Arabic, with some conducted in English. Eight of the 23 KIIs were conducted with female participants.

Due to safety restrictions related to accessing certain regions in northeast Syria, interviews were conducted through a combined written and oral approach. In most interviews, the local RDI researcher first shared the interview questions with the interviewees. Then, interviewees responded in writing, before the local researcher conducted a follow-up phone call or WhatsApp chat to consolidate the information, ensure proper interpretation, and delve into specific questions if needed. In addition to safety issues, some affected persons who were contacted for interviews refrained from further involvement in the research for various reasons including fear of being named, while others were unable to connect with the local researcher due to local internet connectivity issues.

Finally, some topics were included in the interview protocol but did not receive a lot of coverage in this chapter. According to local researchers, this was possibly because they were too sensitive for affected people to discuss. One such topic is the destruction of schools and educational institutions. For example, an article from the North Press Agency reported that anti-ISIS battles by the SDF and US-led Coalition in Raqqa led to the destruction of a staggering 80% of the city’s infrastructure, citing UN figures indicating that 11,000 buildings were either destroyed or damaged between February and October 2017.[10] However, since damage was at times caused by the SDF and the US-led Coalition themselves, and not just ISIS, few residents were willing to discuss the topic for fear of being seen to criticise the SDF in post-ISIS northeast Syria.[11]

ISIS’ impacts on northeast Syria’s education sector

Based on analysis of existing literature, interviews and focus group sessions, this chapter is grouped into four main areas: 1) teachers and teaching; 2) curriculum and textbooks; 3) students and learning spaces; and 4) lasting impacts.

Following repeated threats and financial incentives, I found myself with a beard [in order] to become a model teacher under the radical group.[12]

Teachers and teaching

The teaching profession changed drastically under ISIS’ rule in northeast Syria, with many teachers fleeing to neighbouring countries or regions to escape.

The role of teachers

[The role of the teacher] was to deliver what was dictated to them without any personal diligence or information outside the curriculum.[13]

ISIS’ takeover of the education system in northeast Syria drastically changed the role of teachers. Teachers became, or were forced to become, implementers of Salafi-jihadi doctrine as promoted by the new ISIS curriculum.[14]

As one male teacher from Kobane described, “Teachers were employed as an instrument through which ISIS’ ideology was implemented to change the minds of students.”[15] This was reiterated by a formal announcement made bytheDiwan al-Taalim in May 2015:

Indeed, the ummah excels through its teachers when they direct what they have assumed responsibility for with truthfulness and trustworthiness…So the importance of the teacher is to polish minds, refine souls, implant virtues and tear out vices, and to educate [future] generations with an established, correct education for that is among the qualities of the prophets.[16]

In ISIS-controlled territories, teachers were forced to make a choice: either leave their homes or pledge allegiance to ISIS. Over 140,000 educational personnel residing in ISIS-controlled territories in both Iraq and northeast Syria therefore left their posts once ISIS arrived, either to join ISIS as fighters or to flee their regime.[17] Many teachers fled to other areas of control within Syria (including Latakia, Hasakeh and Qamishli[18]) fearing ISIS brutality or repression on the one hand, or military conscription or other forms of maltreatment that may be at the hands of the Syrian government in government-controlled areas.[19] In a focus group session in Kobane, a teacher described how he and other teachers fled to Turkey for several months following a massacre on 25 June 2015.[20] He added that when students returned to school, there was a shortage of teaching staff across northeast Syria as many teachers stayed in Turkey, creating longer-term repercussions for the local education sector.[21]

Teachers who stayed on after the arrival of ISIS in the area were often forced to remain due to financial reasons. With the takeover of parts of northeast Syria by ISIS, teachers’ wages were cut by the Syrian government, leaving most of those who did not make the move immediately with little to no financial resources to migrate. One male former teacher from Tal Brak in Hasakeh described how he “stopped receiving wages in 2015 and then stopped teaching altogether in 2016.”[22] He explained how the teachers who did stay on became little more than conformists:

Since ISIS could not create a new cadre of educational personnel and teachers for its “caliphate,” it had to rely largely on existing personnel and teachers. Teacher innovation and autonomy was no longer allowed. Previously, in universities, students studying to become teachers were told that the teacher was given a kind of freedom to move away from the textbook and teach according to the culture of the [local] area. This was no longer the case under ISIS. There was no space for innovation from the teachers. Teachers were required to follow the textbook exactly as it was written.[23]

Additionally, all teaching was required to be in Classical Arabic, the language of the Quran. All other languages of instruction were forbidden since they were the “language of the enemy.”[24] One exception was English, which was only taught to foreign students living in ISIS-held areas.

A male teacher from Hajin in Deir Ezzor described the changed realities of being a teacher under ISIS:

The main role assigned to the teacher under ISIS was to instil jihad and extremist religious bigotry into the brains of [students] to prepare them for the path of God, whatever the circumstances. Before ISIS, teaching and education was different in the sense that teachers felt safer; they were not exposed to any pressures from anyone.[25]

Another male teacher from Hajin described teachers under ISIS as changing from an esteemed role model in society to instead becoming mamlouk (servants or subordinates) who could not disobey their masters. He added that teachers of Islamic subjects were not accepted as qualified teachers by ISIS since they “graduated at the hands of scholars who did not apply the approach of the [Prophet, Peace Be Upon Him].” [26]

A former student from al-Shaddadah reported that all male teachers were required to wear a long robe and full beard,[27] further moulding educators into this new role and to visually represent their commitment to ISIS’ interpretation of Islam.

Teacher re-education and repentance

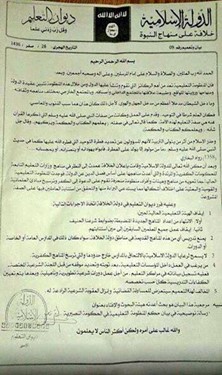

Under ISIS, teachers’ professional development only involved religious re-education. In December 2014, the Diwan al-Taalim announced that schools would be required to undergo mass ideological and religious re-education and “repentance” to ensure that all teachers were in compliance with the caliphate (see Box 1).[28] This included instructing teachers to ‘arm students with memorizing Quranic verses and hadith [teachings of the Prophet Mohammed, Peace Be Upon Him] reports to support what they believe’ and stressing the ‘strengthening of creed in their hearts and their responsibility to proselytize to others.’[29] Under ISIS, one focus group participant said, “the teacher was considered an infidel. No one dared to say they were teachers originally.”[30] Therefore, they were forced to repent completely and re-educate themselves on how to serve ISIS as teachers of the Quran.[31]

Repentance was completed by attending a formal session at a mosque where teachers proclaimed their repentance to God by signing an official document. Those who did not attend were ‘considered as insisting on [their] apostasy, and in this regard, the relevant Shari’a judicial proceedings [were] applied.’[32] Teachers who did not comply were fired and shamed through public announcements where their names were listed and disseminated as having rejected Salafi-jihadithought.[33] A former female teacher from Deir Ezzor described the religious repentance courses in her region:

Teachers were invited to have a religious discourse. This lasted for a month. In my area, we spent a whole month undergoing a course in the mosque. On the ground floor were male teachers, and on the first one, there were females. Every day after al-Asr [afternoon prayers] until sunset, we attended the course. Friday and Saturday were off. At the end of the course, there was a test. Even university graduates had to pass it. If one failed, he/she would not be entitled to teach.[34]

Occasionally, repentance was required if ISIS suspected that a teacher had some form of affiliation with the Syrian government. One focus group participant in Raqqa recalled a situation he witnessed when a professor was accused of being a regime collaborator, and that employees were forced to undergo a 20-day repentance that included memorizing “certain verses and religious matters taught by the extremists to the people.”[35]

A male teacher from Hajin described the repentance oath-taking for teachers:

All teaching cadres were gathered inside a mosque for three hours daily over a period of 15 days. They had lectures as if they [the teachers] had been infidels and reneged on Islam. It was an attempt by the group to instil ignorance in teachers and exploit their need to know more about Islam…They were asked to memorise one of the 30 parts of the Quran. Then, ISIS publicly declared that these teachers had repented, and they were no longer misguided. These courses were not intended to raise the level of teachers educationally or culturally, but [were intended to save] the misguided.[36]

Box 1. Call for Repentance of Teachers (Nineveh Province: December 2014)[37] [translation]  “Indeed, the educational system is considered among the most important centres that states establish and cultivate, and through this system is made clear the ideology/creed of the state, its program, its consideration of the situation, as well as the nature of its relations with internal society and its classes, and external society in its varying directions and cultures. And Satan has not found a greater entrance than the entrance of ignorance and arbitrary whim, and this has been among the most important causes of misdeeds and rebellion. For knowledge has been a condition of tawheed and among the qualities of the Prophet (PBUH) that the Quran mentioned about him was the quality of teaching this Ummah, as the Almighty said in describing him: “Who may teach them the Book and wisdom to purify them” [Quran 2:129]. And the One whose affairs are exalted said: “Who may teach you the Book and Wisdom.” And Islam has warned about the influence of those who take charge of education for themselves because they are the ones responsible for tampering with the inborn-nature of tawheed that God has endowed as related in a hadith of the Prophet [PBUH]: “Every child is born with true faith. It is the parents who make him/her Jewish, Christian or Magian”—Bukhari 1358. After God Almighty enabled the Islamic State and it announced the Caliphate, it has directed attention towards the programs of the ministries of education affiliated with the kafir and apostate governments that have been reckoned to be programs attempting to separate religion from state, so the current educational system has been found to be…a decadent program establishing the call to kufr and establishing the principles of secularism, nationalism and Ba’athism in its various forms—something that calls for disavowal of it and the realization of the call for repentance from those working in it on the legal level. Thus, the Diwan al-Taalim has decided to adopt the following measures: 1. Putting a stop to the current educational committee for now: a) Ceasing the preparation of the new educational programs bound by the restrictions of our Hanif [renunciate] law. b) Stopping the work of all prior teachers until the fulfilment of the call for their repentance. 2. None of the old educational programs are to be taught in the areas of the Caliphate, whether public/private schools or lessons. 3. Citizens of the Islamic State are not allowed to attend schools outside its borders and which establish principles of disbelief. 4. Whoever wishes to work in the educational foundations: after his repentance, and definition of his stance before the special Shari’a Committee, he must record his affirmations in the education centres, to undertake developmental and qualifying Shari’a sessions. After that the educational qualifications of each according to his speciality will be completed. 5. The one who contravenes this statement for distribution will be subject to judicial inquiry, with the coming down of deterrent consequences according to Shari’a for him. Note: The authority of this statement is the result of an investigation prepared by the al-Eftaa [offer Islamic guidance/ruling to Muslims] and Buhuth [research] Committee,[38] under the title: “Clarification Message on the Statement of Judgment on the Education System in the Nusayri government.”[39] And God is Predominant over His affair but most people do not know it.” Note: Although this document was published in Iraq’s Nineveh province, the same conditions applied to ISIS-controlled area of northeast Syria. |

We ask you to attend a qualification session for teachers in aqida [creed] and fiqh [jurisprudence], and the teacher will be granted at the end of it a qualification document to teach in public schools. Whosoever refrains from the session will be barred from undertaking any teaching activity or work in the lands of the Islamic State.[41]

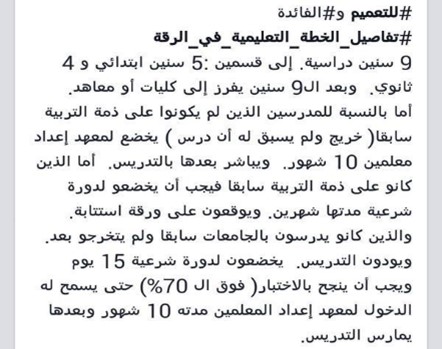

Additionally, those in university studying to become teachers had to undergo a ‘Shari’a session lasting 15 days’ and ‘pass a test with a score over 70%’ before completing a 10-month course with ISIS’ Institute for the Preparing of Teachers.[42] Teacher training sessions involved lectures on subjects from the previous Syrian national education curriculum that were now forbidden, including supposedly “blasphemous” lies in science books accused of questioning Islamic beliefs about the origins of humankind, such as Darwin‘s theory of evolution.[43] Lectures were reportedly delivered firmly, and often with shouting, a way of inciting fear among teachers.[44] Most re-education campaigns were led by armed brigades and those who did not abide by the strict regulations faced threats of public execution. Some were executed.[45]

Box 2. Educational Plans in Raqqa Province (indirect testimony: via local pro-ISIS Raqqa Islamic News Network [RNN])[46]  “For general distribution and benefit: Details of the educational plan in Raqqa: Nine years of study: in two divisions. five primary, four secondary. After the nine years, selection for colleges or institutes. As for teachers who have not previously had an education qualification (graduate with no prior teaching experience), there is subjection for 10 months to the Institute for the Preparing of Teachers. And after that there is direct entry to teaching. As for those who have previously had a teaching qualification, they must undergo a Shari’a session lasting two months, and they sign a document calling for repentance. As for those who have been previously studying in the universities but have not yet graduated and would like to teach, they are subjected to a Shari’a session lasting 15 days and they must pass a test with a score over 70% that the person may be allowed to enter the Institute for the Preparing of Teachers for a period of 10 months, after which the person may teach.” |

Inciting fear among teachers

ISIS’ main strategy for controlling what was taught was the ‘infusion of terror by means of extreme violence and fear throughout all educational components.’[47] There are numerous accounts of ISIS officials inciting fear among teachers in northeast Syria, but a common thread throughout was the gruesome nature of punishments given to those who did not abide by ISIS’ strict rules. In one focus group session, the father of a teacher explained:

We suffered academically. My daughter, who was a teacher, left the school; my son, who was an employee, also quit his job out of fear of ISIS.[48]

Grass-roots educator Lamiaa Suleiman received a great deal of attention in the media for establishing the Khotowat Foundation for Social Development to secretly keep teaching under ISIS rule.[49] In an interview with SceneArabia, she described their work:

We started working underground, in homes, in mosques, in cellars […] it didn’t matter where we were, but just that education continued in some way or another, outside their indoctrination camps.

Suleiman’s network started in Deir Ezzor and expanded to include more than 80 educators throughout the region, secretly teaching students reading, mathematics and English while also offering psychosocial support. Aware that the teachers could be abducted or tortured for educating students outside of the ISIS curriculum, Suleiman and her teachers coordinated remotely using encrypted messages without revealing any information about the members of the network to each other.[50] However, ISIS did learn about the Khotowat Foundation and threatened the lives of those involved.[51]

A similar account was reported by a former female teacher in Deir Ezzor who had her own story of defying religious law:

Once, the hisba members entered the classroom. At the time, my face was not fully covered. They protested and wanted to take me forcibly out of the school to their offices. I refused to obey saying if I put on a face veil then the pupils would not hear me well; this impinges upon sound articulation. Then they protested why I had my gloves off, I replied that it is impossible to have chalk and write on the board with a glove. At the end, they made me [swear on the Quran] not to repeat such an action.[52]

In addition to the fear ISIS incited among those in civil society networks like Suleiman’s in Deir Ezzor, there were multiple reports from across northeast Syria of teachers and educators who were publicly executed. These executions were often for actions deemed to be in defiance of ISIS’ rule, such as refusal to teach the new curriculum. Executions sometimes took place in front of students.[53] In another account, a teacher reported that ISIS also forcibly took possession of the homes of teachers who defied ISIS policies.[54]

Teachers who had connections to the Syrian government could be fatally punished. One interviewee from Deir Ezzor described how teachers who were still receiving public sector salaries from the government in the early days of ISIS rule were brutally executed. He stated: “A number of people were killed—including my friend from Hawayej Ziban, who was a teaching assistant at al-Furat University. He was killed and crucified.”[55]

Another teacher from Kobane remembered how one of the teachers from his village was also killed:

In 2015, [a teacher] was killed in Sarrin under the pretext of teaching related to infidels with the Syrian regime. He was from the village of al-Ayouj [Sarrin, Kobane]. He had just returned to Aleppo, where he received his monthly salary. He was taken from his home.[56]

The journey to Aleppo to receive salaries was dangerous for teachers still working under the Syrian government. A mother of boys recounted how her husband, a former teacher in Kobane, went missing and was never found. In May 2016, her husband and 13 other teachers were headed to Aleppo to receive their monthly salaries to avoid forced dismissal—a requirement from the government that served to assert its continued presence in the region. However, ISIS spotted the teachers:

[The teachers and my husband] were arrested on Qara Qozaq Bridge on the Euphrates River. After two months in captivity, [my husband’s nephew] was released. He told us that they were held in the former cultural centre in Manbij, which ISIS had turned into a prison.

One day in the afternoon, we were told that the abducted teachers would be freed. We gathered. We heard they had reached the security checkpoint at the village of Qomji where the Autonomous Administration would ask them a set of questions. But [the teachers who were abducted] never came.[57]

This type of punishment and abduction was not limited to schoolteachers. It also applied to school principals as well as other educators, scholars, and anyone else that ISIS deemed had the potential to influence young minds. A participant from a focus group session in Deir Ezzor described how ISIS raided and stole furniture in schools where principals were seen to have links or direct contact with the Syrian government. In some cases, these principals were forced to join ISIS.[58]

Scholars were also punished for protecting history that was deemed anti-Muslim. In 2015, Khaled al-Asaad, a Syrian scholar, was beheaded in Palmyra for refusing to lead ISIS to valuable, historical artifacts that the group viewed as un-Islamic “idols” that should be destroyed.[59] Two years later, in 2017, a group of 12 Syrians, many of them teachers, were also publicly executed in Palmyra, although the reasons for this execution were not clear.[60]

Physical acts of torture and murder contributed to the building of feelings of constant fear among teachers. The main message from ISIS was to obey or be punished; there would be no middle-ground.[61]

A teacher from Tal Brak in Hasakeh summarised the shared experience of fear and torture among teachers:

Teaching has [historically] been [an honourable] mission. Knowledge has been the key to progress and success. However, such an experiment [under ISIS] served as a turning-point, not for me personally, but for all teachers and students who experienced [life under ISIS]. We were engulfed by fear and horror. [ISIS] sought unsparingly to instil radical ideas and ideology into our brains. Partly, they were successful in moulding minds, sowing sedition, and creating rifts among people through sectarianism and jihad, which they advocated relentlessly to install their so-called state.[62]

Curriculum and textbooks

[ISIS] did not keep any former book or subject.[63]

The curriculum played a pivotal role in ISIS’ strategic agenda, serving as an instrument for indoctrination and the dissemination of the group’s extremist ideology. Prior to ISIS’ presence in the region, the Syrian government’s curriculum was widespread throughout northeast Syria.

A Christian male civil council member shared how, in his area of al-Qahtaniyah:

The Syrian education system was very good. All Syrians [from different backgrounds] agree on this issue. Kurdish, Arab and Syrian students attended these schools and got a wonderful education.[64]

Another male teacher from Hasakeh agreed, stating:

All Syrians, regardless of their [religious or ethnic] backgrounds were in the same classes. No preference was given to one over the other. Words like Kurds or Arab [in the context of school curricula] were not used.[65]

Contrary to these views, Kurdish journalist Sardar Mlla Darwish, in an article on the state of education for Kurds in northeast Syria, noted that for decades prior to ISIS, ‘Syrian Kurds have endured a ban on speaking and studying in their mother tongue as a result of political pressure and repression from the Syrian regime.’[66] The Kurdish Project similarly reported that under the Syrian government, ‘Syrian Kurds were not allowed to use the Kurdish language, were not allowed to register babies with Kurdish names, were not allowed to attend private Kurdish schools, and were banned from publishing books or other written materials in Kurdish,’[67] leaving Kurds with limited access to an education if they were unwilling or unable to learn in Arabic.

However, with the arrival of ISIS, the government’s curriculum in general was abolished.[68] ISIS textbooks and instructional materials were systematically infused with propaganda and ideological messaging, reflecting the group’s radical interpretation of Islam. Notably, the curriculum was heavily militarised, with a primary focus on training young individuals to become active fighters in the group’s ranks.[69]

Through the analysis of collected data, two prominent sub-themes related to the curriculum and textbooks emerged: a) ideology and the militarisation of pedagogy; and b) textbook reforms and curriculum developers. These sub-themes shed light on the fundamental aspects of the curriculum reforms under ISIS rule, which in turn provide valuable insights into the group’s systematic manipulation of education for ideological purposes.

Ideology and the militarisation of pedagogy

In introducing its own highly ideological curriculum, ISIS overhauled the diverse range of subjects that once formed the basis of the Syrian curriculum. Music, physical education, nationalism, law and philosophy were among the subjects banned by ISIS in their efforts to reshape educational curricula within schools and universities.[70] This process of overhauling the curriculum was carried out in stages, as described by a male education official from Deir Ezzor:

When ISIS ordered schools to be reopened, it initially eliminated core subjects with the exception of mathematics and reading. This transitional phase lasted for approximately four months, during which time the existing curriculum was annulled. Subsequently, a new curriculum was introduced, accompanied by newly printed textbooks that were distributed to schools. The [new] ISIS curriculum included subjects such as reading, [mathematics], Islamic education and Quranic studies, which were taught in the initial stages. Later, subjects such as jurisprudence, creed, Quranic interpretation [tafsir] and traditions were introduced for higher stages.[71]

Furthermore, the curriculum focused on religious studies, including memorisation of the Quran, hadith and other Islamic texts, while also promoting extremist views about violence, jihad and the establishment of an Islamic state. One focus group session participant explained:

[ISIS] tried to manipulate children using all means possible, and they succeeded. If you wanted to work in the field of education, it had to be done secretly out of fear of them. The goal was to brainwash children.[72]

The impact of ISIS’ curriculum extended beyond the restructuring of subjects. Education became a domain for exclusively promoting the group’s interests, revolving around concepts of jihadand paradise.[73]The curriculum was also a recruiting tool that targeted unemployed youth with promises of material possessions, power, and leadership positions.[74] The indoctrination process was pervasive, aiming to mould the minds of individuals and instil a distorted understanding of Islam. ISIS’ curriculum actively propagated violence, advocating for armed conflict and endorsing acts of terror.[75] A male teacher from Tabqa explained this by stating: “They changed the textbooks to be able to insert their ideology into the minds of children. The aim was to recruit the kids as the ‘Cubs of the Caliphate’.”[76]

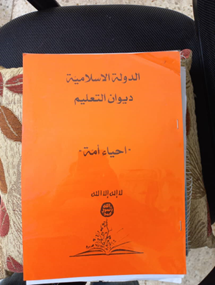

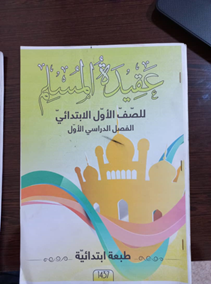

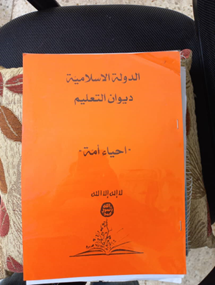

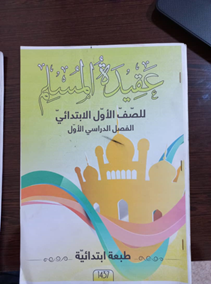

As such, ISIS placed a particular strategic emphasis on primary schooling as an entry point for disseminating their interpretation of Islam.[77] Educational standards were notably low, with mathematics stripped down and subjects such as physics and chemistry later banned.[78] Figure 1 and Figure 2 demonstrate the kind of Islamic textbooks introduced by ISIS in these early stages.[79] The titles of the books alone show that the focus of education was largely on the significance of the ”caliphate” and Islam.

ISIS used the militarisation of pedagogy, which can be defined as incorporating military themes and practices into the education system, to instil its values among youth in northeast Syria.[80] This included the use of military-style uniforms and disciplinary systems.[81] ISIS even offered classes and programmes that were designed to prepare students for combat, with recruiters invited to speak with students and promote careers in their battalions. Violence and aggression were regularly hailed as a means of problem-solving within ISIS pedagogy, as was the marginalisation of alternative views and value systems. Elaborating on this, a former school owner explained how:

They did not allow us to open private schools. I remember when I used to smoke, one of the children told me that he would report me to “the brothers” [ISIS] because I smoked. Another child tried to persuade him with knowledge [not to], but he said he would register a complaint and commit a suicide bombing. An 11-year-old child was imagining himself as a soldier and a fighter.[82]

Echoing this, a male civil council member who was abducted and tortured by ISIS for 12 days stated:

[ISIS] abhorred all different ideas that did not fit their ideology. They persistently targeted education and intentionally sought to destroy the curriculum to control the new generation. They fought education, the Christian religion, even Islam. They hated everything that did not correspond to their cruel and dark ideas.[83]

This push to adopt ISIS’ ideological agenda was a driving force for those who created the ISIS curriculum.

Textbook reforms and curriculum developers

ISIS utilized various forms of propaganda and psychological manipulation within its curriculum to cement its ideology in the minds of its followers. Textbooks, teaching materials and multimedia resources were carefully crafted to evoke strong emotions, create a sense of superiority, and demonize those falling outside their worldview.[84]

The textbooks and learning materials developed by ISIS eradicated elements of traditional culture and history deemed un-Islamic by the group.[85] Through vivid imagery, symbols and language, ISIS sought to shape the perceptions and attitudes of students. Figures 3, 4 and 5 (below) depict the use of weaponry and military objects in the English for Islamic State textbook taught to foreign students.[86] A former kindergarten teacher from Hajin in Deir Ezzor shared an emotional testimony on the drastic textbook changes:

For example, in mathematics, instead of “1+1=2,” we had “one warplane + another warplane = two warplanes.” Their textbooks [went] against human nature.

There were other examples that advocated killing and murder. These textbooks ran contrary to the age-group of the kids. I found myself [in a difficult place]. I [could] either endanger myself or sacrifice my work.

So, I devised a scheme: I told teachers that on the surface we could pretend we were teaching their textbooks, but in reality, we would [avoid] the textbooks. Had we taught their textbooks, we would have produced monsters.[87]

For some non-religious subjects that existed in the pre-ISIS curriculum, teachers reported that they were promised textbooks that never materialised. A female teacher from Deir Ezzor recounted how after she had repeatedly asked about certain subjects: “They replied they were being printed and they would be delivered when they were ready. Actually, there were none.”[88]

Those who developed ISIS’ curriculum came from a range of countries, further adding to the complexity of ISIS’ overhauled education system.[90] To illustrate this, a male education official said that in Deir Ezzor, “the vast majority of ISIS members [were] from Iraq” alongside “Tunisians, Moroccans, Saudis and other Asian nationalities.” He also estimated that as many as 75% of ISIS members in Hajin were Iraqi, 10% were from Deir Ezzor province itself while the remainder came from Arab countries, Europe or Asia.[91]

Together, these individuals from various parts of the world created an ISIS curriculum that reflected the systematic and calculated nature of the group’s strategy. This was especially reflected in the new textbooks created by committees composed of foreigners. A male former teacher from Deir Ezzor described how: “We believe that there had been figures and leaders from other countries that ordered such changes [to the curriculum] to take place.”[92] Meanwhile, a current teacher, also from Deir Ezzor, specified that the curriculum developers were “mostly from Gulf countries—Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in particular.”[93]

The mechanism and the speed by which these textbooks were developed, printed, and published (often within a year or less) suggested that an efficient and generously funded system was already in place.[94] At the same time, the inclusion of elements of Wahhabismadvocating global jihad and support for the radicalization of foreign Muslims strongly indicated the influence of systems of Wahhabi mudaris (schools) in shaping these educational materials.[95]

Historically, Wahhabi ideology recruited Muslims worldwide through educational channels, financing the constructions of mosques, schools and funding publications.[96] While the origin of Wahhabism is rooted in Saudi Arabia,[97] the extent of its influence in shaping ISIS’ new textbooks is debated and hard to prove.[98] This is in part due to how the export of Wahhabism abroad usually involves complex financial trails, making it difficult to trace its origins.[99]

The curriculum imposed by ISIS promoted intolerance, hatred and violence, and was designed to brainwash and radicalise those moving through the group’s education system. A female teacher from Manbij reflected on the ISIS curriculum and its connection to Islamic ideology, stating that:

The curriculum employed by [ISIS] was a dominating, despotic one, that sought only to serve its ends and inculcate its ideology in the kid’s brains for two main goals: to keep them ignorant and to easily [motivate] them to serve its agenda.

She further suggested that the new curriculum, while upheld by ISIS as being oriented around the Quran, was “in direct contradiction with the basic tenets of Islam”:

This could be juxtaposed with the words of the Muslim scholar and reformer Abdul Rahman al-Kawakbi who says, “The despotic state not only denies people the right to live in divinity; rather, it strives to keep them ignorant. The worst kind of tyranny is that of ignorance. Tyrants seek to emasculate basic knowledge, the [one thing] that [could] contribute to the development or advancement of society.”[100]

Another male teacher agreed with the long-term plan of this agenda stating, that “ISIS targeted young people to instil its ideology into their minds,” reflecting a “systematic policy adopted by the group.”[101] Such extremist teachings had long-lasting effects on society—but especially on students.

Students and learning spaces

Learning while young is like carving in stone” (Rhyming saying in Arabic).[102]

ISIS drastically changed the educational landscape for students in northeast Syria. While ISIS was in power, students were denied their right to quality education and exposed to violence and fear. This section presents the voices of teachers, education officials and other affected individuals who have worked in education in northeast Syria. Three key themes related to students emerged from the desk review, interviews and focus group sessions: 1) school attendance disruptions; 2) gender; and 3) learning spaces.

School attendance disruptions

Under ISIS, the curriculum underwent extensive changes, negatively impacting student learning, but its impact on school attendance was also significant. One teacher interviewed estimated that under ISIS, 90% of students in Deir Ezzor governorate dropped out of school.[103] Various factors contributed to the disruption of school attendance, including the displacement of families, the loss of children’s lives, the physical destruction of schools, and the recruitment of children as fighters.

While ISIS’ rule over northeast Syria reduced school attendance rates in the region, schools under ISIS did not provide the quality, safe learning spaces to which children are entitled through international humanitarian law and conventions such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.[104] As such, schools themselves were danger zones for students, explaining why many parents chose to keep their children at home. The lack of safety at schools represents one of many reasons why students did not attend school during ISIS’ rule, in addition to those considered in the table below:

Range of factors preventing children from attending school under ISIS rule

| Family displacement | ISIS’ invasion forced many to flee their homes, with many seeking shelter in overcrowded camps.[105] Interviewees noted how families with the financial means and education often left to find peace and economic stability elsewhere.[106] Internal displacements resulted in significant disruptions to schooling, with many children unable to attend school due to the lack of facilities or the distance from their new homes. |

| School closures | ISIS was responsible for directly closing schools. For example, in 2015, an estimated 670,000 children in Aleppo, Deir Ezzor and Raqqa provinces were impacted when schools were closed while the ISIS curriculum was under development.[107] |

| Attendance issues | Under ISIS, many parents were afraid to send their children to school and would, as such, keep them home, although at times they were forced to send them.[108] One focus group participant in Raqqa shared that they kept their children “at home to ensure their safety.”[109] A teacher from Deir Ezzor governorate meanwhile described in an interview how there was also fear of sending children to school as “ISIS used to ask about family issues” and that this “incited fear among people as innocent children could reveal what was said about ISIS [at home]” and put their parents at risk of arrest or execution in the process.[110] |

| Death and injury | While ISIS was in power, there were cases of students being killed while at school. In 2014 alone, UNICEF reported that at least 160 children were killed and 343 wounded in attacks on schools in Syria, although this was probably under-estimated due to difficulties documenting and accessing data.[111] The use of schools for military purposes was highlighted during focus group sessions; one participant stated, “I was shot in my hands while going to my job in the bakery by an ISIS sniper positioned above a school.”[112] |

| Damage to school infrastructure | The conflict with ISIS resulted in damage to school infrastructure, with many schools damaged or destroyed in the fighting. [113] When school infrastructure was destroyed, students could not attend school. In some cases, ISIS targeted schools and universities, using them as weapons storage facilities and making them targets for airstrikes. In Kobane, which was never under full ISIS control, schools were closed for at least two years due to a variety of factors, including destruction and damage to school buildings.[114] |

| Child soldiers | Under ISIS, children were also recruited to serve as soldiers and fighters, depriving them of their right to education and exposing them to violence, trauma and, in some instances, death.[115] In 2016 alone, the UN recorded 274 cases of child soldier recruitment attributed to ISIS.[116] One researcher found that ISIS trained hundreds, if not thousands of children, for military engagement between 2014 and 2018.[117] |

| Gender | ISIS prohibited mixing of sexes among students, separating boys from girls starting from Grade 1.[118] Due to a shortage of schools, with many damaged from the conflict, classes were often on a limited schedule and alternative days were assigned for each gender.[119] As students got older, female students left school more often than boys in higher grades.[120] |

Often, these factors intersected with others to disrupt education altogether for students in northeast Syria. For example, one focus group participant from Kobane stated: “Our houses were destroyed, many children were orphaned, and many children dropped out of schools. During the war for Kobane, schools were closed in 2014. Schools were suspended, and our children were out of school for a long time.”[121]

A fear of miseducation, bombings and arrests further prevented students from attending schools and universities and left them confined to their homes.[122] A mother of six from Raqqa shared why she stopped sending her children to school:

[Beforehand,] my six children were excelling in school, and the level of education was good. However, when [ISIS] came, they turned schools into their headquarters, and I immediately stopped [sending] my children. They became an uneducated and completely ignorant generation. I didn’t send them to mosques out of fear that they would be influenced by [ISIS’ ideas].[123]

A participant in Raqqa, meanwhile, shared the story of their brother, who had to leave his university in Deir Ezzor due to the risk of being arrested by ISIS because he was studying in a government-controlled area.[124]

The box below details how life changed for students under ISIS from the perspective of a teacher from Manbij.

| Through the eyes of a teacher: Violations against children under ISIS During an interview, a female teacher in northeast Syria described the situation for students under ISIS in her region, Manbij, which was once considered a hub for scientific knowledge and education before the conflict. As a teacher since 2007, she witnessed the drastic changes that came with the ISIS rule: “In Manbij, hundreds of schools remained closed over a period of two years. Nearly 78,000 students were deprived of their right to education. Schools were renamed after Islamic symbols. Black banners were hoisted over the schools.” Students who attended these revamped institutions often witnessed or experienced lashings, beatings and other distressing acts of violence committed in public squares. Reflecting on her students, she remorsefully noted how “their childhood has been scarred. There are cases where children witnessed the beheading of their own fathers.” While some students could be accompanied by mothers to protect them inside the schools, they were still afraid and risked ISIS retaliating with violence or threats of death. This teacher also explained that of the children that were still in school, ISIS forced nearly half of all 12-year-old students, who were supposed to be in Grade 6, to move back to Grade 1 to re-educate them. Alongside this, school-aged children in Manbij were used and trained for combat missions, in violation of international humanitarian law. Sharing a specific example of hardship, the teacher described how on 27 July 2016, ISIS committed a massacre, killing IDPs Deir Hafir in Aleppo who had been living in one of the schools in Buhayr village in Manbij. Several of those who were killed in this massacre had relatives who were university students in other cities like Damascus, Homs and Latakia. The students were not allowed back home, separating them from their families and thus resulting in additional psychological trauma. [125] |

The loss of safe and quality education and the transformation of schools into ISIS headquarters had a profound impact on the lives of students. One focus group participant from Manbij expressed their frustration:

We were students at a school. The first step was the cessation of education, and everything we planned for was destroyed. We lost our childhood. Schools became their headquarters.

The first frustration was the loss of school. Our games, like football and simple things, turned into games involving firearms and weapon-like objects. We lived in a period of constant horror. Our schools remained closed, and the curriculum taught by ISIS included lessons on jihad. Their schools became mandatory, and they educated school children about mines and slaughter.[126]

While students encountered many challenges in accessing safe and quality education during ISIS rule, some of these were determined by the students’ gender.

Gender

On the surface, ISIS purported to offer the same education to boys and girls. A female former teacher from Deir Ezzor believed that “by teaching girls, ISIS sought to avert criticism [about] why it only focused on boys.”[127] In reality, though, ISIS assigned strict gender roles and restrictions through education, often treating boys and girls distinctly.

Many of the interviewees and focus group participants shared how boys and girls encountered these gender-assigned roles under ISIS. One male teacher from Deir Ezzor stated: “According to ISIS, men should be in the service of religion and present in all battles,[128] while women are supposed to stay at home and not work unless that serves religion.”[129] A female former teacher also from Deir Ezzor described that “girls had strict rules regarding dress, which was all black.”[130]

A man who used to be a student in Tal Brak in Hasakeh shared that girls who wanted an education often had to rely on volunteer teachers who provided instruction at home.[131] This gender inequality was also expressed by a male teacher from Tal Brak:

There was no equality between the two sexes […] as men were given precedence over women, who suffered abuse and injustice during the two years of ISIS rule we endured. This was obvious to everyone.[132]

These gender roles conflicted with the belief systems of many within local communities, with one male former teacher from Sarrin describing it as “terrorism” while highlighting that ISIS ignored the rights and roles of women in contradiction to the actual teachings of Islam.[133] As noted earlier, ISIS did not allow for gender mixing starting from Grade 1 onwards: that is, the first year of primary education around the age of six and seven.[134] According to a male teacher from Tal Brak, the segregation of classes for older children harmed students psychologically and prevented them from learning from one another.[135] Both men and women were not allowed to attend higher education institutions in government-controlled areas.[136]

While in theory ISIS allowed for equal access to its schools,[137] dropout rates among female students increased as students progressed to higher grades and were higher than dropout rates among male students. These higher dropout rates were partly attributed to Sadda Sayyam, ISIS’ top education official, who encouraged female students to marry ISIS foreign fighters.[138] One parent from Raqqa shared their daughter’s story of being a student under ISIS and how their sister had abandoned education for marriage:

My daughter, during the time of ISIS, was in first grade and was not allowed to receive an education. Now she is older and illiterate; she can neither read nor write because ISIS used to teach children to carry weapons and practice [“sexual jihad”]. They would forcibly marry girls they liked, disregarding their families’ wishes. My sister abandoned her education because [a family member] who was an emir in ISIS, forced her to quit her studies and married her off to several foreign men.[139]

As a result, parents would withdraw their daughters from school to prevent early marriages.[140]However, other parents would still encourage their children’s education, including daughters, to receive higher education in parts of the country not under ISIS control.

A participant shared that “ISIS used to harass female education exclusively, and we used to send them with difficulty to [Syrian] regime-controlled areas where universities were located.”[141] Another shared the burden of women and girls requiring a guardian (mahram) to travel. The father stated:

My daughter was studying in 12th grade […] in Homs. She couldn’t go alone to continue her studies because they required a guardian who was a first-degree relative to accompany her. I had to send her mother with her, which increased the costs.[142]

Learning spaces

ISIS’ rule over northeast Syria contributed to the destruction and closure of learning spaces and schools. While data on the exact number of schools destroyed and closed is unavailable, the Assistance Coordination Unit (ACU), a Syrian relief organisation, estimated in November 2016 that 1,378 out of 3,373 (41%) public schools surveyed in Syria ‘were not functioning.’ Similarly, a World Bank report published in July 2017 found that 53% of schools and universities were partially destroyed, while 10% were completely destroyed. Many of these learning spaces (40%) were in ISIS-controlled regions such as Raqqa.

More recent data, shown in the table below, gives a detailed picture of the extent of destruction of educational infrastructure in northeast Syria. In addition, it shows the regional variations of impact across different areas, with 50 out of 386 (13%) schools completely destroyed in Raqqa compared with four out of 346 (1%) in Manbij.

During the course of ISIS rule and the anti-ISIS conflict to oust the group, schools were often used as ‘detention centres, military bases, and sniper posts’ by ISIS, the Syrian government and non-state actors, further adding to the cost to the education sector.[143] Given their placement in conflict zones, attacks on schools also led to the killing and injury of hundreds of teachers and students, putting them at risk at school or en route to and from school each day.

The operational and physical state of schools in northeast Syria as of April 2023

| Area in northeast Syria | Operating | Completely destroyed | Partially destroyed | Repaired |

| Raqqa | 386 | 50 | 61 | 10 (still under repair) |

| Euphrates Region, including Kobane | 571 | 22 | 3 | 28 |

| Deir Ezzor | 739 | 86 | 165 | 0 |

| al-Jazeera Region | 1,773 | 30 | 18 | 6 |

| Manbij | 346 | 4 | 1 | 0 |

| Tabqa | 240 | 12 | 24 | 24 |

Source: Anonymous official in northeast Syria.[144]

Reflecting on these atrocities, a male former teacher from Deir Ezzor said:

During ISIS rule, schools were not safe. Anything could happen at any moment. ISIS turned most schools into training barracks or residences for its members. This made locals refrain from sending their children to school. How could people send their kids to be taught by an enemy? What do you expect ISIS to teach them?[145]

He further added that while there were local initiatives to rebuild schools to reopen them, future educational prospects are still unclear in areas that witnessed elevated levels of damage and destruction.[146]

According to a female teacher from Deir Ezzor, schools under ISIS “never felt safe” because “every day, you could see hisba members enter the classrooms fully armed. This caused fears among the kids. Hisba members were very arrogant, repressive, and imposing.”[147]

Another former teacher from Tal Brak added that while it is well-known that schools were used by different state and non-state actors as military barracks, ISIS went further and converted some schools into “slaughterhouses.”[148]

Curriculum and textbooks

[ISIS] did not keep any former book or subject.[63]

The curriculum played a pivotal role in ISIS’ strategic agenda, serving as an instrument for indoctrination and the dissemination of the group’s extremist ideology. Prior to ISIS’ presence in the region, the Syrian government’s curriculum was widespread throughout northeast Syria.

A Christian male civil council member shared how, in his area of al-Qahtaniyah:

The Syrian education system was very good. All Syrians [from different backgrounds] agree on this issue. Kurdish, Arab and Syrian students attended these schools and got a wonderful education.[64]

Another male teacher from Hasakeh agreed, stating:

All Syrians, regardless of their [religious or ethnic] backgrounds were in the same classes. No preference was given to one over the other. Words like Kurds or Arab [in the context of school curricula] were not used.[65]

Contrary to these views, Kurdish journalist Sardar Mlla Darwish, in an article on the state of education for Kurds in northeast Syria, noted that for decades prior to ISIS, ‘Syrian Kurds have endured a ban on speaking and studying in their mother tongue as a result of political pressure and repression from the Syrian regime.’[66] The Kurdish Project similarly reported that under the Syrian government, ‘Syrian Kurds were not allowed to use the Kurdish language, were not allowed to register babies with Kurdish names, were not allowed to attend private Kurdish schools, and were banned from publishing books or other written materials in Kurdish,’[67] leaving Kurds with limited access to an education if they were unwilling or unable to learn in Arabic.

However, with the arrival of ISIS, the government’s curriculum in general was abolished.[68] ISIS textbooks and instructional materials were systematically infused with propaganda and ideological messaging, reflecting the group’s radical interpretation of Islam. Notably, the curriculum was heavily militarised, with a primary focus on training young individuals to become active fighters in the group’s ranks.[69]

Through the analysis of collected data, two prominent sub-themes related to the curriculum and textbooks emerged: a) ideology and the militarisation of pedagogy; and b) textbook reforms and curriculum developers. These sub-themes shed light on the fundamental aspects of the curriculum reforms under ISIS rule, which in turn provide valuable insights into the group’s systematic manipulation of education for ideological purposes.

Ideology and the militarisation of pedagogy

In introducing its own highly ideological curriculum, ISIS overhauled the diverse range of subjects that once formed the basis of the Syrian curriculum. Music, physical education, nationalism, law and philosophy were among the subjects banned by ISIS in their efforts to reshape educational curricula within schools and universities.[70] This process of overhauling the curriculum was carried out in stages, as described by a male education official from Deir Ezzor:

When ISIS ordered schools to be reopened, it initially eliminated core subjects with the exception of mathematics and reading. This transitional phase lasted for approximately four months, during which time the existing curriculum was annulled. Subsequently, a new curriculum was introduced, accompanied by newly printed textbooks that were distributed to schools. The [new] ISIS curriculum included subjects such as reading, [mathematics], Islamic education and Quranic studies, which were taught in the initial stages. Later, subjects such as jurisprudence, creed, Quranic interpretation [tafsir] and traditions were introduced for higher stages.[71]

Furthermore, the curriculum focused on religious studies, including memorisation of the Quran, hadith and other Islamic texts, while also promoting extremist views about violence, jihad and the establishment of an Islamic state. One focus group session participant explained:

[ISIS] tried to manipulate children using all means possible, and they succeeded. If you wanted to work in the field of education, it had to be done secretly out of fear of them. The goal was to brainwash children.[72]

The impact of ISIS’ curriculum extended beyond the restructuring of subjects. Education became a domain for exclusively promoting the group’s interests, revolving around concepts of jihadand paradise.[73]The curriculum was also a recruiting tool that targeted unemployed youth with promises of material possessions, power, and leadership positions.[74] The indoctrination process was pervasive, aiming to mould the minds of individuals and instil a distorted understanding of Islam. ISIS’ curriculum actively propagated violence, advocating for armed conflict and endorsing acts of terror.[75] A male teacher from Tabqa explained this by stating: “They changed the textbooks to be able to insert their ideology into the minds of children. The aim was to recruit the kids as the ‘Cubs of the Caliphate’.”[76]

As such, ISIS placed a particular strategic emphasis on primary schooling as an entry point for disseminating their interpretation of Islam.[77] Educational standards were notably low, with mathematics stripped down and subjects such as physics and chemistry later banned.[78] Figure 1 and Figure 2 demonstrate the kind of Islamic textbooks introduced by ISIS in these early stages.[79] The titles of the books alone show that the focus of education was largely on the significance of the ”caliphate” and Islam.

ISIS used the militarisation of pedagogy, which can be defined as incorporating military themes and practices into the education system, to instil its values among youth in northeast Syria.[80] This included the use of military-style uniforms and disciplinary systems.[81] ISIS even offered classes and programmes that were designed to prepare students for combat, with recruiters invited to speak with students and promote careers in their battalions. Violence and aggression were regularly hailed as a means of problem-solving within ISIS pedagogy, as was the marginalisation of alternative views and value systems. Elaborating on this, a former school owner explained how:

They did not allow us to open private schools. I remember when I used to smoke, one of the children told me that he would report me to “the brothers” [ISIS] because I smoked. Another child tried to persuade him with knowledge [not to], but he said he would register a complaint and commit a suicide bombing. An 11-year-old child was imagining himself as a soldier and a fighter.[82]

Echoing this, a male civil council member who was abducted and tortured by ISIS for 12 days stated:

[ISIS] abhorred all different ideas that did not fit their ideology. They persistently targeted education and intentionally sought to destroy the curriculum to control the new generation. They fought education, the Christian religion, even Islam. They hated everything that did not correspond to their cruel and dark ideas.[83]

This push to adopt ISIS’ ideological agenda was a driving force for those who created the ISIS curriculum.

Textbook reforms and curriculum developers

ISIS utilized various forms of propaganda and psychological manipulation within its curriculum to cement its ideology in the minds of its followers. Textbooks, teaching materials and multimedia resources were carefully crafted to evoke strong emotions, create a sense of superiority, and demonize those falling outside their worldview.[84]

The textbooks and learning materials developed by ISIS eradicated elements of traditional culture and history deemed un-Islamic by the group.[85] Through vivid imagery, symbols and language, ISIS sought to shape the perceptions and attitudes of students. Figures 3, 4 and 5 (below) depict the use of weaponry and military objects in the English for Islamic State textbook taught to foreign students.[86] A former kindergarten teacher from Hajin in Deir Ezzor shared an emotional testimony on the drastic textbook changes:

For example, in mathematics, instead of “1+1=2,” we had “one warplane + another warplane = two warplanes.” Their textbooks [went] against human nature.

There were other examples that advocated killing and murder. These textbooks ran contrary to the age-group of the kids. I found myself [in a difficult place]. I [could] either endanger myself or sacrifice my work.

So, I devised a scheme: I told teachers that on the surface we could pretend we were teaching their textbooks, but in reality, we would [avoid] the textbooks. Had we taught their textbooks, we would have produced monsters.[87]

For some non-religious subjects that existed in the pre-ISIS curriculum, teachers reported that they were promised textbooks that never materialised. A female teacher from Deir Ezzor recounted how after she had repeatedly asked about certain subjects: “They replied they were being printed and they would be delivered when they were ready. Actually, there were none.”[88]

Those who developed ISIS’ curriculum came from a range of countries, further adding to the complexity of ISIS’ overhauled education system.[90] To illustrate this, a male education official said that in Deir Ezzor, “the vast majority of ISIS members [were] from Iraq” alongside “Tunisians, Moroccans, Saudis and other Asian nationalities.” He also estimated that as many as 75% of ISIS members in Hajin were Iraqi, 10% were from Deir Ezzor province itself while the remainder came from Arab countries, Europe or Asia.[91]

Together, these individuals from various parts of the world created an ISIS curriculum that reflected the systematic and calculated nature of the group’s strategy. This was especially reflected in the new textbooks created by committees composed of foreigners. A male former teacher from Deir Ezzor described how: “We believe that there had been figures and leaders from other countries that ordered such changes [to the curriculum] to take place.”[92] Meanwhile, a current teacher, also from Deir Ezzor, specified that the curriculum developers were “mostly from Gulf countries—Saudi Arabia and Kuwait in particular.”[93]

The mechanism and the speed by which these textbooks were developed, printed, and published (often within a year or less) suggested that an efficient and generously funded system was already in place.[94] At the same time, the inclusion of elements of Wahhabismadvocating global jihad and support for the radicalization of foreign Muslims strongly indicated the influence of systems of Wahhabi mudaris (schools) in shaping these educational materials.[95]

Historically, Wahhabi ideology recruited Muslims worldwide through educational channels, financing the constructions of mosques, schools and funding publications.[96] While the origin of Wahhabism is rooted in Saudi Arabia,[97] the extent of its influence in shaping ISIS’ new textbooks is debated and hard to prove.[98] This is in part due to how the export of Wahhabism abroad usually involves complex financial trails, making it difficult to trace its origins.[99]

The curriculum imposed by ISIS promoted intolerance, hatred and violence, and was designed to brainwash and radicalise those moving through the group’s education system. A female teacher from Manbij reflected on the ISIS curriculum and its connection to Islamic ideology, stating that:

The curriculum employed by [ISIS] was a dominating, despotic one, that sought only to serve its ends and inculcate its ideology in the kid’s brains for two main goals: to keep them ignorant and to easily [motivate] them to serve its agenda.

She further suggested that the new curriculum, while upheld by ISIS as being oriented around the Quran, was “in direct contradiction with the basic tenets of Islam”:

This could be juxtaposed with the words of the Muslim scholar and reformer Abdul Rahman al-Kawakbi who says, “The despotic state not only denies people the right to live in divinity; rather, it strives to keep them ignorant. The worst kind of tyranny is that of ignorance. Tyrants seek to emasculate basic knowledge, the [one thing] that [could] contribute to the development or advancement of society.”[100]

Another male teacher agreed with the long-term plan of this agenda stating, that “ISIS targeted young people to instil its ideology into their minds,” reflecting a “systematic policy adopted by the group.”[101] Such extremist teachings had long-lasting effects on society—but especially on students.

Students and learning spaces

Learning while young is like carving in stone” (Rhyming saying in Arabic).[102]

ISIS drastically changed the educational landscape for students in northeast Syria. While ISIS was in power, students were denied their right to quality education and exposed to violence and fear. This section presents the voices of teachers, education officials and other affected individuals who have worked in education in northeast Syria. Three key themes related to students emerged from the desk review, interviews and focus group sessions: 1) school attendance disruptions; 2) gender; and 3) learning spaces.

School attendance disruptions

Under ISIS, the curriculum underwent extensive changes, negatively impacting student learning, but its impact on school attendance was also significant. One teacher interviewed estimated that under ISIS, 90% of students in Deir Ezzor governorate dropped out of school.[103] Various factors contributed to the disruption of school attendance, including the displacement of families, the loss of children’s lives, the physical destruction of schools, and the recruitment of children as fighters.

While ISIS’ rule over northeast Syria reduced school attendance rates in the region, schools under ISIS did not provide the quality, safe learning spaces to which children are entitled through international humanitarian law and conventions such as the UN Convention on the Rights of the Child.[104] As such, schools themselves were danger zones for students, explaining why many parents chose to keep their children at home. The lack of safety at schools represents one of many reasons why students did not attend school during ISIS’ rule, in addition to those considered in the table below:

Range of factors preventing children from attending school under ISIS rule

| Family displacement | ISIS’ invasion forced many to flee their homes, with many seeking shelter in overcrowded camps.[105] Interviewees noted how families with the financial means and education often left to find peace and economic stability elsewhere.[106] Internal displacements resulted in significant disruptions to schooling, with many children unable to attend school due to the lack of facilities or the distance from their new homes. |

| School closures | ISIS was responsible for directly closing schools. For example, in 2015, an estimated 670,000 children in Aleppo, Deir Ezzor and Raqqa provinces were impacted when schools were closed while the ISIS curriculum was under development.[107] |

| Attendance issues | Under ISIS, many parents were afraid to send their children to school and would, as such, keep them home, although at times they were forced to send them.[108] One focus group participant in Raqqa shared that they kept their children “at home to ensure their safety.”[109] A teacher from Deir Ezzor governorate meanwhile described in an interview how there was also fear of sending children to school as “ISIS used to ask about family issues” and that this “incited fear among people as innocent children could reveal what was said about ISIS [at home]” and put their parents at risk of arrest or execution in the process.[110] |

| Death and injury | While ISIS was in power, there were cases of students being killed while at school. In 2014 alone, UNICEF reported that at least 160 children were killed and 343 wounded in attacks on schools in Syria, although this was probably under-estimated due to difficulties documenting and accessing data.[111] The use of schools for military purposes was highlighted during focus group sessions; one participant stated, “I was shot in my hands while going to my job in the bakery by an ISIS sniper positioned above a school.”[112] |

| Damage to school infrastructure | The conflict with ISIS resulted in damage to school infrastructure, with many schools damaged or destroyed in the fighting. [113] When school infrastructure was destroyed, students could not attend school. In some cases, ISIS targeted schools and universities, using them as weapons storage facilities and making them targets for airstrikes. In Kobane, which was never under full ISIS control, schools were closed for at least two years due to a variety of factors, including destruction and damage to school buildings.[114] |

| Child soldiers | Under ISIS, children were also recruited to serve as soldiers and fighters, depriving them of their right to education and exposing them to violence, trauma and, in some instances, death.[115] In 2016 alone, the UN recorded 274 cases of child soldier recruitment attributed to ISIS.[116] One researcher found that ISIS trained hundreds, if not thousands of children, for military engagement between 2014 and 2018.[117] |

| Gender | ISIS prohibited mixing of sexes among students, separating boys from girls starting from Grade 1.[118] Due to a shortage of schools, with many damaged from the conflict, classes were often on a limited schedule and alternative days were assigned for each gender.[119] As students got older, female students left school more often than boys in higher grades.[120] |

Often, these factors intersected with others to disrupt education altogether for students in northeast Syria. For example, one focus group participant from Kobane stated: “Our houses were destroyed, many children were orphaned, and many children dropped out of schools. During the war for Kobane, schools were closed in 2014. Schools were suspended, and our children were out of school for a long time.”[121]

A fear of miseducation, bombings and arrests further prevented students from attending schools and universities and left them confined to their homes.[122] A mother of six from Raqqa shared why she stopped sending her children to school:

[Beforehand,] my six children were excelling in school, and the level of education was good. However, when [ISIS] came, they turned schools into their headquarters, and I immediately stopped [sending] my children. They became an uneducated and completely ignorant generation. I didn’t send them to mosques out of fear that they would be influenced by [ISIS’ ideas].[123]

A participant in Raqqa, meanwhile, shared the story of their brother, who had to leave his university in Deir Ezzor due to the risk of being arrested by ISIS because he was studying in a government-controlled area.[124]

The box below details how life changed for students under ISIS from the perspective of a teacher from Manbij.

| Through the eyes of a teacher: Violations against children under ISIS During an interview, a female teacher in northeast Syria described the situation for students under ISIS in her region, Manbij, which was once considered a hub for scientific knowledge and education before the conflict. As a teacher since 2007, she witnessed the drastic changes that came with the ISIS rule: “In Manbij, hundreds of schools remained closed over a period of two years. Nearly 78,000 students were deprived of their right to education. Schools were renamed after Islamic symbols. Black banners were hoisted over the schools.” Students who attended these revamped institutions often witnessed or experienced lashings, beatings and other distressing acts of violence committed in public squares. Reflecting on her students, she remorsefully noted how “their childhood has been scarred. There are cases where children witnessed the beheading of their own fathers.” While some students could be accompanied by mothers to protect them inside the schools, they were still afraid and risked ISIS retaliating with violence or threats of death. This teacher also explained that of the children that were still in school, ISIS forced nearly half of all 12-year-old students, who were supposed to be in Grade 6, to move back to Grade 1 to re-educate them. Alongside this, school-aged children in Manbij were used and trained for combat missions, in violation of international humanitarian law. Sharing a specific example of hardship, the teacher described how on 27 July 2016, ISIS committed a massacre, killing IDPs Deir Hafir in Aleppo who had been living in one of the schools in Buhayr village in Manbij. Several of those who were killed in this massacre had relatives who were university students in other cities like Damascus, Homs and Latakia. The students were not allowed back home, separating them from their families and thus resulting in additional psychological trauma. [125] |

The loss of safe and quality education and the transformation of schools into ISIS headquarters had a profound impact on the lives of students. One focus group participant from Manbij expressed their frustration:

We were students at a school. The first step was the cessation of education, and everything we planned for was destroyed. We lost our childhood. Schools became their headquarters.

The first frustration was the loss of school. Our games, like football and simple things, turned into games involving firearms and weapon-like objects. We lived in a period of constant horror. Our schools remained closed, and the curriculum taught by ISIS included lessons on jihad. Their schools became mandatory, and they educated school children about mines and slaughter.[126]

While students encountered many challenges in accessing safe and quality education during ISIS rule, some of these were determined by the students’ gender.

Gender

On the surface, ISIS purported to offer the same education to boys and girls. A female former teacher from Deir Ezzor believed that “by teaching girls, ISIS sought to avert criticism [about] why it only focused on boys.”[127] In reality, though, ISIS assigned strict gender roles and restrictions through education, often treating boys and girls distinctly.

Many of the interviewees and focus group participants shared how boys and girls encountered these gender-assigned roles under ISIS. One male teacher from Deir Ezzor stated: “According to ISIS, men should be in the service of religion and present in all battles,[128] while women are supposed to stay at home and not work unless that serves religion.”[129] A female former teacher also from Deir Ezzor described that “girls had strict rules regarding dress, which was all black.”[130]

A man who used to be a student in Tal Brak in Hasakeh shared that girls who wanted an education often had to rely on volunteer teachers who provided instruction at home.[131] This gender inequality was also expressed by a male teacher from Tal Brak:

There was no equality between the two sexes […] as men were given precedence over women, who suffered abuse and injustice during the two years of ISIS rule we endured. This was obvious to everyone.[132]