It was in Deir Ezzor that ISIS made its final stand, having been expelled from all its former territories in northeast Syria and Iraq. It was therefore the place where the local population suffered longer than any other area—around six years in total—under ISIS control.

However, the group remains a potent threat in the area, something the research team encountered during research for this chapter. With ISIS sleeper cells still present, conducting research and interviews posed risks; as a result, many victims agreed only to be interviewed in the relative safety of their own homes, for fear of being targeted. Continued tribal conflicts in the area further contributed to instability: during one collective meeting to collect testimonies for this chapter, an inter-tribal gunfight broke out in the same district, killing six people.

Deir Ezzor before the conflict

Deir Ezzor governorate sits on the banks of the Euphrates River in northeast Syria. It is the country’s second-biggest province after Homs, covering almost a fifth of Syria’s total territory. The Euphrates diagonally bisects the province: on the western banks of the river lies the Syrian desert of al-Sham, also known as Shamiyyah, whereas to the northeast lies al-Jazeera, “the island” connecting the provinces of Deir Ezzor and Hasakeh.[1] The region is divided into three districts: Deir Ezzor, al-Mayadeen and Albu Kamal.

Inhabited for millennia by a series of civilisations, including the third millennium BC Semitic city-state of Mari, the Hellenistic city of Dura-Europos and al-Basira, the area also has Roman and Byzantine ruins at Halabiye, on the eastern bank of the Euphrates.

The modern city of Deir Ezzor was founded in 1865 under the Ottoman Empire, which designated it as the sanjak, or administrative region, of the area. It soon emerged as a commercial centre on the caravanserai route between Aleppo and Baghdad, seeing rapid growth in the middle of the last century. Deir Ezzor itself boasts a late Ottoman covered market in its Old City, along with several places of worship: the Kushiya Church, the Church of the Virgin and the Hamidi Mosque, also built during the Ottoman era. Later, in 1921, France occupied Deir Ezzor as part of its Syrian mandate established under the Sykes-Picot and San Remo treaties.

Deir Ezzor has a relatively homogenous ethnic and sectarian make-up. Arabs make up most of its population, and its residents speak Arabic in a dialect close to that of Iraq, specifically the province of Anbar just across the border, where many of the Syrian clans in the area have family links. Arab tribes settled in the region during the 18th and 19th centuries and turned to agriculture, gradually coming to dominate the area in the decades that followed. Major rural tribes in Deir Ezzor included the Ageidat, al-Baggara and Bousaraya, as well as secondary tribes such as the Bakaan, Obeid, Jhaish, Abu Hardan, Marasma and Jaghayfah. In the three main cities of the governorate, other tribes are also found, such as the Kharshan, Zafir, Jweihsneh and Maamra tribes in Deir Ezzor; the Kalayeen in al-Mayadeen; and the Rawiyeen and Aniyyen in Albu Kamal.[2]

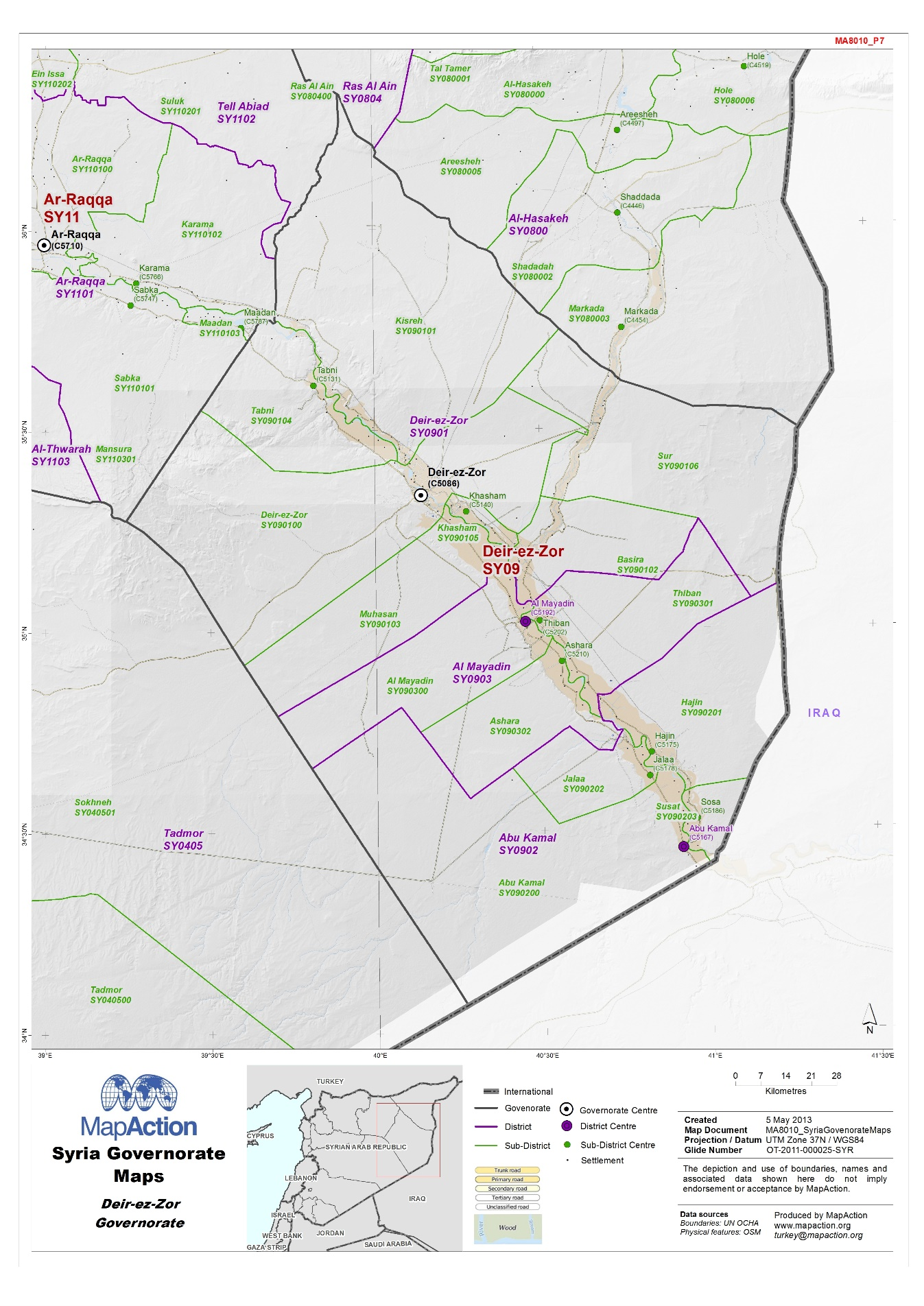

Figure 6: Deir Ezzor province.[3]

The remainder of Deir Ezzor’s population consists of Kurds, Armenians and small numbers of Turkmens, Assyrians and other Christians. The city also hosts several Syriac families. The Kurdish minority resides in the north of the province. Like the other areas of northeast Syria, Deir Ezzor served as a refuge for Armenians fleeing attack during the First World War when the then-mayor of Deir Ezzor, Haj Fadel al-Abboud, offered them protection.[4] In later decades, the Armenian Martyrs’ Church in Deir Ezzor city would become a destination for thousands of Armenian pilgrims, both inside and outside Syria, each year.

The Ottomans, and later the French, forced Deir Ezzor’s tribes to settle. While this effort disbanded tribal federations, it also increased the power of the tribal sheikhs over their members, who turned into landowners.[5] The economy became increasingly based on agricultural production and tax collection. In the following decades, under the French Mandate, Deir Ezzor saw some development, such as the construction of the suspension bridge that became a local landmark, as well as the founding of the city’s first bank in 1930, the establishment of a courthouse, a national library, the city museum and a municipal stadium, along with the introduction of electricity through the Euphrates Electricity Company. Nevertheless, there was a long struggle in Deir Ezzor against the French Mandate; Mohammed al-Ayesh, one of the anti-French uprising’s rebel leaders, would be imprisoned for 20 years.[6]

Following Syria’s independence in 1946, the province experienced demographic and economic development, resulting from the stable situation in the country. In 1958, when Syria had united with Egypt in the short-lived United Arab Republic, the Agrarian Reform Law (Law 317/1958) was passed. Land reform redistributed lands from the wealthy landowners to the peasants.[7] Deir Ezzor’s farming initially flourished due to the government’s support, which came in the form of loans, seeds, fertilisers, fodder and animal medicines; as a result, the tribal sheikhs, who had been the largest landowners, lost significant power. Their authority changed from political to social, and they became increasingly dependent on the Syrian state for access to privileges.[8]

Following the coup that brought Hafez al-Assad to power in 1970, dissatisfaction with the central authorities lingered.[9] Deir Ezzor was overlooked, and Damascus responded to expressions of discontent with divide-and-rule policies. On the one hand, there had been a tradition since before independence of reserving a ministerial post in various Syrian administrations for a member of the Deir Ezzor bourgeoisie. The former anti-French rebel, Mohammed al-Ayesh, had been the first in northeast Syria to become a government minister. Additionally, the Syrian state would enter strategic alliances, with key tribes in the area, who were in turn rewarded for their loyalty. Hafez al-Assad motivated tribal leaders to join the Ba’ath party and, in return, offered tribesmen positions in local administration—whether in local councils or as mukhtars and mayors.[10]

Besides these forms of tokenism and clientelism, the state exercised a monopoly on the exploitation of the region’s resources and installed loyalists in key positions in the oil sector as well as the army and civilian governance administration. Exploitation of Syria’s oil commenced in the 1960s. Gradually, its oil fields, including those in Deir Ezzor, were developed, with oil production peaking during the 1990s.[11] The development of the oil industry in Deir Ezzor drove the growth of the city and public services, and gave rise to more companies, both public and private. Over time, it attracted migrants and created job opportunities in the major oil and gas fields that were developed in the area, most prominently the al-Omar field, 15 kilometres east of the town of al-Busira and north of al-Mayadeen; the Conoco oil field and gas plant, east of Deir Ezzor city; and the oil fields of al-Tanak, al-Ward, al-Asbaa, al-Taym, al-Jafra, al-Tabia, al-Mahash and al-Nishan. The area was also home to mines, such as the al-Tebni rock salt mine, about 40 kilometres north of Deir Ezzor city.

But like the provinces of Raqqa and Hasakeh, Damascus saw Deir Ezzor primarily as a supplier of natural resources. Despite its oil wealth and plentiful freshwater reserves, Deir Ezzor did not see investment in large-scale development projects; for example, refinement of oil was done at the Banyias and Homs refineries close to the Syrian coast.

As a result, most people in Deir Ezzor lived humble, hard-working lives. There were modest industrial activities, mainly in the public sector, focused on food production and processing, but farming was the major source of livelihoods. With lands on both sides of the Euphrates highly fertile, wheat and cotton were the most productive crops in the region; some also farmed sesame, vegetables and certain fruit trees, including olives and pomegranates, while others kept livestock. The city also had a developed handicraft sector and a reputation for its high-quality and unique designs of silk, woven fabrics, ceramics, pottery, copper, jewellery, and wooden furniture.

Some would say the authorities regarded eastern Syrians as backward Bedouins; indeed, until Syria’s independence, Deir Ezzor had few schools and residents had access to few sources of education other than books. Few, if any political positions, went to people from Deir Ezzor, and relations with Damascus became increasingly securitised after Hafez al-Assad took power in 1970. While investment in infrastructure was lacking, a Syrian army special force was stationed in the province to impose security and prevent any “terrorist activities.” The new constitution of 1973 imposed the teaching of Ba’athist ideology at every level of education, and special privileges, such as priority in university admission processes, were reserved for party members. Political pluralism evaporated, and any independent political activity was met with arrests and severe repression.

To make matters worse, following years of drought in the 1980s, farmers in the country’s east were headed for ruin. Salt began seeping into large areas of farmland, due to the use of traditional irrigation methods and wasteful irrigation of crops. The government proved unable to offer effective solutions to this problem. In Deir Ezzor, these economic worries added to concerns over increasing political repression.

The Muslim Brotherhood, which had experienced significant growth in Syria and elsewhere in the Middle East, emerged in Deir Ezzor around the same time. It sought to capitalise on the discontent in the province. Brotherhood members attracted a large following and played a leading role in anti-government demonstrations, especially over the social and economic issues facing residents of Deir Ezzor. In 1982, during the Brotherhood-linked armed uprising in Hama, the government responded with a violent crackdown; although the violence was not at the same level of intensity as that in Hama or even Manbij, Brotherhood members in Deir Ezzor were arrested and disappeared into the regime’s infamous detention archipelago. This put an end to political life in the governorate for decades to come.

Assad’s policy of weakening the relationship between tribal members and their sheikhs in favour of their relationship to the state created dissent within tribes, between leaders and their tribesmen.[12] Neo-liberal reforms introduced after 2000 by Hafez’s son and successor, Bashar al-Assad, heightened these divisions and contradictions. The governorate had seen some development: according to the National Report on Human Development published by the presidency of the Syrian Council of Ministers in 2007, there were now 835 schools, and illiteracy had been reduced to only 4.1%. Nevertheless, it took until 2006 before the only university in the region—the state-funded Euphrates University—was established.[13] Only 2.1% of Deir Ezzor province’s population, totalling approximately one million people in the 2004 census,[14] had been educated to university level. Basic healthcare was available, and the region had nine public and 21 private hospitals; however, they often lacked personnel and supplies.

The economic difficulties led many of Deir Ezzor’s tribesmen to migrate to the Gulf. There, newfound jobs, and financial stability gave migrants economic independence outside of tribal structures. A new class of businessmen emerged in Deir Ezzor to rival traditional tribal authorities.[15] These growing rifts would later manifest during the popular uprisings in Deir Ezzor after 2011.

The other important development that would impact local conditions in Deir Ezzor in the run-up to the Syrian uprising and conflict was the US invasion of Iraq. Assad, fearful the US would extend its operations to Syria, had funnelled extremist fighters into Iraq.[16] Deir Ezzor, on the border with Iraq, therefore served as an important crossing point, and the area developed a strong Salafi-jihadi presence. Fighters who returned organised hardline cells that would later play a role in the formation of Jabhat al-Nusra and, subsequently, the entry of ISIS into the area.[17]

Reflecting on the time before the outbreak of the Syrian war, Deir Ezzor’s residents related their qualms with the lack of political freedom. “There were restrictions on what you could say and think. You could not talk about politics,” one interviewee said.[18]

Looking back, however, many missed the relative security and prosperity of that period compared to what would follow. “Salaries were low, but life was good. My family was simple and poor, but the security situation was stable,” said a teacher in a government school before the conflict.[19]

“When the Syrian regime was in control,” another Deir Ezzor resident added:

Life was stable. State employees had a good income, about $450 a month. Syria was calm and didn’t have any problems, although there were restrictions on freedom. Lots of things were banned, and freedom of expression was non-existent because of the security apparatus.[20]

Nonetheless, the people of Deir Ezzor, like many others across Syria, joined an uprising in the hope of a better future—but ended up experiencing a decade of violence and terror instead.

The conflict in Deir Ezzor

Unsurprisingly, Deir Ezzor was early to join the Syrian uprising. The first demonstration took place in March 2011, the same month as the uprising first began in Dera’a. By April 2011, many locals in Deir Ezzor had joined nationwide demonstrations calling for political change. The security services responded with excessive violence, using live fire in response to a demonstration that started outside Deir Ezzor city’s stadium.[21]

According to a detailed study of northeast Syria’s post-2011 tribal dynamics, some of Deir Ezzor’s tribesmen joined or supported the early protests—such as the sheikhs of the al-Baggara and Albu-Rahmah tribes[22]—however, most tribes took a more pragmatic or outwardly pro-regime stance at the beginning. Assad mobilised tribal sheikhs and pro-regime dignitaries to shore up support.[23] The regime also promised political reform if the tribes refrained from protesting. As a result, most tribal leaders remained neutral or pro-government; some tribes reportedly even supplied those loyal to the regime with weapons, such as the al-Hassan tribe in Albu Kamal.[24]

From the summer of 2011, government forces and pro-government militias took complete control over Deir Ezzor city and sought to suppress protesters with extreme force, killing at least 20 in August that year alone.[25] This accelerated the process of militarisation. Over the next months, several brigades emerged in the area, including the Ahfad al-Rasoul brigades, which relied heavily on financial support from the Gulf and was therefore able to operate independently from tribal networks.[26] There were fierce battles with government forces, which lost control over the city apart from a nearby airbase and a few neighbourhoods.

By August 2012, with Assad focused on Aleppo, the Syrian government gradually lost its dominance over Deir Ezzor city and the outlying countryside to the FSA and al-Qaida-linked fighters who had come in from Iraq.[27] One popular commander in Deir Ezzor at the time was Ismail al-Abdullah, later widely known as Abu Ishaq, who defected from the Syrian army and became a commander in Liwa‘ al-Ahwazi.[28] The defection of Assad’s prime minister, Riyad Farid Hijab, and his ambassador to Iraq, Nawaf al-Fares, both of whom had ties to Deir Ezzor’s tribes, served as another blow.[29]

Despite being in control over much of Deir Ezzor city and the countryside, the FSA failed to build a military structure strong enough to deter attacks on a local level. A chaotic situation ensued. Tribes established their own armed groups.[30] Public services were largely disrupted, either by the fighting or because Damascus cut off access.[31] Tribes also seized oil wells: the al-Shaitat tribe took the al-Tenek oil field, for example, and the al-Bkayyer tribe gained control of the Conoco plant, together with members of the AlBu Kamel tribe.[32] Some tribes worked with Jabhat al-Nusra to capture oil wells in exchange for granting Nusra a share in the profits: a prominent example was the Bu Chamel tribe, which conquered oil wells in al-Shuhayl as well as the al-Omar oil field with Nusra’s support.[33]

Many of Deir-Ezzor’s residents were impacted by the radical changes. “Lots of armed factions came, and each faction only cared about its own interests,”one man said, adding that:

There was looting and theft, and we had no safety. The economy tanked and agriculture struggled because there were no seeds anymore.

We had no security. The place was run by armed gangs. Every gang looked after itself. There were no clinics or hospitals anymore, no medicines. Most doctors emigrated, and the situation got worse and worse. It was total chaos.[34]

Residents in other areas, however, found the situation more tolerable. “Our situation in Hajin was relatively comfortable,” one tribesman said, “because the armed factions in our area were formed by local men. Being in a tribal area, they tried not to interfere with people’s private lives.”[35]

By the end of 2012, government forces had withdrawn from the majority of Deir Ezzor, although the city would remain divided between regime- and opposition-held areas. The city’s suspension bridge had been destroyed by regime shelling, and only one bridge, which locals called the “bridge of death,” remained to connect the two sides.[36] Like elsewhere in Syria, around this time, Deir Ezzor’s rebel groups came to be increasingly dominated by Islamist forces backed by Gulf states. Sectarian atrocities followed: on 10 June 2013, 60 Shi’a men, women, and children, including at least 30 civilians, were killed in the town of Hatla in northeastern Deir Ezzor .[37] Afterwards, they raised a black flag and celebrated.

The arrival of ISIS

In their attempt to secure the governorate, Nusra formed the Mujahedin Shura Council, based in the town of al-Shuhayl in eastern Deir Ezzor. The formation included several factions: the al-Ikhlas Brigade, the Mu’tah Brigade (from the al-Shuhayl tribe), the Ibn al-Qayyim Brigade (from the al-Shaitat tribe), and the al-Qaaqaa Islamic Brigade.[38] When Nusra and ISIS separated in April 2013, many of Nusra’s foreign fighters joined ISIS; this, in turn, caused local tribes to join Nusra, as there were ”spots to fill.”[39]

Until then, ISIS had fought alongside the other opposition groups in battles for the Deir Ezzor airbase and the city’s security quarter, which allowed it to gradually establish a foothold in the region. Now, though, the group sought control of the entire province for itself. It capitalised on local communities’ religious sympathies but was also able to pay high salaries, which made it attractive to a population that had quickly fallen into extreme poverty.

Furthermore, it successfully played tribal politics against Nusra, which was perceived to be cooperating closely with the Bu Chamel tribe. [40] By September 2013, ISIS was strong enough to launch a blistering assault on Ahfad al-Rasoul, swiftly beating it, seizing its weapons and forcing its leadership to pledge allegiance to ISIS.[41] Nusra, together with Ahrar al-Sham and members of the al-Shaitat tribe, tried to take over the Conoco plant from the al-Ageidat. The al-Ageidat, for their part, sought ISIS support to fend off the attack.[42]

ISIS withdrew to the town of al-Shaddadah in Hasakeh, where it established a base of operations under the command of Abu Omar al-Shishani, later the group’s notorious “minister of war.” As it planned further operations against Nusra in Deir Ezzor, it built alliances with tribes that opposed Nusra, such as the al-Gu’ran tribe, who had held a grudge against Nusra following its attacks on oil wells.[43] Nevertheless, ISIS suffered various losses: Nusra and its allies managed to capture the Conoco gas plant, and parts of the Jadeed Ageidat area. By February 2014, the group was nearly pushed out of Deir Ezzor altogether.

The fall of al-Shuhayl

Eventually, over the next months, ISIS gained the upper hand over Nusra and its allies. There had, for example, been heavy fighting between Nusra and ISIS over the border town of Albu Kamal. In April 2014, 68 were killed in clashes, dozens of whom were from Nusra and its allies.[44] Slowly, ISIS chipped away at Nusra’s presence: first, in the western and northern countryside of Deir Ezzor before the group used weapons acquired in Mosul in early June 2014 to send a military convoy from Iraq across the border into Albu Kamal.[45] This force fired indiscriminately during the assault and placed snipers in tall buildings, killing both fighters and civilians in the streets. The battle continued for three days, leaving more than 85 civilians dead, including women and children. Albu Kamal fell to ISIS, which then proceeded towards al-Shuhayl.[46]

Al-Shuhayl was strategically and symbolically important. Nusra had established its base of operations in the town, but it was also the hometown of Abu Mariya al-Qahtani, Jabhat al-Nusra’s second-in-command. At one time, it was even rumoured to be the hometown of Nusra’s leader, Abu Muhammad al-Jolani.[47] Commanded by Shishani, ISIS besieged al-Shuhayl and bombed the town with heavy artillery installed in the nearby town of al-Basira. The shelling lasted for four days, during which at least 18 people were killed and more than 60 wounded, all of them civilians.

After several days, Nusra-affiliated fighters inside the town started running out of ammunition. They had received no outside help, despite issuing dozens of distress calls, and were left no option but to seek a deal with ISIS. In exchange for a ceasefire, ISIS demanded the fighters in the town pledge allegiance to it; it also agreed their fighters would not enter the city, the residents would not be displaced and the town’s fighters would be allowed to keep their weapons. The next day, ISIS changed its conditions, demanding that all residents leave and the remaining fighters hand over their weapons. Jabhat al-Nusra and Jaish al-Islam, as well as the other factions under the Mujahideen Shura Council, refused, choosing instead to withdraw, first to al-Mayadeen. From there, Nusra moved to the mountainous Qalamoun region to the west of Damascus as well as to southern Syria’s Dera’a; FSA factions moved northward. As a result, by mid-July 2014, ISIS was in control of nearly all of Deir Ezzor, apart from half of Deir Ezzor city, which remained under the control of pro-Assad forces.[48]

Deir Ezzor’s tribal politics influenced how ISIS controlled the towns that now came under its control. ISIS’ wali (governor) for Deir Ezzor was Amer al-Rafdan, from the al-Rafdan family of the al-Bkayyer tribe based in the Jadeed Ageidat area. Since the Rafdan family had been expelled by Nusra and the allied Bu Chamel tribe when ISIS took control of al-Shuhayl, Rafdan saw an opportunity to avenge the tribe’s humiliation. He issued a decision to displace al-Shuhayl’s inhabitants belonging to the Bu Chamel tribe for ten days.[49] Some 30,000 people were forced out, according to the UK-based Syrian Observatory for Human Rights,[50] and were only allowed to return after they declared their “repentance.”[51]

‘Take the head of your apostate son’: The massacre of the al-Shaitat tribe

The al-Shaitat clan, which includes residents of Abu Hamam town and the nearby villages of al-Kishkiyah and Gharanij, is a branch of the Ageidat tribe whose lands extend deep into Iraq. As ISIS had expanded across Deir Ezzor, the al-Shaitat allied with Nusra, putting up fierce resistance against ISIS.

When Nusra was expelled from Deir Ezzor, the al-Shaitat, now on the losing side, were left in a precarious position. Although ISIS made numerous promises of clemency to tribes across Deir Ezzor in this period, the agreement concluded over al-Shuhayl and the return of inhabitants following their repentance were not extended to the al-Shaitat. Nevertheless, initially, clan elders negotiated with ISIS that their fighters would hand over their weapons in exchange for undergoing Shari’a courses and “repentance” sessions.[52] According to Omar Abu Layla, an activist and former FSA spokesperson in the east of Syria, the agreement also covered the oil wells. Either way, ISIS had never intended to respect it.[53]

After some initial small confrontations between ISIS and al-Shaitat members, matters came to a head in August 2014. An ISIS patrol raided a home in Abu Hamam—which they were not allowed to do under the agreement—and killed the man they were searching for.[54] Al-Shaitat members from Abu Hamam killed several foreign fighters and burned ISIS’ local headquarters in response.[55] One witness reflected on what had happened:

An ISIS patrol from the al-Battar al-Libi battalion raided some houses in the area. They killed three people by cutting their throats. That sparked a battle between the two sides, which ended with the killing of all the ISIS members at their bases in the area.

The group then withdrew from our area and the surroundings, to come back and strike again more strongly. That’s what happened. They came back with a heavily armed convoy and lots of fighters.

There was a big battle and ISIS took heavy losses, due to the experience of some [local] fighters and their knowledge of the area. This made ISIS more and more angry, so it sent in reinforcements from several other regions, including some of its leaders, to supervise the fight. [56]

ISIS responded by detaining and then killing 50 al-Shaitat members working at the al-Tanak oilfield. Their bodies were buried in a mass grave, according to Abu Layla.[57] Outraged by the treatment of their fellow tribesmen, the incident led hundreds of al-Shaitat members to take up arms against ISIS. They killed several fighters and burned the group’s bases in Sweidan al-Jazeera and al-Tayyana. ISIS responded to the uprising with excessive force and treated the rebelling tribe with contempt. A member of the al-Shaitat clan recounted how ISIS killed his brothers during the clashes:

Someone told me that two young men had been killed close to our house. I ran unconsciously. When I arrived, I saw that their heads had been cut off. Blood was gushing out of them. I lost control of myself. I screamed: “They killed two of my brothers!”

I think [Y.] had been killed before [A.], because I saw his head separated from his body. I found their severed heads. I screamed and called out to my brothers: “There is no might and no power except with God.”

My third brother ran home and brought back a gun. He started running and shooting at the headquarters of the Chechens [foreign ISIS fighters], who fired back. I called him and told him: “Come back! They’ll kill you like they killed our brothers.”

Minutes later, he was hit by five bullets from their base. I was too scared to go on. Removing the bodies wasn’t allowed, but I carried them home anyway. When I arrived, my family and children started screaming from the sight.[58]

Using a fatwa, ISIS then labelled the al-Shaitat a “group that resists Islamic rule through force of arms,” stating that:

It is not permissible to conclude a truce with them, nor to release their captives, neither for money nor for any other purpose. It is not permissible to eat the meat of the animals they slaughter, and it is not permissible for anyone to marry their women. It is permitted to kill them as captives and to pursue and kill any one of them who escapes. It is also permitted to kill them when they are wounded. They must be fought, even if they do not start the fight.[59]

ISIS brought in reinforcements from Hasakeh and, on 5 August, laid siege to Abu Hamam. An al-Shaitat member who lived through the ordeal recalled what happened next:

After about 15 days of fighting, [ISIS] took control of the area, due to a suffocating siege, a lack of ammunition and medicines, and the number of wounded, as well as indiscriminate ISIS shelling of residential areas.

After the fighters left, ISIS moved in and carried out a series of killings, forced displacement and slaughter, despite promising to only target those who had fought it. This was totally untrue; they only killed unarmed civilians.

My family and I went to al-Shaafah and stayed in a school on 24th Street with my siblings and the people who had fled with us. Suddenly, a big ISIS patrol arrived and surrounded the school. Some fighters came inside. My father was with us.

They gathered the children and women in the school yard. One young fighter came forward and grabbed one of my brothers. He beat him in front of the women and children, then made him kneel, took out a knife from his sleeve and slaughtered him, in front of my father, the women and children. This was on 13 August 2014, between 7 and 8 am.

After cutting off my brother’s head, the fighter said, “God is great,” then threw [his head] in front of my father and said: “Take the head of your apostate son.”

The children started screaming and the women were crying from the horror of what they were seeing. But my father stayed silent. He didn’t say a single word.

Then the patrol arrested my siblings and their children. I managed to escape by jumping from the car. Some ISIS fighters chased me, but I hid in the buildings behind the school.[60]

In its assault on the al-Shaitat’s towns, ISIS used heavy artillery, remotely detonated bombs, and suicide bombers. It also unleashed some of its most hardened, feared fighters against the area after ISIS forces drawn from the local population had failed to take it.[61] When the ISIS fighters entered the town of Abu Hamam, as well as the villages of Gharanji and al-Kishkiyah, residents fled with nothing more than the clothes they were wearing. ISIS had announced via the mosque loudspeakers that it would guarantee civilians safe passage, but this was a trap, as those who fled into ISIS checkpoints were killed.[62] The adult men who remained were killed when ISIS took control. According to one survivor, on 15 August, “more than two hundred people” were killed in the desert, their bodies mutilated.[63] Many others were burned, crucified or hanged. Women were captured as “spoils of war.”[64]

Amid the violence, the massacre of the al-Shaitat also provided an opportunity to settle old tribal feuds. Inhabitants of Muhasan, of the Albu Khabour tribe, who had pledged allegiance to ISIS, tortured inhabitants of al-Shaitat villages and confiscated their properties after ISIS issued a decision to displace al-Shaitat residents. The attack was a retaliation for a previous attack by the al-Shaitat against Muhasan clans.[65] Such inter-tribal feuding would become a recurrent feature of ISIS violence in Deir Ezzor.

For months, ISIS continued its purge of al-Shaitat members, setting up checkpoints around the area. The al-Shaitat clan suffered violence even after they eventually returned to their homes, as one victim described:

In Gharanij, most of the animals had died of lack of water. There were lots of corpses on the road, the houses and the trenches.

There were several mass graves: one containing 30 corpses, another containing 40, another with 70 and another one with hundreds in the scrubland near Gharanij and Abu Hamam. In the houses, there were many dead people. Most of them were unrecognisable because they were decomposed and eaten by animals.[66]

After the discovery of several mass graves, sources estimated that in total, over 900 people were killed in several mass-casualty atrocities.[67] Some sources estimated it to be on the level of the organisation’s attack on Kobane, its mass killings of Christians, its attack on Camp Speicher in Iraq, and its killings of Yazidis in Sinjar. Later incidents demonstrated that ISIS maintained its grudge against al-Shaitat members: in May 2015, an al-Shaitat teenager, accused of killing ISIS members, was killed with a bazooka.[68]

‘Even if you find him, you won’t be allowed to bury him in a Muslim cemetery’: Public executions

After ISIS’ take-over of Deir Ezzor province, waves of executions followed. In July 2014, ISIS carried out dozens of executions in al-Mayadeen; residents recalled seeing 30 to 40 bodies hanging at the al-Bal’oum Roundabout.[69] The city of al-Mayadeen would, in fact, experience continuous violence and killing during ISIS rule. It was occupied by ISIS between 2014 and 2017 and renamed the “capital” of the group’s “al-Khair” province. ISIS also used the city as a training camp and gathering point for its fighters, as well as a place to store weapons and explosives. During this period, ISIS killed numerous civilians, including children.[70]

In some cases, ISIS even tried to make children carry out its executions, as one man saw during his detention by the group:

After three days, some ISIS fighters came, blindfolded me, and tied my hands. I could no longer control myself. He told me: “We’re going to execute you.”

I said: “Allah is my suffice, and the best deputy” [a common supplication].

They put us on a bus [and] we rode for about five hours. I heard different voices. Finally, we reached the destination.

We got off the bus, and they uncovered our eyes. We were in a fenced area with a lot of trees. I think we were on the Iraqi or Turkish border because we could see earth mounds. We entered a two-storey building. While we were there, we found out that the detainees with us were from the FSA, Jabhat al-Nusra and other people accused of fighting ISIS.

Finally, it turned out that we had been brought there because ISIS made a mistake. We were only meant to undergo a [repentance] session. There were five or six children among them.

[A fighter] stood in the doorway and told everyone: “You are going to re-enter Islam.” They let us have a break for an hour and made us take showers. They gave us Pakistani clothes, which we put on, and then we left.

There was an Iraqi called Abu Montasir, who led the unit. He gave us a lecture, saying we were disbelievers and that we would now become believers and learn about Shari’a law, and that we had to enter Islam again.

This continued for 15 days. Finally, Abu Montasir came again and made the takbir [shouting “God is great!”] and said Deir Ezzor had been liberated, the [Alawis] had been routed, the mountain had been seized and they had pledged allegiance to [ISIS].

Some of those present were very impressed and said we must pledge allegiance to [ISIS]. Some people there were ignorant, and five of them went out and pledged allegiance.

I told one of them: “Sheikh, my family does not know where I am, I can’t swear allegiance as I’m not ready.” Only five people left. Two days later, five soldiers from Tabqa airport were brought in, and they asked us to carry out retribution on them. They selected me, a second person, and one of the children who were with us.

They even brought a sword and put it on the table. They brought in the first soldier. They recited verses from the Quran and said: “Do it.” I couldn’t even hold the sword out of fear.

Abu Montasir kicked me so hard that I passed out. Somebody else executed one of the soldiers.

The child couldn’t do it, and he started crying. He couldn’t kill. So, Abu Montasir put his arm around him, held his hand and cut the soldier’s head off. Now the child had lost his voice. He couldn’t talk anymore because of what they had forced him to do, against his will. His eyes were red from crying.

They cleared the corpses from the yard and took us back inside. Then [Abu Monstasir] came back and lectured us, saying our hearts still had blasphemy in them and we couldn’t implement Islamic rule.

They kept us like this for about 40 days. But they got nothing from us. We were looking after the child, who could no longer speak. I took care of him because he wasn’t eating or drinking.[71]

Other videos of executions by children in Deir Ezzor, committed at the behest of ISIS, would later surface online.[72]

Victims’ families were prevented from burying their dead, sometimes for up to three days. The group rarely distinguished between old and young, or between men and women—all could be subjected to the ultimate punishment. Furthermore, ISIS often filmed its crimes and then published the videos through its online channels, as well as on screens they set up in squares and other public places. A family member of a victim related how this worked in practice:

Four months after [my cousin] was detained, we found out that ISIS was holding [him] in one of its prisons. We tried to visit him. They said he would be released after two days. Even his [immediate] family went to visit him, but they wouldn’t let them see him.

They told us that he would be released soon, and we tried to visit more than once, but they didn’t let us, and nothing changed. A few days later, we heard that he was going to be released on bail or for a fine. But we were all shocked when they told us there was no such plan; rather, they were preparing him to be executed.

We asked them: “What is he charged with?” They told us: “Smuggling weapons and collaborating with the Nusayris.”

After another week of waiting for any news about him, ISIS broadcast a report on their plasma screens, which they had installed in the streets, so people could watch everything the organisation released. His mother was shopping in the market when she saw it. Her son was executed along with another person on charges of smuggling weapons and dealing with [the regime]. She was in a terrible state when she saw it. When we heard, there was lots of shouting, and we went to the media point to make sure. The video was played again, and we saw how their sentence was carried out.

We went to the detention centre where he had been held and told them we wanted the body. They said he couldn’t be buried with Muslims. He was buried in a mass grave for people whom ISIS viewed as “non-Muslims.” We tried looking for him, but we couldn’t find him.

They told us: “Even if you find him, you won’t be allowed to bury him in a Muslim cemetery.”[73]

‘They’d brought their 10-year-old children’: Stonings and other violations against women in Deir Ezzor

ISIS specifically targeted women related to the group’s opponents, an effective technique to exact maximum offence in tribal social structures. In several cases, women from the region were stoned to death on charges of adultery. One woman recalled watching a woman stoned to death in a public square, as ISIS forced people to watch:

ISIS closed the roads and set up barriers, and people began to gather in the square. When everyone was there, they brought a woman out of a car, her head covered with a black bag. My sister asked what was happening. I told her I didn’t know.

I heard some men saying she was an adulteress and had been sentenced to be stoned to death. Then ISIS put the woman in a hole and told everyone to throw stones and pebbles at her until she was dead. They told everyone they were allowed to throw stones at her.

After 10 minutes of continuous stone-throwing, the woman appeared to be dead. Nobody knew who she was. I heard an ISIS fighter telling his friend that the woman wasn’t dead, and everyone had to throw stones at her again.

After another round of stone-throwing, he told his friend to check whether she was dead or alive. One of the fighters checked the woman’s pulse. He said she wasn’t dead. So, they told everyone to stone her yet again until they were sure that she was dead.

When she was finally dead, they carried the body to the car and told everyone to go home. This experience had a deep psychological impact on me, especially since I had a little sister.[74]

It was common for ISIS to make the residents of Deir Ezzor participate in stoning. “One time,” a witness said, remembering the stoning of two women:

I was doing something in the market and a hisba car showed up. They started shouting that there would be a stoning after noon prayers and that everybody had to be there, in front of the municipality building.

After about half an hour, they brought two women covered in black, and put them in a hole that had been prepared. Some stones were put next to the hole, and they put the women inside.

They’d brought their 10-year-old children to see the stoning. Most of them were Iraqis, but there were also some from […] Kuwait and Saudi Arabia.

They started carrying out the sentence, hurling stones at the women in the hole. The children were throwing stones and laughing. The women were stoned to death. What surprised me was how enthusiastic the children were about throwing stones, how they laughed, and how the [ISIS] leaders were encouraging them.[75]

Stoning on charges of adultery were not limited to women, even though they were the majority. A witness described how a young man was stoned to death outside a market:

[ISIS] fighters came in and ordered everyone present to go out to Albu Kamal Square to watch a stoning. He was a young man. They closed all the shops and forced everyone to go out and watch. We didn’t know who he was or what crime he was supposed to have committed. Four cars arrived, one carrying the young man. Another was loaded with stones. [ISIS] set up a security cordon around the area.

There was a circle, and the young man stood inside it. He was blindfolded and didn’t know who was around him. An [ISIS] member gave a speech about him and why they were going to stone him.

The ISIS fighters were wearing masks, and none of them could be identified. The young man was lying on the ground. An ISIS fighter went and brought a car carrying the stones. Then he took a big stone and threw it at the young man. He started bleeding.

It was a terrible scene. The young man tried to lower his face to the ground. Everyone picked up stones from the car and threw them. The young man was bleeding a lot from his face and his body. After he passed away, an ISIS member read a few lines, saying he had been cleansed of sins by the stoning.[76]

On other occasions, victims were thrown to their deaths from tall buildings, which would become a signature ISIS punishment in Deir Ezzor, particularly for people accused of homosexuality. Other victims were tied by their four limbs and torn apart or dragged to their death behind cars.

“Four cars arrived carrying ISIS fighters,” said a witness who saw victims thrown to their deaths from tall buildings:

After they had surrounded the place where we were standing, they got out. They were wearing black masks, and they had a young man with them who was blindfolded. What caught my attention was the young man’s self-confidence. He walked lightly, without any resistance, shouting or signs of sadness.

Those of us who were standing there started analysing it. One said: “Poor guy, why isn’t he afraid?”

Someone else said he was probably injected with something and that he’d lost his mind. People suggested lots of explanations.

A few minutes later, the young man was lifted onto the wall on the edge of the roof of a four-storey building. He was handcuffed and his eyes were closed. They pushed him off and he fell on his head. I saw him as he uttered his last moan.[77]

The UN Commission of Inquiry concluded that ISIS’ executions of women (and men) because of their gender, and the group’s use of sexual assault and rape, reflected part of a broader attack on the civilian population in Deir Ezzor, and constituted the crimes against humanity of murder, torture, rape, and other inhumane acts.[78]

‘In the end, he flogged us anyway’: Corporal punishment in Deir Ezzor

ISIS governance in Deir Ezzor was also influenced by tribal customs and rivalries. ISIS took advantage of the tribes that had suffered social and economic marginalisation; they were enlisted by ISIS for the enforcement of its strict interpretation of Shari’a. In one case, for instance, members of the al-Bkayyer tribe in Kasham shaved the moustache of a local leader for not following religious teachings. [79] Other punishments were far more serious, and mirrored the practices enacted by ISIS in the other territories under its control, including amputations. One local recalled how a child from Hajin was punished with amputation for allegedly having stolen something:

A group of [ISIS] members arrived outside the mosque. They didn’t even go in to pray. They surrounded the mosque. Then one of them stood up and gave a speech, saying: “This person is a thief, and his hand will be cut off to fulfil Shari’a law.”

I don’t remember what he had [allegedly] stolen. Then they removed his blindfold. I looked at him and I recognised him. He was just a child, from Hajin. I thought that even if he had stolen something, he could be disciplined and reformed. “Why do they need to cut his hand off?” I thought.

His family begged them, but in vain. A few people tried to intervene, but [the ISIS fighters] pointed their weapons and told them that anyone trying to interfere would be killed.

Nobody was allowed to leave; we all had to stay and watch. People were in a terrible state. The signal was given to carry out the amputation. The boy’s head was lowered on the table and his hand was extended across it. The ISIS members had a dispute about whether to cut just the hand or the entire forearm.

Finally, they agreed to cut just the hand. Then they brought a nurse who belonged to the group, who gave him a local anaesthetic. After that, they brought medical equipment, a scalpel. His hand was cut off, and blood covered the table.

When the bleeding started and his hand was cut off, they wrapped it in a piece of cloth. Some people fainted or threw up. It was a terrible scene, unlike anything we had seen before. Finally, he was taken to the hospital. I saw everyone there had oppression, fear and exhaustion in their eyes.[80]

Floggings were common too, especially for women. “I was sentenced to be flogged,” a victim told us. She described the psychological impact of being whipped in front of a mosque:

They took me to the mosque at the time of the afternoon prayer, along with a worker who was being held with me and was later forced to take a Shari’a course. They gathered the public—men, women and children—and told them that we were spreaders of corruption in the land [a Quranic reference], that we were leading Muslims astray, and that we were sentenced to 350 lashes each.

I knew I couldn’t even handle 10 lashes because I’m quite small. But they were committed to carrying out the sentence, ordered by the head of the hisba at the time, Abu Anas al-Iraqi. One of them began to flog us. When he reached 100 or 150 lashes, he got tired and asked a colleague to finish the job for him.

But the colleague refused. When I arrived, I had talked with him and told him that I was being oppressed and ISIS was oppressing me. When I saw him refuse, I realised that some members of the group weren’t happy with the sentences being carried out against civilians.

But in the end, he flogged us anyway, right to the end of the sentence. After that, they got pieces of cardboard and hung them around our necks. The signs said: “This person is corrupt and spreads corruption among Muslims.” We had to stay like that for two hours.

These words had more psychological impact on me than the flogging. I started hearing people discussing us. Some said we should be killed. But what caught my attention was the woman from ISIS, saying that we were sharing pornography. This really crushed me.[81]

At the time, the countryside of Deir Ezzor was suffering from deep poverty, in part because ISIS had imposed regressive economic laws and levied heavy taxes, including on currency exchanges. “We were banned from buying and selling except with this currency,” one local said, adding that “violation was punishable by imprisonment and public flogging.” [82] As a result of the lack of development and stifling economic policies, people felt the economy stagnated and led to losses for people who owned small businesses and shops. Some tried to make a living by “illegal” means, for example, by selling tobacco, even though there were severe risks involved:

One evening in June 2015, the hisba raided and searched my home. They found three packets of tobacco. They took me to their base in al-Saada, the village next to mine. They interrogated me and asked me where I was buying it from. When I refused to tell them, they punished me for being a tobacco seller. They said it was immoral and that I would receive 40 lashes. That wasn’t enough: they also fined me 50,000 Syrian lira [around $250]. Then they left me, late at night, after forcing me to write a declaration that I would not do it again, because tobacco is a vice.

But because of extreme poverty and hunger, and because nobody else in our household could work, I went back to selling tobacco again. They arrested me again and took me to the hisba base and detained me there until the next day.

Then they gave me 80 lashes. With each lash, I was screaming at the top of my voice from the intense pain. I was losing consciousness. The only thing that gave me strength was thinking of my disabled son and my husband, who is paralysed. They have no-one to provide for them in this world besides me, after God.

All that still wasn’t enough for them. They fined me another 200,000 Syrian pounds [about $1,000]. After that, they tied me to an electricity pylon on the highway between Deir Ezzor and Hasakeh from 9 am until 3 pm, and everyone looked at me. I wished I was dead.[83]

Despite its strict laws, ISIS could be highly selective in its enforcement when they were violated by its own members. The testimony of a muezzin, who does the call to prayer at a mosque, showed how this worked:

I arrived to make the fajr [dawn] call to prayer. I could hear laughing. There was a stream passing through the mosque. I was shocked to see an ISIS fighter, from China or Kazakhstan, having sex with a woman in the stream. The scene was disgusting. They disrespected the sanctity of the mosque. I made a sound so he would hear me. As soon as he heard my voice, he quickly got out, put on his clothes and hit me.

He asked me: “How did you get in?”

I told him: “I’m the muezzin, I came to give the call to prayer.” He told me to get out and started beating and insulting me.

I went out in front of the mosque, and he locked the mosque door. Some people had come to pray, so I told them: “Today there is no prayer at the mosque.”

I went back the next day for the noon prayer, and I was arrested from the mosque by the hisba, who accused me of inciting people not to pray. I knew that it was a plot by the fighter. They gave me 40 lashes in the marketplace in Hajin and I was imprisoned for 20 days in Albu Kamal. [84]

‘I cried like I had never cried before’: Torture in ISIS’ prisons in Deir Ezzor

According to the UN Commission of Inquiry, ISIS’ use of torture as part of its attacks on the civilian population in Deir Ezzor amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity.[85] Conditions inside ISIS-controlled detention facilities were awful, characterised by overcrowding and horrendous abuses.

“The cell held about 22 people, on charges of communicating with apostates,” one former detainee said, remembering how:

They beat me severely with every weapon they had. I was screaming in pain, and I knew that I was innocent and that I didn’t do any of what they were accusing me of.

They tortured me with a method called the “scorpion,” which is when they tie your hands behind you and then attach them with a rope to the ceiling. They beat me with a green hose, like a water hose. I remember that it was a metre and a half long. It hurt so much, my body was in a lot of pain, but nobody could help me.

After being tortured for a while, I was transferred to an ISIS judge. They couldn’t prove any of the charges against me. The judge ruled that they should confiscate all my devices, including a computer, modem, large batteries and internet devices, all of which were worth about $2,500. They also fined me a “deterrent fine” of $1,200 dollars so I wouldn’t use these devices again.

I was detained for three days at their security detachment in Hajin, then 12 days at their intelligence branch in Albu Kamal. I was sentenced to a full month in prison.

I saw with my own eyes some horrible cases of punishment that happened in front of everyone. The [cell] was six metres long, with about 20 people in it. An ISIS guard would come in, take one of the inmates and slaughter him in front of everyone. No-one dreamed of denying anything. You had to confess in detention.

They used to take us out in the courtyard of the prison and bring out a big plasma screen and show what they called “state bulletins.” They were talking about their killings in other regions, on countless charges. We were terrified. The Coalition was bombing the organisation’s positions with planes and machine guns, believing that they were bases, but in reality they were prisons.

ISIS kept their captives in their bases so that the Coalition would not target them. They would go out in their cars and the only people left in the buildings would be the detainees. We would be the victims and they would not lose any of their fighters.

After a while, I was transferred to the village of al-Ramadi for about 30 days. As well as being jailed, I was sentenced to 400 lashes, each 50 in a different village. I knew one of the villages, which was in Albu Kamal. I was given 50 lashes in front of a crowd there. I don’t know what this was for. They said it was a deterrent to anyone who tempts himself to work with the apostates.

They gave me 50 lashes at the al-Fayhaa Roundabout in Albu Kamal, and 50 more in another village, in front of the mosque, after the worshipers left evening prayers. I don’t know where the rest of the lashes were because I was blindfolded most of the time.[86]

Another victim was similarly tortured in detention—one of many cases documented by the research team across Deir Ezzor. He recounted the story of his confession of being affiliated to the FSA, but how this did not get him killed, due to sheer luck:

They detained me and took me to some unknown location. I was blindfolded, then suspended by my hands with a chain hanging from the ceiling, and with my feet not quite touching the ground. Their first question was: “Are you with the FSA?” I told them no, and said I challenge anyone to prove that claim.

The second question was: “Where is your uncle’s car?” I told them he had fled with it to Damascus.

They kept trying to intimidate and terrify me, using beating and cursing. After about an hour, one of them started to beat me really hard. I started screaming: “I’ll confess!” but [the interrogator] kept on beating me. I told him the car was in al-Mayadeen, at my relatives’ house, and that my father is FSA, I am FSA, and my mother is FSA and that we all fought [ISIS].

I was talking unconsciously, my eyes were closed, I don’t know who was in the room. Anyway, the beating continued.

At the sound of my screams and shouts, some other ISIS members ran in. They opened the door of the room and stopped the person who was beating me. Then they took me down to the ground and gave me water to drink. They took off my blindfold. I was surprised, they didn’t seem to know this person who was beating me so badly.

He didn’t speak, he was mute. He was an Iraqi, about 16 years’ old. He had taken advantage of their busy period and come into the room. I realised that there had been no one in the room except me and him.

So, I thanked God that no one else had heard what I said. My pain and fear were mixed with relief. I didn’t know whether to laugh or cry. I confessed to things I hadn’t done, but finally the confession was in front of a mute person.[87]

On occasions, ISIS even inflicted torture on family members of prisoners. One man spoke of how ISIS had tortured his son in front of him at a detention centre to extract a confession:

[ISIS] arrested me on charges of selling tobacco, as I was selling cigarettes, shisha tobacco and charcoal. My arrest was a trap. They sent a relative to my house to buy tobacco and then a patrol, headed by an Iraqi called Abu Rahma, surrounded my house and arrested me.

My son wasn’t at home at the time, but when he came back, his mother told him what had happened: “One of your relatives snitched on your father, and a patrol raided us and arrested him. So, my son stood at the door of the house, and when the relative came, my son beat him, insulted him, and told him that [ISIS] are Kharijites.”[88]

This person reported on my son, and a patrol came and arrested him too, while I was in prison. They brought my son, [F.], threw him down in front of me in the cell, beat him, humiliated him and whipped him with a plastic pipe, like the one on a shatafa [bidet].

They were beating him all over his body, and it made me so angry. I was handcuffed and sitting on my knees, so I shouted at them: “Have some fear of God! If this makes you happy, take him to another room and kill him, don’t beat him in front of me!”

So, Abu Rahma loaded a pistol and put it in my son’s mouth and said to me: “How about I kill him in front of you?”

I said: “If your religion commands you to do that, then do it.” I had totally lost my mind and no longer had any control over my words. I didn’t know what I was saying.

Then they dragged my son and hung him in front of the cell for an hour, until he lost consciousness. I shouted at them several times to let him go.

There was someone in the cell with me who told me: “Don’t lose your temper, they want to kill you. Don’t blaspheme or admit that you sell tobacco. They’re trying to provoke you to say something wrong and then they’ll kill you.”

I started crying. I cried like I had never cried before. I was in a state of absolute fury at the injustice. After that, my son was imprisoned with me. I spent seven days in prison before I was given 120 lashes, released and forced to take a Shari’a course.[89]

Deir Ezzor under siege

After ISIS pushed Nusra and its allies out of Deir Ezzor, ISIS resumed the siege on government forces still in control of the western bank of the Euphrates within Deir Ezzor city. In late 2014, there were heavy clashes between both sides that killed over a hundred people;[90] according to SOHR, regime forces at that point used chlorine gas to halt ISIS attempts to capture Deir Ezzor’s airbase, where the forces of the 104th and 137th brigades of the Syrian army were holed up.[91]

The siege was marked by frequent attacks by ISIS, regularly fired artillery and missiles at the areas under siege with little regard for the civilian population. Many civilians were killed as a result. Meanwhile, an estimated 100,000 people who remained in Deir Ezzor were unable to get out, unless they could afford sky-high prices to be airlifted out of the city, and thus were left dependent on airdrops from the UN’s WFP to survive.[92] The situation worsened after the fall of Palmyra to ISIS. At that point, all supply lines in and out of the city were cut off, and citizens suffered from a lack of food, drinking water and medicine. Regime forces were reportedly considering evacuation.[93] By 2016, the city’s electricity supply had fallen to five per cent of its pre-ISIS levels.[94]

In February 2016, the Justice for Life Observatory, an NGO in Deir Ezzor, described the situation facing the besieged population in the city. Describing 420 days of siege, the NGO’s report stated that ISIS had:

Cut off the electrical power supply from the station of the al-Tayem oil field which used to provide electricity for the besieged neighbourhoods [and] up till now those neighbourhoods under siege do not have electricity. The locals hence use candles as an alternative given the overly expensive cost of fuel required for running the generators or the lanterns fuelled by kerosene oil.

Moreover, cutting off the electrical power supply resulted negatively on the services that are based electricity [sic], most important of which is drinking water, where water is being pumped for the locals from one main water station that is powered by a generator for three hours on daily basis; leading to a decrease in that period up to three hours every two or three days. As a result, water is not provided for all houses, and it is not sterilized due to the lack of the liquefied chlorine.

As the siege escalated, four bakeries had to shut down because their supply of fuel stopped. And in order to preserve the reservoir of the wheat by Assad regime officials [sic], this resulted to a state of flour inadequacy for all bakeries. This led to the fact that the amount of the produced bread where [sic] not enough to cover all the needs of bread for the civilians there. The civilians have to wait in line for 10-12 hours in order to get their allocations of bread.

According to the NGO that produced the report, regime forces capitalised on the suffering and economic desperation of young people in besieged Deir Ezzor to recruit them into armed groups; it even accused Assad at best of not doing enough to break the siege, and at worst of working with ISIS to starve the people of Deir Ezzor.[95]

Nevertheless, clashes between ISIS and the regime continued throughout 2016, with ISIS targeting pro-government fighters and their families in besieged areas.[96] Supported by Hezbollah fighters and Russian airstrikes, pro-government forces made some gains against ISIS but suffered a setback when a series of US-led Coalition strikes in mid-2016 killed nearly a hundred Syrian army soldiers.[97] The incident led to ISIS re-taking territory around Jabal al-Tharda, but more significantly, it caused a major diplomatic conflict that scrapped a nationwide ceasefire negotiated by the US and Russia over the course of several months.[98]

During the first half of 2017, with the SDF and the US-led Coalition focused on the fight for Raqqa, the Syrian army took control of most of southern Raqqa province and gradually advanced towards Deir Ezzor. Although it was losing ground across Syria, ISIS launched several last-ditch assaults on besieged areas of Deir Ezzor city and, that January, heavy fighting forced the UN to suspend airdrops.[99] By February 2017, ISIS separated the Syrian army airbase and the civilian neighbourhoods, and civilians were fearful that massacres would occur should the besieged areas fall to the group.[100] Eventually, ISIS’ attacks were repelled, and over the summer of 2017, the Syrian army, supported by Russian airstrikes, managed to break the three-year siege of Deir Ezzor.[101] Yet again, however, civilians suffered under the aerial campaign when Russian airstrikes killed 34 civilians fleeing on ferries during the attempts to clear ISIS from the surroundings of Deir Ezzor city.[102]

Baghouz and the fall of ISIS

To the east of the Euphrates, the SDF, supported by the US-led Coalition, started the campaign to liberate the Deir Ezzor countryside in the autumn of 2017. By then, Raqqa had been secured and the eastern bank of the Euphrates in Deir Ezzor was fast becoming the last ISIS holdout. The SDF campaign sought to build alliances with tribal structures across Deir Ezzor and established the Deir Ezzor Military Council, which included fighters from the most prominent tribal groups. Unsurprisingly, the al-Shaitat tribe, which had suffered so during the ISIS rule, was one of the prominent tribes to join the campaign along with the al-Baggara tribe in western Deir Ezzor and al-Bkayyer in the province’s north.[103]

Over the course of the next months, the SDF took control of the major oil and gas facilities on the eastern bank of the Euphrates. By the end of 2017, ISIS fighters were pushed into a final pocket of territory stretching around 40 kilometres from Hajin to Baghouz along the Euphrates. To the west, pro-government forces took control of the border town of Albu Kamal. Although it was rapidly losing territory, ISIS demonstrated a capacity to still strike on both sides of the Euphrates. In Gharanji, the al-Shaitat village where ISIS had established a base of operations, ISIS fought pitched battles with SDF forces, using car bombs inside the town.[104] In May 2018, ISIS killed 26 Russian soldiers in al-Mayadeen.[105] Earlier, far to the west of Deir Ezzor and in the rear of the Syrian government operations, ISIS killed at least 128 civilians in the village of al-Qaryatayn.[106]

Despite these attacks, ISIS increasingly looked like a spent force. Faced with massive manpower losses, ISIS instituted the enforced conscription of all men under the age of 30 in its remaining territories.[107] The group’s impending collapse prompted all actors involved in the Syrian conflict to position themselves for a post-ISIS future. Turkey, concerned by the prospect of a semi-autonomous Kurdish area in northeast Syria, invaded northern Syria in early 2018. This brought the SDF campaign to a temporary standstill: operations were paused, and fighters relocated from the Euphrates to Kurdish-majority areas around Afrin.[108] Operations resumed, although Turkish attacks in Kobane and Tel Abyad in October 2018 precipitated another pause.[109]

Additionally, despite informal commitments not to conduct attacks on each other, the US-backed SDF campaign rubbed up against the Russian-backed government campaign. Both sides sought to secure territory and strategic natural resources. Before long, the two sides came to blows. In September 2017, Russian warplanes struck SDF fighters.[110] Several months later, as many as 300 pro-government troops and Russian Wagner Group paramilitaries were killed by the SDF and US special forces when attempting to take over the Conoco gas plant.[111] In late 2018, President Trump announced a withdrawal of US troops from Syria, but the decision was later overturned, and American forces increasingly focused on countering the influence of Iranian-backed militias, which had established a strong presence in Deir Ezzor.[112]

Despite the geopolitical wrangling, ISIS was gradually squeezed out of the final pockets it controlled. Hajin, the group’s “last capital,” was taken by the SDF in December 2018.[113] Several thousand ISIS fighters were besieged in a four-square-kilometre area around Baghouz al-Fawqani, and an exodus of civilians from the area significantly complicated the military operation.

Some ISIS members surrendered; others decided to fight until the bitter end. After 18 weeks of intense fighting, the SDF and US-led Coalition forces took control of Baghouz. In total, the SOHR estimated that 1,168 ISIS members and commanders were killed in this final operation, along with 630 SDF fighters and 713 prisoners who were executed by ISIS.[114] Families of ISIS fighters were transferred to the al-Hol camp in Hasakeh province, while surrendering ISIS fighters were imprisoned in SDF prisons holding over 12,000 Syrian, Iraqi and foreign ISIS detainees.

The aftermath

Although ISIS’ “caliphate” had finally been defeated, its violence would reverberate across Deir Ezzor for many years.

Many of the people interviewed for this report in Deir Ezzor spoke of the trauma of the period and several displayed symptoms of post-traumatic stress disorders, without much if any mental health support being provided to them.[115] The levels of destruction were appalling: 90% of Deir Ezzor city’s buildings and infrastructure were destroyed, compared with 50% in al-Mayadeen and Albu Kamal.[116] The population of Deir Ezzor appeared opposed to “reconciliation” efforts made by the Syrian regime;[117] but there were also reports of local grievances against the Kurdish-led administration as well.[118] Protests against the Autonomous Administration remain a consistent feature of life in Kurdish-held areas of the province, but particularly in Arab tribal areas of eastern Deir Ezzor.

After a decade of conflict and six years of ISIS rule, communities in Deir Ezzor still fear ISIS could make a comeback in the region. As the group morphed into an insurgency, ISIS’ tribal fighters remained in the area and enjoyed the continued protection of their tribes.[119] Moreover, following the 2022 attack on the Ghuweran prison in Hasakeh, when over a hundred ISIS members managed to escape, attacks against the SDF, government forces and allied Iranian-backed militias increased rapidly.[120]

Deir Ezzor will always be remembered as the place where ISIS fell. But as political disagreement over control of the province and its resources persists, it may well be the place where ISIS, if given the opportunity, could seek to reconstitute itself in the future.

Footnotes

[1] Rudayna al-Baalbaky and Ahmad Mhidi, Tribes and the rule of the “Islamic State”: The case of the Syrian city of Deir ez-Zor (Konrad Adenauer Stiftung, December 2018), p.21 <https://www.kas.de/documents/266761/4421641/Tribes+and+the+Rule+of+the+Islamic+State+Organization+-+Part+2.pdf/f342c609-141b-ea69-b30a-6ce01676661a?version=1.2&t=1545393667940> accessed 21 August 2023.

[2] Ibid.

[3] Map Action, ‘Syria Governorate Maps: Deir ez-Zor Governorate’ (4 July 2016) <https://maps.mapaction.org/dataset/217-2938/resource/682e96b0-b538-47d4-a84d-33dbdc1e020b> accessed 21 August 2023.

[4] Abdullah Hanna, ‘How the Syrians narrated the Armenian tragedy in 1915 and dealt with it’ (Ar.) Duffah Talteh (9 March 2018) <https://diffah.alaraby.co.uk/diffah/print//revisions/2018/3/8/%D9%83%D9%8A%D9%81-%D8%B1%D9%88%D9%89-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%B3%D9%88%D8%B1%D9%8A%D9%88%D9%86-%D8%A7%D9%84%D9%85%D8%A3%D8%B3%D8%A7%D8%A9-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D8%B1%D9%85%D9%86%D9%8A%D8%A9-%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%85-1915%D9%88%D8%AA%D8%B9%D8%A7%D9%85%D9%84%D9%88%D8%A7-%D9%85%D8%B9%D9%87%D8%A7> accessed 21 August 2023.

[5] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.26.

[6] Ghassan Sheikh Khafaji, Golden Biography: Deir ez-Zor, Bride of the Euphrates and the Syrian Jazeera (Ar.) (House of the Raslan Foundation for Printing, 2019), pp.320-321.

[7] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.26.

[8] Ibid.

[9] Ziad Awad, Deir Al-Zor after Islamic State: Between Kurdish Self Administration and a Return of the Syrian Regime (European University Institute, March 2018) <https://cadmus.eui.eu/bitstream/handle/1814/52824/RPR_2018_02_Eng.pdf?sequence=4> accessed 21 August 2023.

[10] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.26.

[11] CEIC, ‘Syria Crude Oil: Production, 1960-2021’ (n.d.) <https://www.ceicdata.com/en/indicator/syria/crude-oil-production> accessed 21 August 2023.

[12] Baalbaky and Mhidi, pp.26-27.

[13] Ibid, p.27.

[14] Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics, ‘Syria Population Census, 2004’ (Ar.) (n.d.) <https://web.archive.org/web/20151208115353/http://www.cbssyr.sy/General%20census/census%202004/pop-man.pdf> accessed 17 August 2023.

[15] Baalbaky and Mhidi., p.27.

[16] Charles Lister, The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency (Oxford University Press, 2015); Peter Neumann, ‘Suspects into Collaborators’ London Review of Books (London, 3 April 2014).

[17] Awad.

[18] Individual testimony #83, focus group session 2.

[19] Individual testimony #110, focus group session 4.

[20] Individual testimony #19, focus group session 3.

[21] BBC Arabic, ‘Syria: Security uses batons and teargas to prevent mass demonstration from reaching the centre of Damascus’ (London, 15 April 2011) <https://www.bbc.com/arabic/middleeast/2011/04/110415_syria_firday_demo> accessed 21 August 2023.

[22] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.27.

[23] Ibid.

[24] Ibid.

[25] Al Jazeera English, ‘“Dozens dead” in Syria after Friday protests’ (Qatar, 13 August 2011) <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2011/8/13/dozens-dead-in-syria-after-friday-protests> accessed 21 August 2023.

[26] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.28.

[27] Khaled Yacoub Oweis, ‘Assad’s Aleppo focus allows rebel gains in Syria’s east’ Reuters (14 August 2012) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-crisis-east-idUSBRE87D0OH20120814> accessed 21 August 2023.

[28] Shelly Kittleson, ‘The Changeling of Deir ez-Zor’ New Lines Magazine (18 December 2020) <https://newlinesmag.com/reportage/the-changeling-of-deir-ez-zor/> accessed 21 August 2023.

[29] Damien Cave and Dalal Mawad, ‘Prime Minister’s Defection in the Dark Jolts Syrians’ The New York Times (New York City, 6 August 2012) <https://www.nytimes.com/2012/08/07/world/middleeast/syrian-state-tv-reportedly-attacked-as-propaganda-war-unfolds.html>; Martin Chulov, ‘Syria’s ambassador to Iraq defects in major blow to regime’ The Guardian (London, 11 July 2012) <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2012/jul/11/syria-ambassador-iraq-defected-opposition> accessed 21 August 2023.

[30] Awad.

[31] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.28.

[32] Ibid.

[33] Ibid.

[34] Individual testimony #11, focus group session 5.

[35] Individual testimony #19, focus group session 3.

[36] Ahmad Khalil, ‘Crossing the Bridge of Death in Deir Ezzor’ Syria Deeply (15 November 2013) <https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/syria/articles/2013/11/15/crossing-the-bridge-of-death-in-deir-ezzor> accessed 21 August 2023.

[37] Fernande van Tets, ‘Syria: 60 Shia Muslims massacred in rebel “cleansing” of Hatla’ The Independent (London, 13 June 2013) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/syria-60-shia-muslims-massacred-in-rebel-cleansing-of-hatla-8656301.html> accessed 21 August 2023.

[38] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.30.

[39] Ibid., p.29.

[40] Awad.

[41] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.31.

[42] Ibid.

[43] Ibid.

[44] Saad Abedine and Jason Hanna, ‘68 killed as Islamist groups fight each other in Syria, group says’ CNN (11 April 2014) <https://edition.cnn.com/2014/04/11/world/meast/syria-civil-war/> accessed 21 August 2023.

[45] Karen Leigh, ‘As ISIS Advances in Eastern Syria, Jabhat al-Nusra Faces Loss of Control’ Syria Deeply (16 July 2014) <https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/syria/articles/2014/07/16/as-isis-advances-in-eastern-syria-jabhat-al-nusra-faces-loss-of-control> accessed 21 August 2023.

[46] Barbara Surk, ‘Jihadi group captures Syrian border town’ Associated Press (1 July 2014) <https://apnews.com/b2a2352009394ed4a0d5c5dbf93941a2> accessed 21 August 2023.

[47] Ibid.

[48] Alexander Dziadosz and Tom Perry, ‘Islamic State expels rivals from Syria’s Deir al-Zor – activists’ Reuters (14 July 2014) <https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-syria-crisis-east-idAFKBN0FJ1I020140714> accessed 21 August 2023.

[49] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.34.

[50] Al-Arabiya News, ‘NGO: ISIS expels thousands in east Syria’ (6 July 2014) <https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2014/07/06/NGO-ISIS-expels-thousands-in-east-Syria> accessed 21 August 2023.

[51] Omar Abu Layla, ‘Daesh’s Forgotten Massacre in Deir al-Zour’ (Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 24 October 2022) <https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/daeshs-forgotten-massacre-deir-al-zour> accessed 21 August 2023.

[52] Interviews with Shaitat members, April and May 2023.

[53] Abu Layla .

[54] Ibid.

[55] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.35.

[56] Individual testimony #183.

[57] Abu Layla.

[58] Individual testimony #78.

[59] Quotes from Abu Layla, ‘Daesh’s forgotten massacre’.

[60] Individual testimony #183.

[61] Interviews with al-Shaitat members, April and May 2023.

[62] Ibid.

[63] Massar, ‘Al-Shaitat massacre, as narrated by one survivor’ (8 December 2021) <https://massarfamilies.com/al-shaitat-massacre-as-narrated-by-one-survivor/?lang=en> accessed 21 August 2023.

[64] Interviews with al-Shaitat members, April and May 2023.

[65] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.34.

[66] Individual testimony #89.

[67] BBC, ‘Syria conflict: 230 bodies “found in mass grave” in Deir al-Zour’ (London, 17 December 2014) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-30515483> accessed 21 August 2023.

[68] Gianluca Mezzofiore and Arij Limam, ‘Syria: Isis executes al-Sheitaat tribe teenager with bazooka in Deir al-Zour’ International Business Times (21 May 2015) <https://www.ibtimes.co.uk/syria-isis-kills-shaitat-tribe-teen-bazooka-deir-al-zour-1502356> accessed 21 August 2023.

[69] United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), ‘9th Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’ A/HRC/28/69 (5 February 2015), Annex 2, para 75.

[70] Interviews with al-Mayadeen residents, April and May 2023.

[71] Individual testimony #129.

[72] Al-Arabiya News, ‘Disturbing ISIS video shows kids beheading and shooting prisoners (10 January 2017) <https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2017/01/10/Disturbing-ISIS-video-shows-kids-beheading-and-shooting-prisoners> accessed 21 August 2023.

[73] Individual testimony #179.

[74] Individual testimony #66.

[75] Individual testimony #99.

[76] Individual testimony #60.

[77] Individual testimony #17.

[78] UNHRC, ’9th report’, Annex 2 para.185.

[79] Baalbaky and Mhidi, p.34.

[80] Individual testimony #83.

[81] Individual testimony #87.

[82] Individual testimony #17.

[83] Individual testimony #22.

[84] Individual testimony #124.

[85] UNHRC, ’9th report’, Annex 2, para.171.

[86] Individual testimony #28.

[87] Individual testimony #123.

[88] Arebel sect in early Islam, although the term is also used to refer to purported apostates in general.

[89] Individual testimony #192.

[90] SOHR, ‘111 killed in 3 days of violent clashes between regime forces and ISIS in Der-Ezzor’ (6 December 2014) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/7696/> accessed 21 August 2023.

[91] SOHR, ‘Regime forces use chlorine gas to stop ISIS advances in Der-Ezzor military airport’ (6 December 2014) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/7693/> accessed 21 August 2023.

[92] Hamza Abdalla, ‘How do you drop food from 17,000 feet into a conflict zone? Watch our video’ (World Food Programme, 16 October 2017) <https://www.wfp.org/stories/how-do-you-drop-food-17000-feet-conflict-zone-watch-our-video> accessed 21 August 2023.

[93] NOW Lebanon, ‘Syria regime prepares Deir Ezzor evacuation’ (Beirut, 26 May 2015) <https://web.archive.org/web/<20171019184314/https://now.mmedia.me/lb/en/NewsReports/565341-syria-regime-prepares-deir-ezzor-evacuation> accessed 21 August 2023.