Operational Context

This section briefly overviews the dynamics in each of the nine governorates and some of the operational challenges and considerations they faced at the time of the consultations.

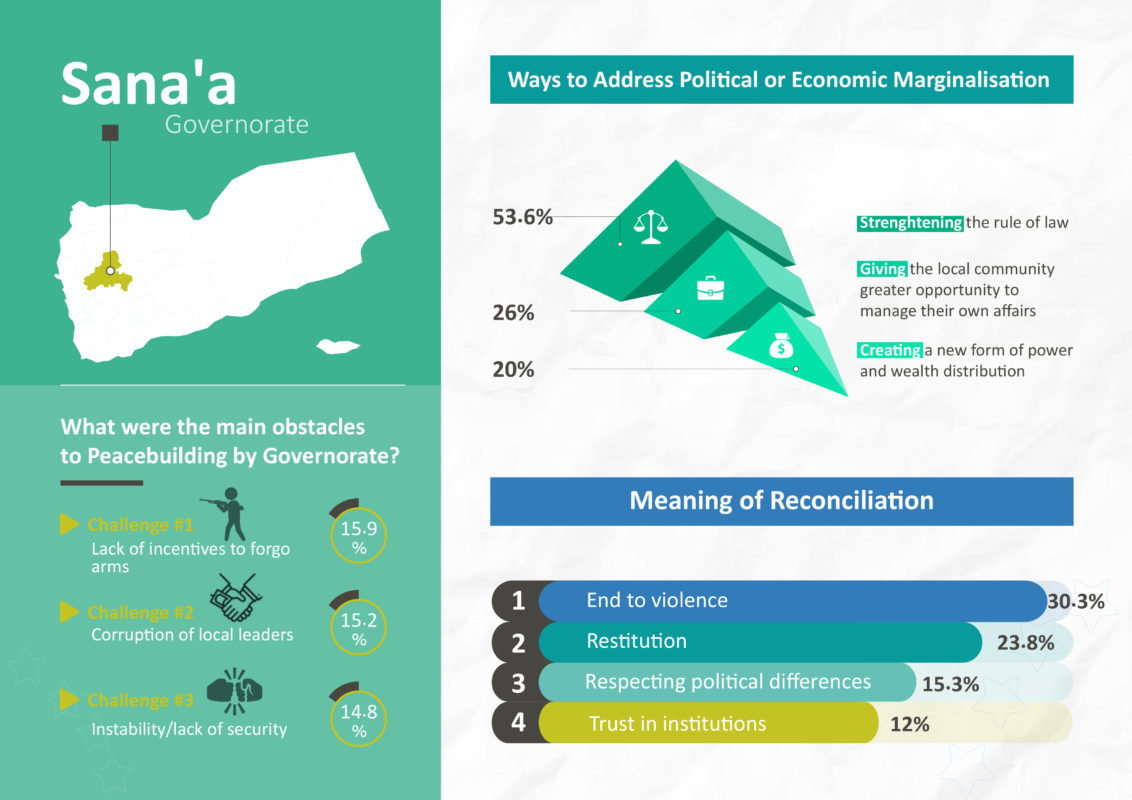

Shabwah

Shabwah is a sparsely populated, resource-rich governorate in southern Yemen. Its tribes were often involved in past skirmishes with the government over access to oil and gas infrastructure, ports and other resources. Along with Hadramawt and Ma’rib, Shabwah accounts for a significant portion of Yemen’s oil and natural gas production, which is of immense strategic value for the warring parties. Large parts of Shabwah remain under the control of the Internationally Recognised Government of Yemen (IRGY); the government’s relevance and leverage in the conflict are largely contingent on those three regions. In August 2019 the IRGY lost control of Aden, the country’s temporary capital, to the Southern Transition Council (STC). The STC and the Houthis are vying for control of Shabwah to help make their ‘post-war’ visions of Yemen economically viable. The Houthis recently launched a massive assault; as of September 2021, the battle intensified and three districts in Shabwah fell under their control, with increasing tension between IRGY and STC in the remaining districts.

Shabwah has a small population of approximately 658,000 – approximately 95 per cent of whom require assistance according to the UN Office for the Coordination of Humanitarian Affairs (OCHA). The governorate’s health services are provided through public hospitals and health centres, which receive limited support from the central government and local authorities. These services do not meet the needs of the population due to a lack of medical staff and equipment and inadequate financial allocations. Consultations in Shabwah were conducted during a relatively peaceful period. Due to a lack of technical capacity and resources, a hybrid community dialogue conference was organised in Ataq.

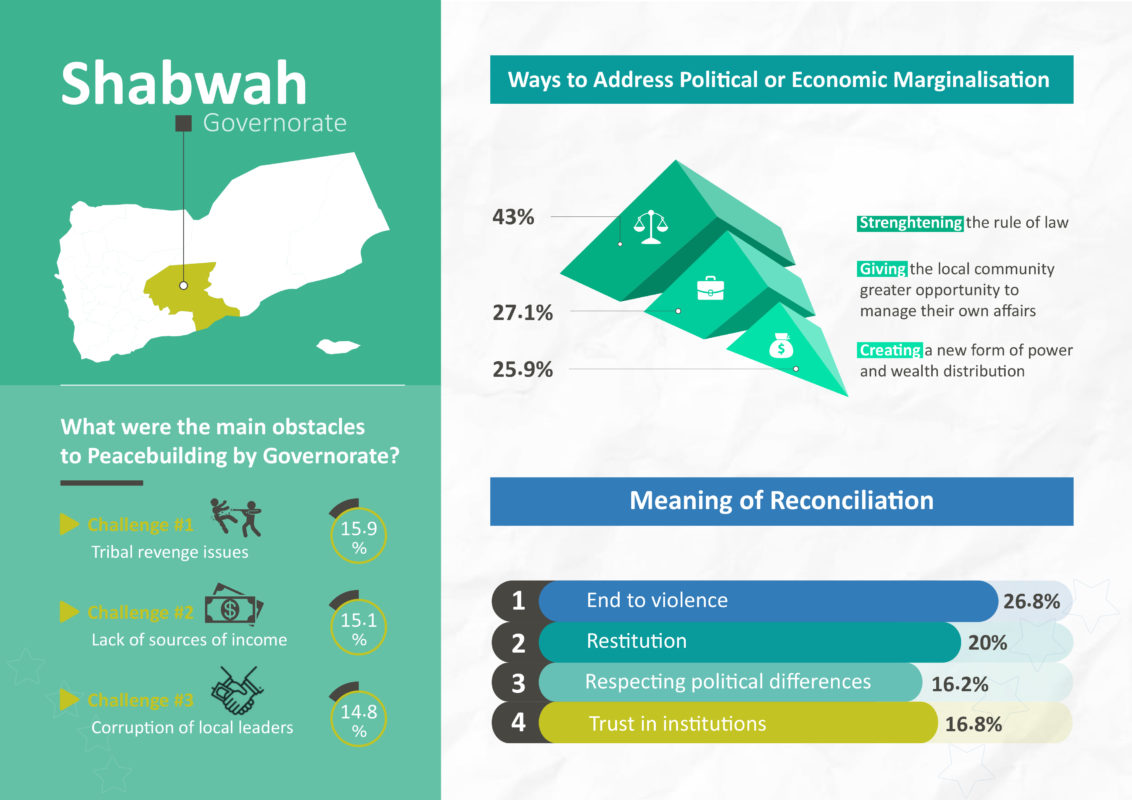

Taiz

Taiz is one of the country’s most populated governorates; approximately 2.6 million people live there, though the population has likely dwindled due to the conflict. It has experienced more armed conflict than other governorates: casualties in Taiz comprise one-fifth of the death toll in Yemen between 2015 and 2019. While the IRGY nominally controls some areas of the governorate, Taiz has in effect been under a siege imposed by the Houthis since 2015 that has disrupted the distribution of and access to humanitarian and medical assistance for thousands of residents.

Vital medical units in Taiz have been destroyed by on-going Coalition–Houthi confrontations, leading to widespread disruptions in access to services. There are only two public hospitals and one military hospital that serve the entire population. These receive some support from international non-governmental organisations, but are still short of medicines. Due to the decline in health services and a scarcity of clean drinking water, there have also been major epidemics of infectious diseases such as cholera. Traditionally, Taiz has a more diversified economy than most Yemeni governorates; it specialises in agriculture and animal husbandry, and a significant workforce is engaged in fishing along the Red Sea coast and working in a number of industrial plants.

During the consultations in Taiz, there were multiple fighting fronts within the governorate. Fighting would often and sporadically break out, and shelling would suddenly hit various parts of the city, causing short-term pauses and delays in the local teams’ operations.

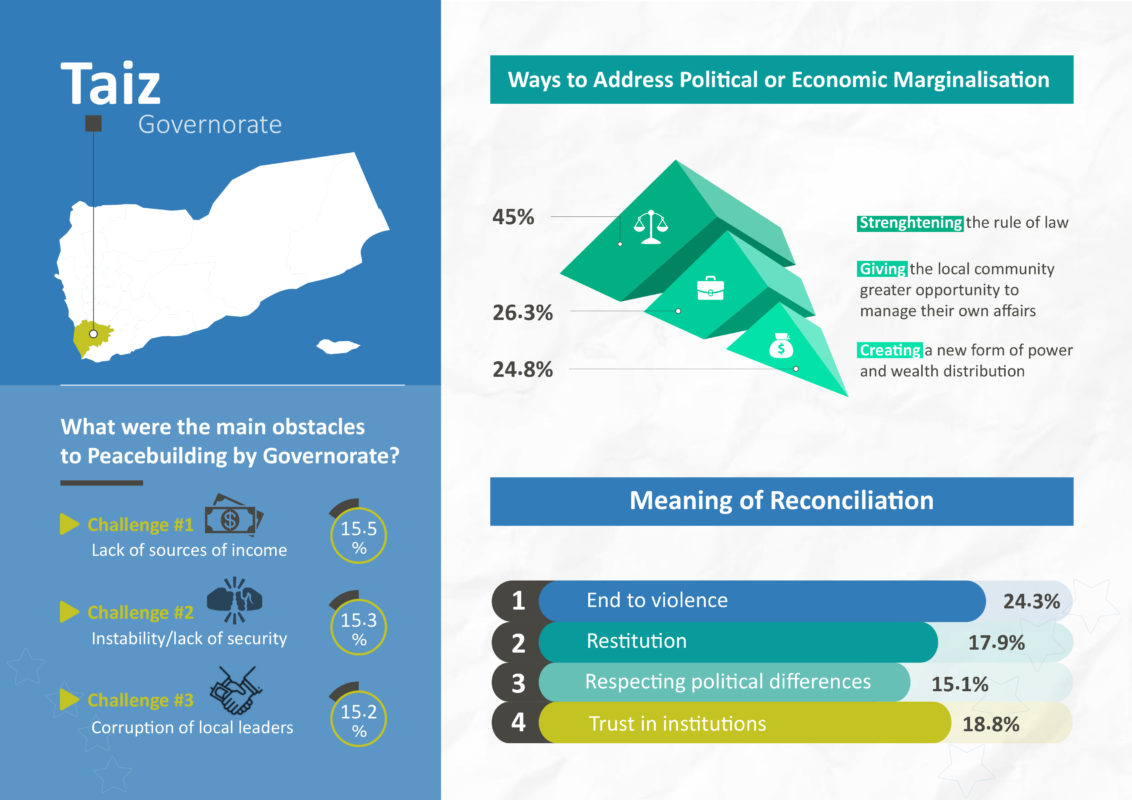

Al-Maharah

Al-Maharah has experienced less violence during the conflict than other governorates. Due to its geographic position, it is a focal point in ongoing regional rivalry between Saudi Arabia, UAE, Qatar and Oman, each of which seeks to entrench its influence. Since the 2015 outbreak of the Yemeni conflict, Al-Maharah has remained predominantly under the control of the IRGY led by President Hadi, although it is currently governed with heavy influence from Saudi Arabia. Tribes in the governorate adhere to a code of conduct that historically helped mediate disputes and contain conflict. Regional competition for influence, however, has threatened the stability of this otherwise relatively stable part of the country.

Al-Maharah is the second-largest governorate in Yemen but is also the least populated. Nearly half of the population (250,000 of 650,000) are internally displaced persons (IDPs) from all over the country. Deteriorating basic services and dwindling resources are further increasing the number of people who need assistance. During the consultations, participants repeatedly complained that the influx of IDPs is leading to demographic changes, straining local resources, and contributing to rising tensions within the local community.

While there was no active fighting during the consultations in Al-Maharah, a government-issued circular banned meetings and crowds to curb the spread of Covid-19. This made it more difficult to engage participants across the targeted districts. Furthermore, due to the scarcity and pricing of internet connectivity, as well as low technical capacities, a team member had to travel there and organise a hybrid community dialogue conference in Al-Ghaydah.

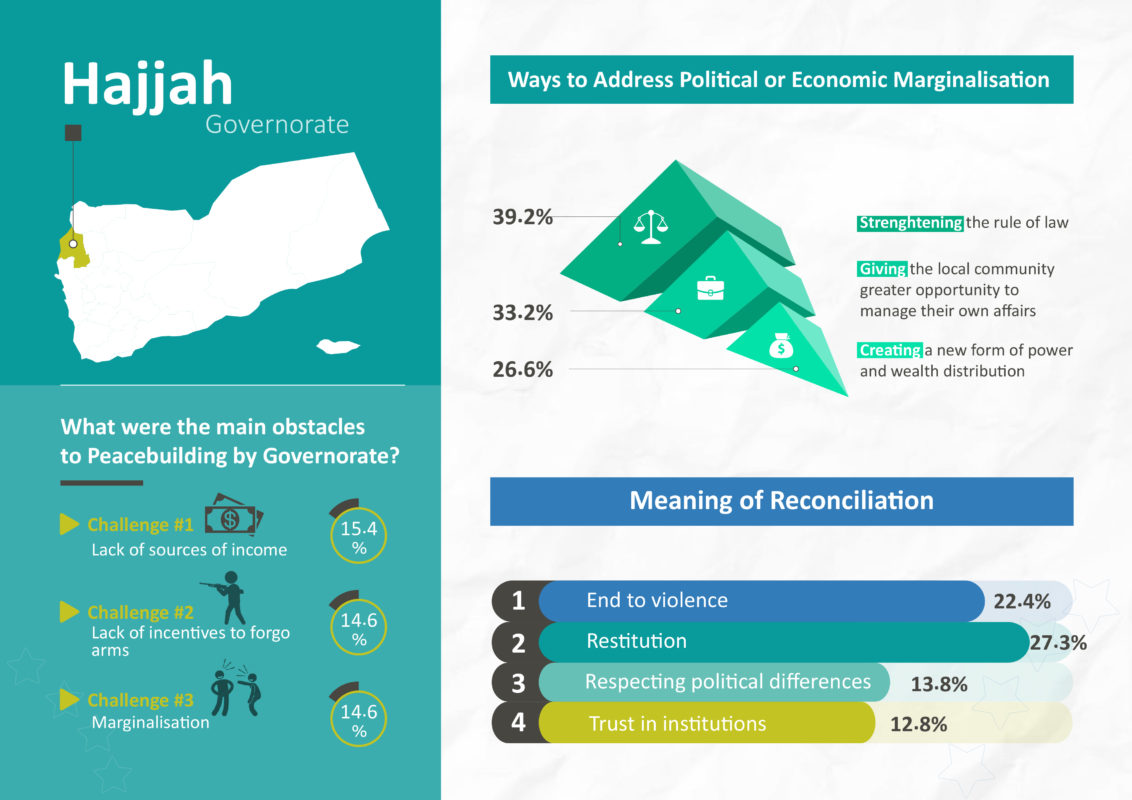

Hajjah

Situated north of the capital Sana’a, Hajjah is one of the governorates most affected by the conflict. It has experienced increasing violence since 2015 due to the expansion of the Houthi movement. Though some tribes in Hajjah oppose the Houthis, the latter were able to consolidate control over large swaths of the governorate and crush pockets of resistance through military power and financial incentives provided to some tribal leaders. Hajjah is strategically important to the Houthis as it is adjacent to their main stronghold in Sa’ada, the Red Sea, and part of the coastal and strategic Al-Hodeidah governorate.

Hajjah has an estimated population of 2.1 million people, 91 per cent of whom live in rural areas. Since it borders Saudi Arabia, it serves as a station for human trafficking, and is affected by the widespread smuggling of Yemenis and African refugees. Ongoing hostilities have had a major humanitarian impact; nearly half the population is in crisis according to the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification released in December 2019, and 28 of the province’s 31 districts are in a state of emergency. Crossfire between the two sides has also prevented families from travelling between districts to receive humanitarian assistance.

The field work in Hajjah was challenging due to security concerns related to the travel of the researchers and the large size of the governorate. Matters were further complicated by the scarcity of resources and internet access. Nevertheless, the local teams were able to slowly conduct consultations in six districts, the largest number of any governorate in the study.

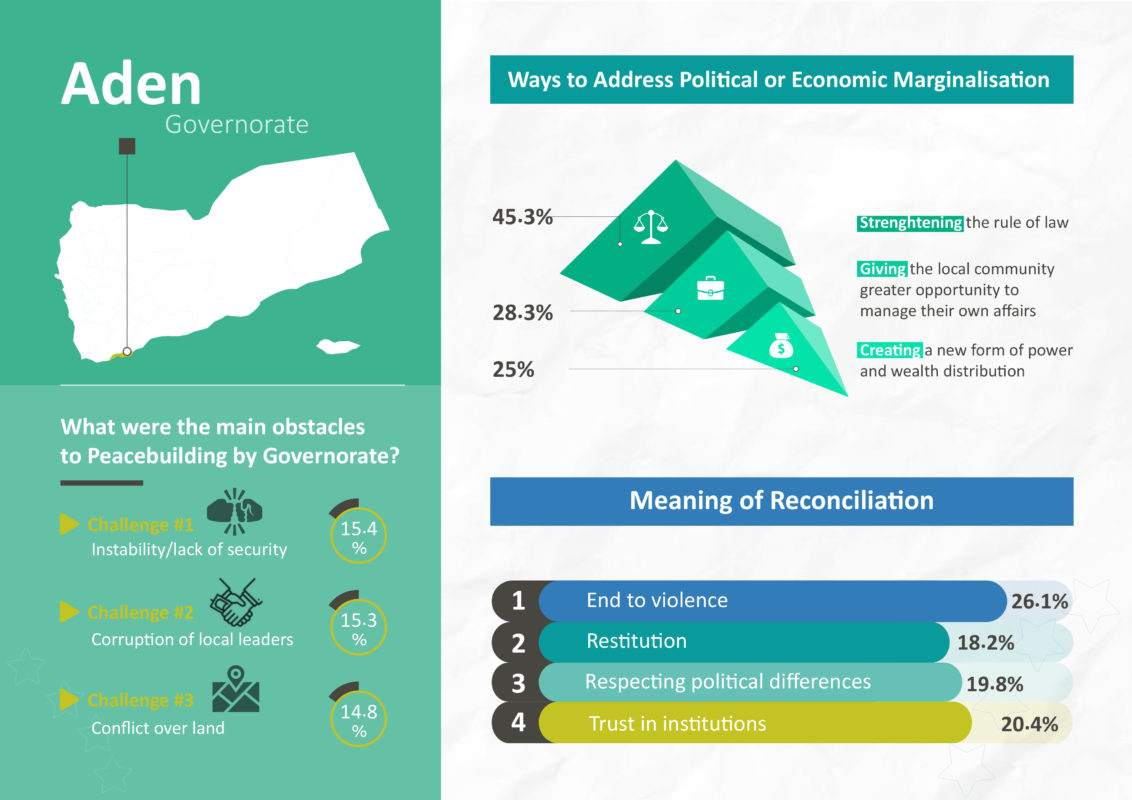

Aden

Aden, with approximately 850,000 inhabitants, is located in the southwestern tip of Yemen on the coast of the Gulf of Aden and the Arabian Sea. After Sana’a, it is the most politically and economically significant governorate. It is home to the Port of Aden, one of the country’s main ports, and for two decades was the political capital of what was then the People’s Democratic Republic of Yemen.

In March 2015, the Houthis, then allied with former President Saleh, invaded Aden weeks before President Hadi declared it the temporary capital. In July 2015, the Popular Resistance Forces, with the support of the Saudi-led coalition, expelled the Houthis from Aden. Shortly afterwards, the interests of the IRGY camp and the southern forces demanding secession collided, leading to the official creation of the STC in 2017. The IRGY attempted to assert its authority over the STC for a short period of time before the latter took full control and pushed the IRGY out of Aden in January 2018. In 2019, Saudi Arabia facilitated reconciliation efforts between the IRGY and the STC, and the Riyadh Agreement was signed. Its provisions include the creation of a power-sharing government between president Hadi, the STC and other southern Yemeni political forces, the joint appointment of state officials in the southern governorates, and the amalgamation of both sides’ military forces. Since its signing, progress on the Riyadh Agreement has stalled on multiple occasions; it remains only partially implemented.

The IRGY recently returned to Aden in the hope of completing the implementation of the agreement. However, mistrust and tensions have continued to rise between the two parties. Amid these disputes, Aden is experiencing a deterioration of services, especially electricity and water cuts, a deteriorating health sector, the spread of insecurity due to the presence of armed militias, frequent armed clashes, and economic decline.

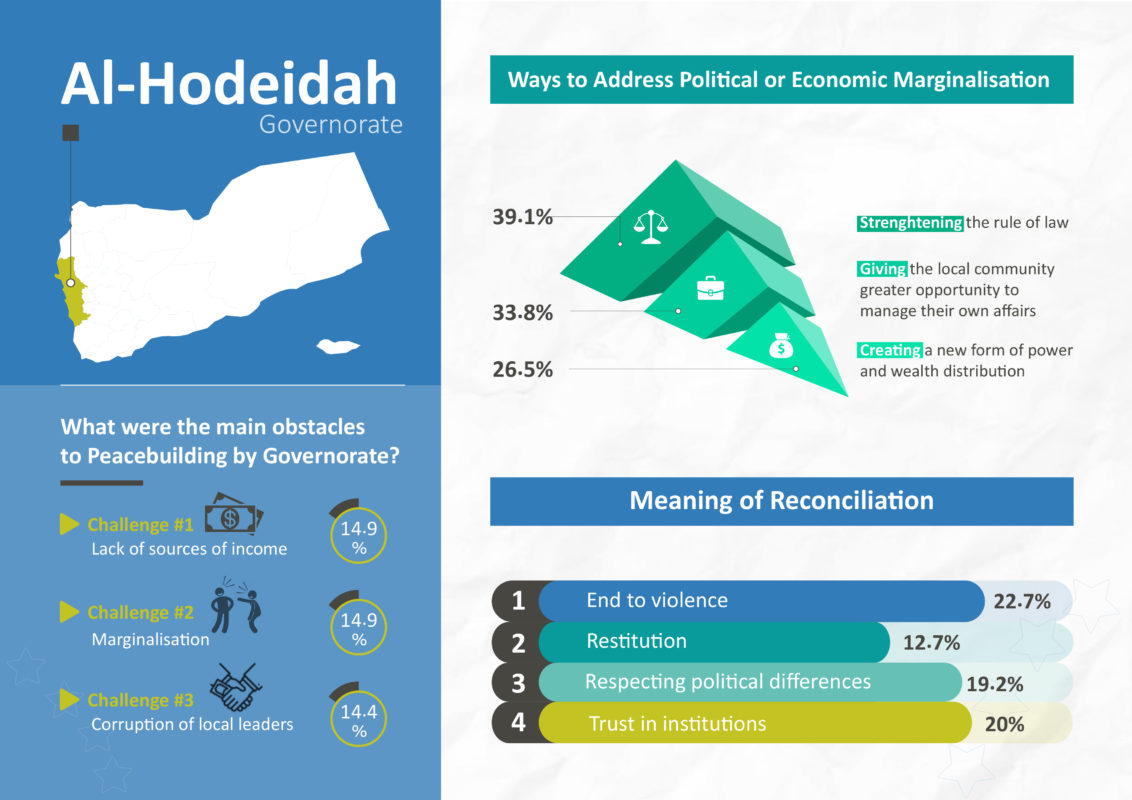

Al-Hodeidah

Al-Hodeidah is considered one of the most important northern Yemeni governorates due to its strategic location on the coast of the Red Sea and a population of approximately 3 million. It is one of the wealthier governorates, rich in marine, livestock and agricultural resources. Although often referred to as Yemen’s ‘food basket’, its people live in extreme poverty for a number of reasons, including financial mismanagement and heavy centralisation. Most of those who control land and resources in Al-Hodeidah are public officials appointed from elsewhere; locals see themselves as marginalised.

In October 2014, the Houthis took control of Al-Hodeidah, in part because the governorate is home to one of northern Yemen’s most important seaports – which has generated revenues that have been used to finance the Houthis. Al-Hodeidah’s strategic value also derives from its proximity to international shipping lanes in Bab al-Mandab – one of the most important global trade corridors. In 2018, the IRGY, supported by the Saudi-led coalition, launched a large-scale military operation to recapture Al-Hodeidah and its strategic port from the Houthis. However, after taking control of large areas along the western coastal strip, passing through the strategic Durayhimi district (the southern gateway to the city of Al-Hodeidah), the international community intervened to end the military campaign, fearing it would lead to shutting the seaport through which most aid to the country passes, and that it would exacerbate the humanitarian crisis. The Houthis and the IRGY signed the Stockholm Agreement in Sweden in December 2018, which formally ended the fighting and the IRGY military campaign, but light skirmishes and flare ups between the two forces continue at the time of writing.

The FSO Safer, a rusting oil storage facility off the coast of Al-Hodeidah, is another cause for major concern for the governorate and Yemen at large. The tanker, which has had little or no maintenance for years, is on the verge of leaking and causing an environmental catastrophe. Estimated to hold 1.14 million barrels of crude, a leak from the tanker could spill four times the amount of oil leaked by the Exxon Valdez. Yemen has no capacity to deal with such a leak, and aside from the huge environmental cost, the port through which much of the aid is coming would most likely be shuttered.

Operating in Al-Hodeidah was exceptionally difficult because the territory is highly contested. Researchers were treated with suspicion, and there were multiple checkpoints and landmines. Although the researchers took several precautions, one local team member narrowly avoided a landmine (indicative of the general difficulties encountered when traveling by car in some locations), and another was briefly detained for questioning.

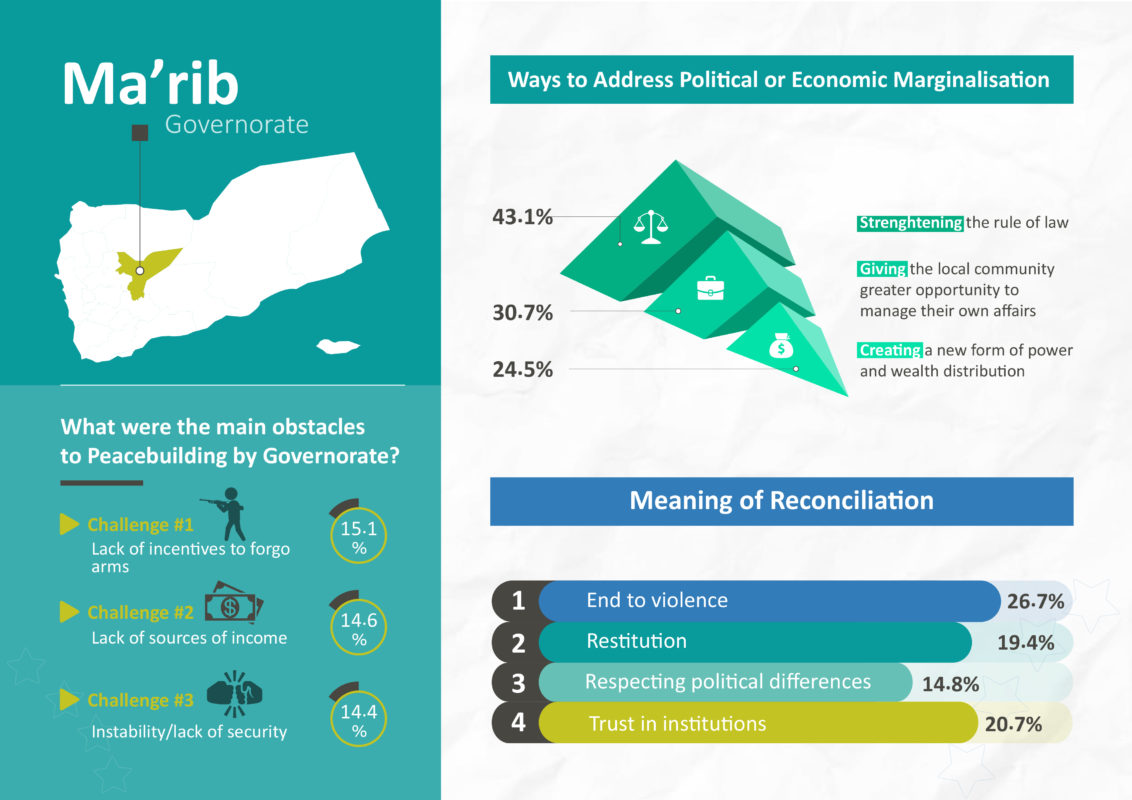

Ma’rib

For the past 6 years, the centrally located governorate of Ma’rib has been the last remaining IRGY stronghold in northern Yemen. Over the course of the conflict, Ma’rib has experienced relative stability with the exception of sporadic fighting between the Houthis and the Saudi-backed coalition when the group repeatedly attempted to capture the governorate. Since January 2020, however, the Houthis have significantly intensified their efforts to capture the strategic governorate.

Ma’rib has an estimated population of over 2 million, more than half of whom are IDPs. The strong tribal identity in Ma’rib has been a major factor in regulating society in the absence of effective support from the central government. Local authorities in the governorate comprise tribal leaders and officially appointed staff aligned with the IRGY. As such, it has a relatively unique and effective decentralised model of local governance bolstered by the unity of the population, tight-knit security and economic resources.

Ma’rib is more self-sufficient than many other governorates and has better access to basic services and resources, partly because it was spared from much of the fighting and disruption during the war. It also enjoys a degree of financial independence. Unlike other governorates, it has exclusive control over the Ma’rib branch of the Central Bank (with no oversight from Aden) and manages to retain income from oil and gas sales as well as the Al-Wadiyah border crossing.

During the consultations, the Houthi assault on Ma’rib had just intensified. There were intermittent disruptions in internet connectivity, which led to operational delays and communications difficulties with the local teams and interfered with their ability to upload the raw data from the field work. Moreover, security measures were tight, and even though permits for the consultations were produced, a member of the team was interrogated (but came to no harm).

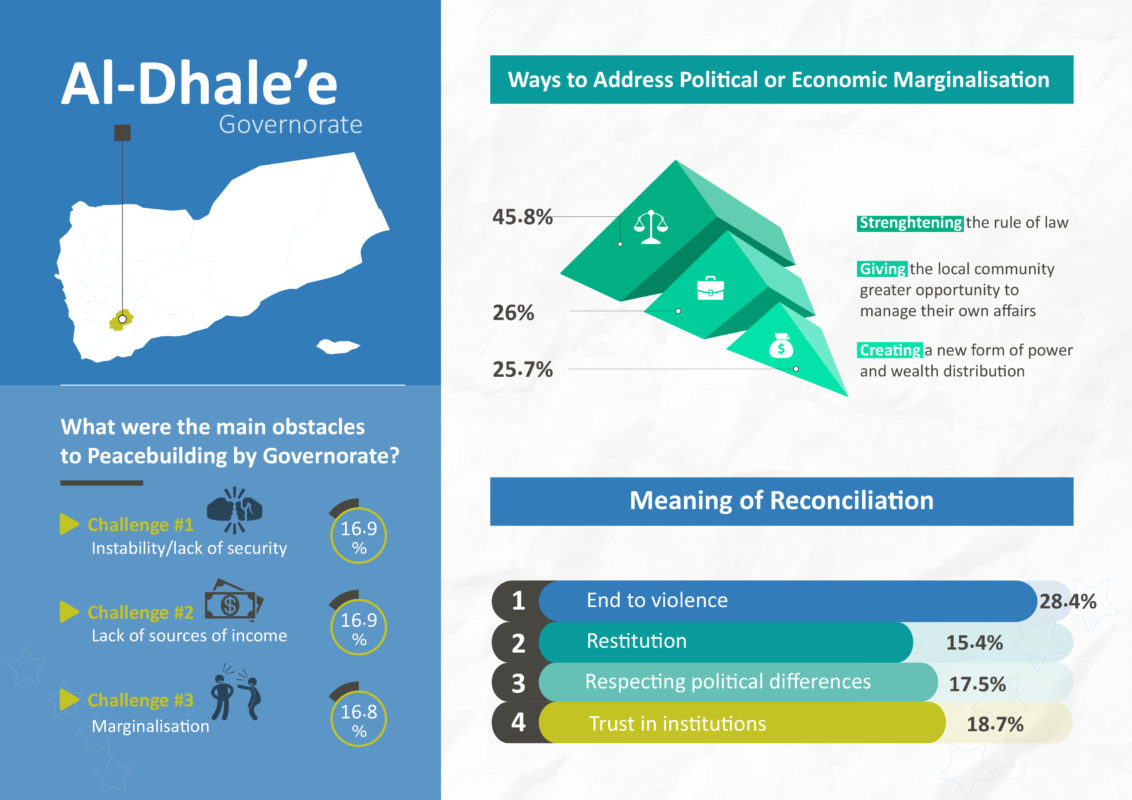

Al-Dhale’e

Al-Dhale’e was created after the unification of the country in May 1990. It was created by combining border districts of both former Yemeni states (North and South). However, it played an important role in balancing unity and some southern demands for secession, which began to appear more clearly after the 1994 civil war and the emergence of the Southern Movement in 2007. With a population of about 800,000 people, Al-Dhale’e has a high density and is known for its polarised local dynamics.

Historically, Al-Dhale’e has represented one corner of the triangle of military power in the South (Al-Dhale’e, Yafa, Radfan). In the past, the former President Saleh’s regime was keen to use force to silence the governorate and its escalating demands to secede from the North. The violent military leader, Abdullah Dabaan, exercised remarkable repression which reinforced negative attitudes towards unity. In 2015, as the Houthis advanced towards Aden, Al-Dhale’e became a target and a transit point, but they were successfully repelled towards the North early in the conflict. However, the Houthis still pose a serious threat to several areas of Al-Dhale’e, with continuing clashes and attacks in an attempt to invade the governorate again.

Security was a concern during the field work in Al-Dhale’e due to the roadblocks and proximity to clashes between the Houthis and IRGY.

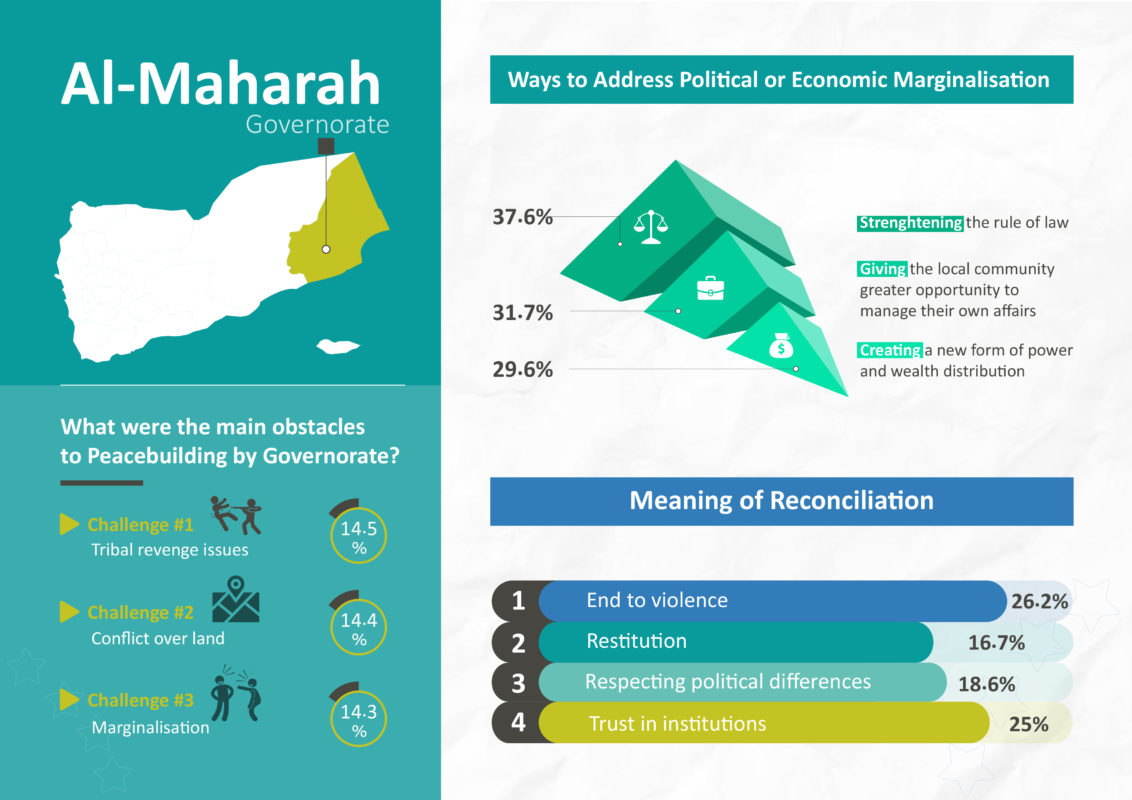

Sana’a

Sana’a has been an embattled city within Sana’a governorate since the escalation of the conflict in early 2015. It has witnessed three major battles (in 2011, 2014 and 2015), and was intermittently targeted by airstrikes and other ground attacks resulting in tremendous loss of human life and widescale material damages. In September 2014, the Houthis entered Sana’a and within months gained control over most of the governorate. Historically, Sana’a has been a main destination for IDPs, many of whom left rural areas due to a lack of jobs and climate-related factors like water scarcity and droughts.

According to OCHA, there are nearly 1.1 million people in need of assistance in the governorate, which constitutes approximately 80 per cent of its population. The conflict has caused significant damage to health facilities; the remaining facilities have too few health workers and many patients coming from neighbouring governorates, leading to strained capacities. The closure of Sana’a airport to all commercial flights in August 2016 prevented those in need of specialised medical care from seeking assistance abroad.

The biggest challenge associated with the field work in Sana’a was the fear of arrest and interrogation. However, the team ensured a smooth flow of local consultations by securing permits ahead of time.