The Kurdish-majority city of Kobane became front-page international news in 2014 when ISIS fighters, fresh off a victorious campaign sweeping across Iraq and Syria, besieged the city for months. In what would become a major turning-point in the war against ISIS, predominantly Kurdish forces managed to break the siege on Kobane and push back ISIS fighters away from the city. However, the human cost of Kobane’s local conflict—characterised by siege, artillery barrages, and massacres—was tremendous.

Kobane before the conflict

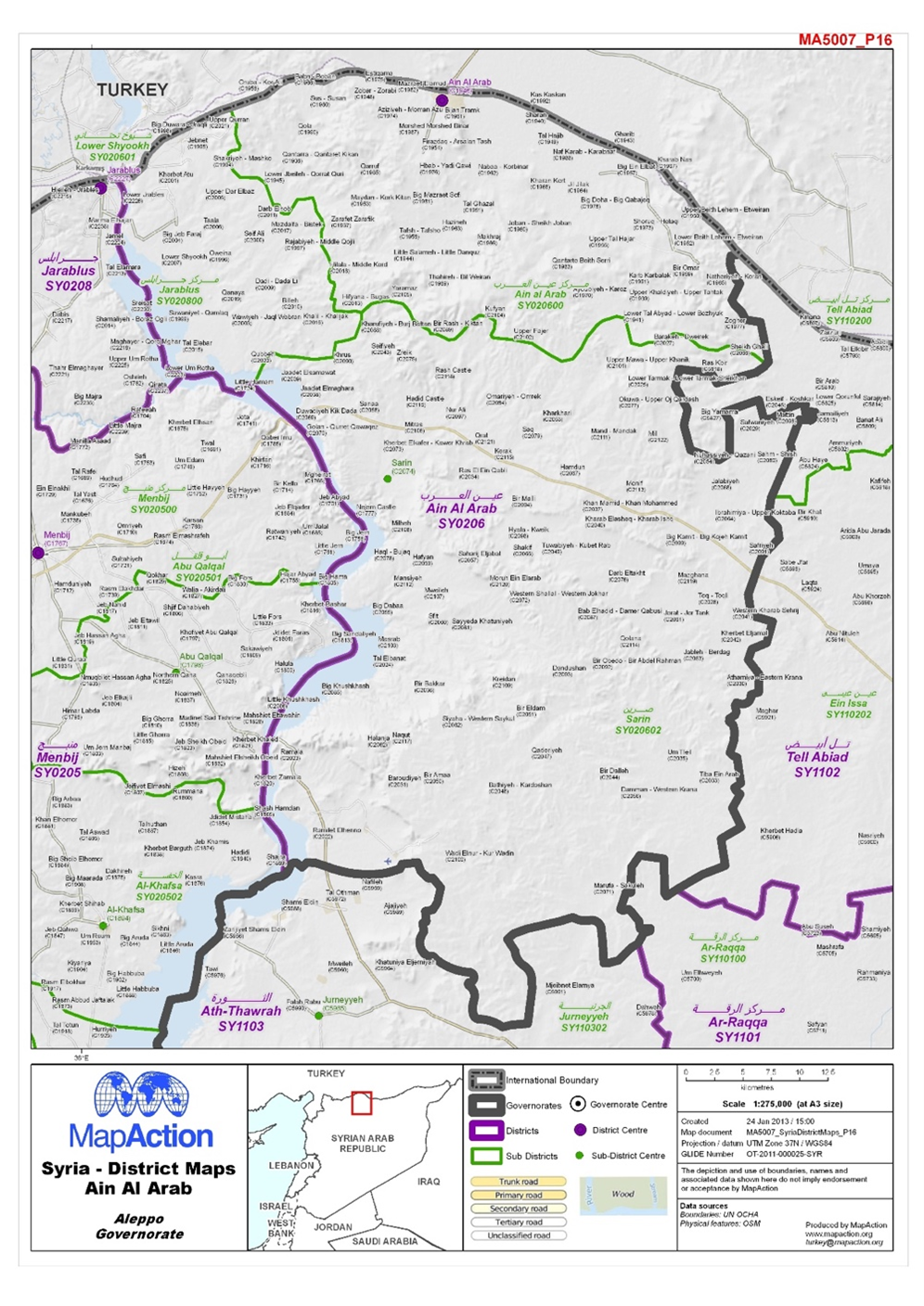

Located on the border with Turkey in Syria’s agricultural heartland, the city of Kobane—officially, but less commonly, known by its Arabic name, Ain al-Arab—lies on the Suruç (Suruch) Plain approximately 30 kilometres to the east of the Euphrates River and about 150 kilometres northeast of Aleppo city. The district’s total population stood at approximately 450,000, 95% of whom were Kurds living alongside Arab, Armenian and Turkmen minorities. Syria’s 2004 census counted some 192,500 people living in the Kobane central, al-Shuyoukh and Sarrin sub-districts.[1]

Kobane’s name is derived from the word “company,” a reference to the German Railway Company that built part of the Konya-Baghdad Railway in 1911.[2] Although the city was first founded and built in 1892, it was through the construction of the Baghdad Railway Project between 1911 and 1912 that it became an important settlement. The German company extracted black stones from the nearby Mashta al-Nour hill and used them to extend the railway between Berlin and Basra in Iraq. This railway line was later transformed into the border between Syria and Turkey. After the formation of the modern Syrian state, Kobane was considered part of Aleppo province.

After the collapse of the Ottoman Empire, Armenians fleeing massacres (recognised by many states as the Armenian Genocide) sheltered near Kobane’s railway station, and this community would go on to coalesce into a village after 1915. The demarcation of the border with Turkey along the railway line, a product of the modern colonial borders drawn up through the Sykes-Picot Agreement, left part of the city on the Turkish side. Nowadays, this is called Mürşitpınar (Murshid Pinar) village, which is home to a border crossing between the two countries.

Much of the city planning of Kobane was carried out by French Mandate authorities during France’s occupation of Syria; some of the French-style buildings still exist, and the city has wide and straight streets constructed in grid-plan style like a chessboard. The Big Mosque, built in 1957, was one of the city’s most important monuments, although there are also Catholic, Orthodox, and Armenian churches in Kobane, despite the fact that most Armenians re-emigrated to the Soviet Union in the 1960s. Kobane was previously divided into five large neighbourhoods including Kaneh Murshid in the northwest, Kaneh Arban in the northeast, as well as Big Bhutan, Maktaleh, and the Old Canal.

Figure 1: Kobane (Ain al-Arab) district in Aleppo governorate.[3]

The Kurdish community in Kobane is tribal, with strong customs and traditions. There are several Kurdish tribes in Kobane that are strongly associated with Kurdish tribes on the Turkish side of the border. Many families are big, consisting of, on average, seven people, something attributable to tribal customs but also agriculture being the predominant mode of production in Kobane and the surrounding area. Youth make up the majority of Kobane’s inhabitants.

Historically, Kobane was primarily an agricultural society. Its arable soil, water abundance and moderate climate—characterised by a combination of heat, rain, and humidity—supported agriculture well. Initially, the region was particularly known for cereals such as wheat and barley; later, people started cultivating industrial crops such as cotton in addition to legumes and vegetables. Kobane has high-quality natural trees as well as fruit trees. The population also has a culture of animal domestication that dates back hundreds of years. Traditionally, there was little interest in professional jobs and crafts. The Armenians who came to Kobane were professionals famous for their work in industry, most notably digging artesian wells and other tradecrafts. When many Armenians left the city in the 1960s—migrating to the Soviet Union instead—it became readily apparent that Kobane lacked skilled workers in the industries that the Armenians left behind. Over time, Kobani residents gradually assumed these professions, eventually becoming key contributors to production and expertise.

The eastern regions of Syria—the areas located east of the Euphrates, including Kobane—were long looked down upon by Syria’s urban elite as “developing areas” that primarily provided essential materials such as agricultural goods, vegetables, oil derivatives, gas and electricity to “developed” coastal and inland areas around the capital, Damascus. Northeast Syria ranked among the most deprived areas of the country in terms of access to basic services, including healthcare and education.

There were also severe political and security constraints meted out by central authorities: like many regions of Syria, Kobane suffered from pervasive surveillance following the various coup d’états that rocked Syria in the mid-20th century and culminated in Hafez al-Assad’s military takeover in 1970. At the same time, Kobane, like other Kurdish-majority areas, experienced an additional dimension of systemic marginalisation in the years leading up to the outbreak of the Syrian uprising and ensuing conflict.

‘Policy of exclusion’: Anti-Kurdish repression in Kobane

After Syria’s independence from French occupation in 1946, Kurdish areas of the country were systematically marginalised by authorities in Damascus.

The so-called “Hasakeh census,” carried out in October 1962 by Syria’s “separatist” government in Kobane and Hasakeh,[4] required Kurds to prove that they had lived in Syria since at least 1945, in addition to their ancient historical presence in the region; otherwise, they would lose their Syrian citizenship. Many complained that authorities did not give sufficient information about the process or time to prepare documents. Effectively, the census divided Kurds into three categories: those able to prove Syrian nationality; those without nationality but who were registered in the official civil registry as ajanib (foreigners); and those in an even more precarious situation, without nationality or registration, who became known as maktoumeen al-kayd (unregistered). As a result, 120,000 Syrian Kurds—20% of the total Kurdish population in Syria—were deprived of Syrian nationality as well as civil and political rights,[5] an issue that impacted future generations for decades and that successive Syrian governments failed to resolve.[6] International human rights groups as well as Kurds themselves, many of whom were left stateless because of the census, saw it as a discriminatory measure meant to deliberately target Kurds in Kobane and Hasakeh.

Statelessness became hereditary. By 2011, the number of ajanib registered with the Civil Registry Directorate had reached 346,242 people.[7] Whereas the ajanib were at least registered and issued with a “red card,” a semblance of civil status, the maktoumeen were worse off, possessing neither nationality nor registration. As children of maktoumeen themselves became maktoum, the number of people affected only increased over time. Relying on the records of local mukhtars (community leaders), officials estimated that there were more than 171,300 maktoumeen before the 2011 uprising and conflict.[8] By the time protests started spreading across the country after March 2011, President Bashar al-Assad sought to appease Syria’s Kurdish communities by granting citizenship to those registered as ajanib through Decree 49/2011.[9] Officials estimated that, by May 2018, the number of ajanib who obtained citizenship had reached 326,489, while 19,753 had not. Some maktoumeen were also able to obtain citizenship after rectifying their legal status, but many—presumed to be well over 100,000 people—remained without registration.[10] Assad’s proposal was a plaster on deep wounds that proved too little, too late for a Kurdish population that had suffered five decades of political, economic, and social discrimination and exclusion.

In general terms, the Syrian government ruled Kurdish-majority Kobane with an iron fist, conducting arrests and restricting any space for Kurdish political activism as well as expressions of Kurdish identity, property ownership and educational rights. Authorities often refused to officially register people with their Kurdish names, although this did not stop families from using these names in everyday life. One interviewee, who lived in rural Kobane, recalled how:

It was even forbidden to name our children when they were born with a Kurdish name. Our village was [administratively] part of Sarrin [a town south of Kobane]. At the time, the employees in the civil registry were Arabs; they mocked us and our names and refused to register us. We were forced to give our children Arabic names instead.[11]

The authorities also changed the historic Kurdish names of hundreds of villages, towns, hills and other sites across Kobane and the rest of northeast Syria, replacing them with Arabic names. Kurdish music and songs were prohibited, and authorities prosecuted those who commemorated Nowrouz, the Kurdish New Year celebration, and other Kurdish holidays.

The issue of property and land ownership was especially sensitive. Decree 1360/1964 designated a 25-kilometre strip of land along the Syrian-Turkish border as a “border area,” within which Kurdish ownership was restricted. The interviewee from rural Kobane considered this part of the regime’s broader discrimination against Kurdish communities:

The regime did not allow landlords and Kurds to register their property under their names. They used their political logic to justify this. Unfortunately, many Kurdish families in Kobane have no civil record and are treated as ajanib. However, we have called for our human and intellectual rights and suffered from a lack of support and assistance that we needed. No one has spoken about why we were deprived of our liberties or our mother tongue.[12]

Later, in 2008, President Bashar al-Assad built on this by passing another decree that subjected all properties in the border areas to security permissions.[13] This prevented the sale and purchase of land within the border area until a security approval had been obtained, in practice significantly limiting the possibilities for Kurdish ownership as permits were more easily granted to Arabs than Kurds. The law also prohibited the registration of properties for Kurds in both Raqqa and Tal Abyad.

Kobane faced economic marginalisation, as well. Many suffered from poverty, with little to no development projects undertaken in the region and no support given for farmers or youth groups in Kobane. There were few factories or agricultural development projects undertaken in the area by the central authorities. Despite the proximity of the Euphrates River to the city, Kobane district lacked drinking water at the same time that the Syrian government established extensive irrigation channels to Arab towns and villages hundreds of kilometres from the Euphrates. Kobane would have electricity for just a few hours per day. People resented being forced to pay taxes to the government despite poor services.

As a result, many young people, and especially those with high qualifications, migrated due to the lack of employment opportunities. This caused a brain drain. One inhabitant of Kobane detailed the difficulties:

There were no jobs and no economic projects. When we were trying to launch a project, they presented obstacles and gave us excuses. You couldn’t build a factory or launch a project if you weren’t able to dig a water well on your land. All these pressures on the area were designed to displace its people and residents. There was internal and external migration of the region’s population to the Arab Gulf, North African countries, and other countries such as Lebanon and Iraq. In each household, there was one or more person who had gone abroad.[14]

Education in Kobane followed the Syrian government’s curriculum, under which the teaching or even speaking of the Kurdish language in classrooms was forbidden.[15] In fact, instruction in the Kurdish language was considered a punishable offence, and teachers and staff from other areas of the country were brought to teach in the district—except for a small proportion of Kurdish teachers who were required to join the Ba’ath Party before being allowed into classrooms.

Many Kurdish children encountered difficulties at school because of the language barrier: learning Arabic was difficult because many parents often spoke the language poorly. Authorities’ neglect or politicisation of the education system made matters worse: classes were overcrowded, sometimes with as many as 40 students per classroom, while the state curriculum was developed in line with the Ba’ath Party’s heavily militaristic ideology. This trend was more pronounced in Kobane’s villages; not every village had a school building, meaning pupils were forced to travel to villages with schools. These factors all resulted in higher dropout rates among children who instead went to work in industrial or manual jobs.

Kobane’s health sector also suffered from neglect. There was no public hospital in the city and only one vaccination clinic. Shortages of medical staff meant there was just one general practitioner and one nurse, in addition to a private hospital called the Alloush Hospital, serving more than 450,000 people. Otherwise, patients with difficult conditions in need of specialised care were required to travel long distances to Aleppo or Damascus for treatment.

“The Syrian government imposed a policy of exclusion on our areas for decades,”a villager from the Kobane countryside said, adding that:

There were no services in Kurdish areas, with no exceptions. Even at the level of healthcare, there were no services in Kobane at that time. There was no education in the Kurdish language. The roads leading to the villages were not paved; they were just dirt roads. We [lacked] elementary, primary, or secondary schools. Even drinking water wasn’t provided by the government.

I am not only talking about my village, Barkh Botan, but also about Kobane and its villages. They treated us as a colony, as prisoners with no value. Even the mukhtar used to […] rule over us. He was the authority. We were not able to discuss things with him or ask for our rights.[16]

As is often the case, the effects of this system were not equally felt across the population; women often had a more challenging time than men. One woman interviewed said:

In the past, women suffered and had no rights. In terms of education, for example, women could not study because of tribal constraints. Under the Ba’ath regime, it was difficult to send our daughters to cities such as Aleppo, Manbij and Damascus for university because of the lack of security. Few girls from the city would study at the university. In villages, it was considered shameful for a girl to go out. When Kurdish women went to Aleppo in their traditional Kurdish dress, they were mocked.[17]

Since the early days of the regime, the relationship between the central government in Damascus and the Kurds has been tense, leading to recurrent protests and unrest in Kobane and other Kurdish-majority areas, as well as arrests and assassinations targeting Kurdish leaders and activists.[18] Tensions increased over time, however. In 2004, tens of thousands of Kurds took to the streets in Kurdish cities as well as Aleppo and Damascus following a flare-up that started at a football match in Qamishli. During the so-called “Qamishli Uprising” that followed, Kobane, like other Kurdish-majority cities, revolted against the Syrian government and drove security forces out of the city.[19] In response, the Syrian government sent in military reinforcements, arresting and imprisoning hundreds of mostly young men for years at a time—some of them are still missing to this day. Hundreds of Kurdish students were arrested at campuses around the country, while others were dismissed and expelled from universities altogether.

The conflict in Kobane

The situation in Kobane was already tense before the Syrian uprising broke out in March 2011, but quickly escalated as the uprising turned into an armed conflict and dozens of armed groups emerged across the country.

On 19 July 2012, the YPG took control of security buildings and government institutions; Kobane was declared “liberated” and renamed the “Canton of Kobane.”[22] Many in Kobane saw this as a success for the Kurdish popular movement that, for years, had demanded changes to the political and living conditions in the district and reiterated the fundamental rights and freedoms of the Kurds. Shortly afterwards, the PYD formed service structures in the area—structures that would form the backbone of the Autonomous Administration, or AANES, later in the conflict.

Kurdish-majority areas of northeast Syria were no different, although the pace of militarisation was slower. People were initially unwilling to take up arms. In late 2011, the Supreme Kurdish Committee, comprising the Kurdish National Council (KNC) and the PYD, was formed.[20] Joint military checkpoints were set up by Kurdish parties to protect Kurdish areas, and the PYD soon after announced the formation of a military wing under the name of the People’s Protection Units, Yekîneyên Parastina Gel (or YPG).[21]

Several armed opposition factions fighting regime forces—ranging from the FSA to more Islamist groups such as Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham and Liwa’ al-Tawheed—challenged the YPG’s control over the area under its control. In Kobane, there were sporadic but recurrent clashes between the YPG and Islamist groups including Nusra.[23] Armed opposition factions sought to seize Kobane and imposed a siege on the city from the east, west and south, with the Syrian-Turkish border acting as another boundary to the north. As part of the siege, opposition factions completely blockaded roads leading into and out of the city, besieging more than half a million Kobane residents and IDPs who fled ongoing military conflicts in Damascus, Dera’a and Homs. Water, electricity and food supplies to the city were cut off. Civilians bore the brunt of the violence: armed groups targeted civilians with kidnappings for ransom, while armed groups repeatedly sent car bombs into the city.

The arrival of ISIS

In late 2013 and early 2014, ISIS emerged as a major player in the Syrian civil war. Soon after splitting from Nusra and declaring its self-proclaimed “caliphate” covering areas of Iraq and northeast Syria, ISIS began preparing to attack Kurdish areas—including the countryside of Hasakeh and Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain, where it faced opposition from the YPG and its female counterpart, the Yekîneyên Parastina Jin (Women’s Protection Units, or YPJ). The city had long been in ISIS’ crosshairs, in part because the YPG’s headquarters were in Kobane. A victory in Kobane would allow ISIS to cleanse the Kurdish population, spread into other Kurdish areas and assert control over the Syrian-Turkish border to secure the group’s western flank as well as the passage of foreign fighters and logistical supplies.

ISIS’ advance came from the south-west. On 13 March 2014, ISIS took control of the Qere Quzak bridge connecting areas east and west of the Euphrates between Kobane and Aleppo. Making use of heavy weaponry seized from Mosul in the summer of 2014, on 2 July 2014 ISIS seized the village of Zour Maghar, located west of Kobane, overlooking Jarablus.[24] Following partial defeats in Hasakeh around Jaza (Ceza) and Rabia and having been pushed back from the Sinjar mountains in Iraq, ISIS then regained its strength and headed to Kobane.

The full-scale assault on Kobane started on 15 September 2014, when ISIS launched a three-pronged attack on the city. Repeating the pattern of the earlier siege, it attacked the city from the east, west and south,[25] while ISIS fighters deliberately cut off water and electricity prior to their attack.[26] YPG fighters evacuated residents from front-line neighbourhoods as well as 400 villages in the Kobane countryside.[27] Many of those who were too old, sick or disabled to flee, or those who chose to remain, were executed by ISIS in villages such as Pinard, Tal Shaer, Kortek, Qaramou, Tal Haidar, Dongez and Biliq.[28] Mass casualty incidents became a mainstay of ISIS’ offensive on the city.

When ISIS fighters arrived at the outskirts of the city, residents fled north and entered Turkish territory near the border crossing with Suruç. Civilians and fighters who stayed behind faced unimaginable levels of violence. Indiscriminate shelling by ISIS caused huge civilian casualties.[29] Between 15 September and early November 2014, large numbers of ISIS fighters were killed, but hundreds of YPG and YPJ fighters also lost their lives in defence of the city. On 13 October 2014, ISIS conducted a triple suicide bombing, including one explosive at the border crossing at 2.00 am. Although the YPG repelled some of the attacks, ISIS by now controlled around half the city.[30]

In the following weeks, however, the tide seemed to turn. While various car bombs continued, the US-led Global Coalition against Da’esh commenced airstrikes in early October and with increased air support, Kurdish fighters pushed back ISIS. ISIS was deemed to be “retreating” from parts of Kobane.[31] Then, in late October 2014, with ISIS threatening its immediate border, Turkey permitted a convoy of Peshmerga forces from the KRI to cross Turkish territory to arrive in Kobane with heavy weaponry in tow.[32] ISIS continued its high-intensity attacks, including the detonation of more than 63 car bombs in Kobane, as the group sought, unsuccessfully, to break the Kurdish resistance.

‘Everyone suffered’: Forced displacement and arbitrary arrests

During ISIS’ assault on Kobane, Kurdish forces hastily evacuated most of Kobane’s outlying villages. More than 200,000 civilians poured across the Turkish border to Suruç.[33] Those who fled left behind all their possessions and were forced to cross minefields planted near the Syrian-Turkish border; dozens of women, children and the elderly lost their lives as a result of landmine explosions, while others lost limbs or suffered other serious injuries.

A refugee who took this treacherous route into Turkey remembered the ordeal:

Everyone went to the border area. It was a heavy burden […] especially for those in charge of their families; those who had elderly people, disabled people and children with special needs [with them] also suffered a lot. Some carried their elderly mothers or fathers on their backs and crossed the border. The situation was catastrophic.

Everyone suffered. The mines in the border zone claimed the lives of [many] civilians. Now and then, a mine would explode, [killing] women, children and the elderly. Sometimes mines would explode while cars were trying to cross to the other side.

The border crossings that were open at the time were in the village of Marj Ismail on the eastern side [of Kobane] and Tal Shaer to the west. Everything was in front of us. The Turkish army was blocking the entry of livestock and cars into Turkey. People became confused. Many people stayed at the border strip because of their livestock and cars.

After entering Turkey, families went to various places to work or went to refugee camps. Life for those displaced at the border strip was full of trouble and misery. People stayed outdoors. People went out of their towns and left everything behind.

While you were trying to go out, you’d look behind to see thousands of people [behind you]. You’d hope that nothing would happen to your town so that you could go back again. This was what was going on in the minds of every displaced person.[34]

One displaced woman recalled how people decided to escape ISIS to the Turkish border only when conditions became untenable during the ISIS-imposed siege:

ISIS attacked us with heavy weapons. [We were] forced to seek refuge. Before that, we were under siege. People were preparing food on firewood. We had no gas bottles or electricity. I turned an empty margarine can into a bucket to get water out of the well [because] there were no buckets for sale. We wish we had stayed in those conditions rather than resorting to Turkey.[35]

In the countryside surrounding Kobane, hundreds of residents stayed in their villages and homes. Many of them were elderly residents who could not escape due to the lightning speed of ISIS’ advances. ISIS fighters assaulted and killed many of them, while abducting others and taking them to nearby towns and cities such as Raqqa, Tal Abyad and al-Shuyoukh. Many of those taken were later killed in public squares, while the fate of some two hundred other civilians remains unknown, according to testimonies collected for this chapter. Because of Kobane’s significance to the Kurdish political movement as well as the anti-ISIS conflict, even being from Kobane was sufficient grounds for persecution at the hands of ISIS fighters.

One victim arbitrarily detained by ISIS remembered their experience:

When my brother Abdulkarim and I were coming from Cazire [Jazira] in our car, we were stopped by ISIS fighters at around 7 pm. As soon as they knew we were from Kobane, they asked us for our money, but we refused to give it to them. We told them that the money was ours, and that we had earned it through our own hard work.

They took us to their emir for him to give his verdict on us. When we arrived at his headquarters, they told us: “We’ll release you in an hour.” However, an hour or two passed, and they did not release us, and we did not see their emir. Then, somebody came to us, tied our hands, and put a piece of cloth over our eyes and then beat us badly.

Afterwards, they took us somewhere, but we didn’t know where. It was at night, they put us in a cellar and above us was a petrol station. They came to us every five minutes or so and beat us up. They used various methods of torture. They would put a knife to our necks to scare us and beat us with the butt of their rifles or with cables. They tortured us with electricity.[36]

Eventually, the two men were released. Others simply disappeared without a trace. The relative of one abductee, their father, kept trying to get information about him, but “his phone was off”:

After several attempts and repeated inquiries about him, they told us that the abductees were being held at silos in Tal Tamr [after] ISIS fighters, at one of ISIS’ checkpoints, abducted them all. [My father] was with his friends and a minibus driver. There wasn’t just one car on the road at the time [there]. [So] ISIS abducted some 80 people and took them all to Tal Abyad. After that, we didn’t hear anything about them.[37]

ISIS advances were accompanied by large-scale theft of civilian property as well as livestock, furniture, agricultural machinery, cars, crops and about anything else that ISIS fighters could lay their hands on. Service facilities and houses were destroyed and stripped down, with ISIS fighters taking anything of worth—power transformers, electrical grids, water diversion pumps from the Euphrates. Schools and other facilities were destroyed.

The ISIS offensive—characterised by use of car bombs, suicide bombings, and heavy shelling— and the fight to halt it, including through US-led Coalition airstrikes, caused major destruction in Kobane. According to the Autonomous Administration, more than 70% of Kobane was destroyed during the siege, including civilian homes and infrastructure,[38] while the remaining areas were also severely damaged.

In the countryside, ISIS converted schools into military centres for its fighters, which created protracted interruptions to local education and deprived thousands of children access to schools during the offensive and long afterwards. For others, the threat of kidnapping by ISIS prevented them from leaving Kobane to go to university. According to one interviewee, for example:

My daughter was a university student. My son-in-law and my son [stopped] their education because ISIS was kidnapping or killing students. My children were afraid to go to university because ISIS had previously detained 13 cars, and all the passengers were from Kobane.

Even until now, education is almost non-existent. In Kobane, there is a university run by the Autonomous Administration, however, it’s not officially recognised.[39]

The threat of kidnapping was very real: on 29 May 2014, ISIS kidnapped 153 Kurdish schoolboys between the ages of 13 and 14 years old in Manbij as they travelled back from Aleppo to Kobane.[40] The boys were beaten with hoses, forbidden from speaking Kurdish, and indoctrinated in ISIS’ ideology.[41] The boys were kept as ISIS hostages until September 2014, months after their kidnapping. During the subsequent ISIS offensive on Kobane, conflict monitors documented ISIS’ use of child soldiers to attack Kobane (although it was not immediately clear when those children had been forcibly recruited into ISIS’ ranks).[42]

Ideologically, ISIS’ attacks on Kurds were underpinned by fatwas, or religious edicts, issued by ISIS’ religious authorities. These justified targeting Kurds, who were said to be “atheists,” “disbelievers” or even “pigs,” with this messaging also distributed through audio and video transmissions. ISIS’ tactics of oppression, intimidation and murder were also intended to spread terror and subjugate populations; the group also considered its brutal application of violence a way of enticing new fighters, especially foreign fighters, to join ISIS on the promise of loot, plunder, and sexual conquest. Kurdish property, and at times Kurdish women, were considered “spoils of war” and thus could legitimately be captured. Kurdish “repentance” was considered unacceptable, in stark contrast to other areas such as Raqqa and Deir Ezzor, where ISIS considered their inhabitants to be Muslim, even if their religious interpretation had to be corrected through the application of Islamic Shari’a as interpreted by ISIS.

‘A return to a primitive kind of life’: Destruction in post-siege Kobane

Violent clashes continued between the YPG, YPJ, Peshmerga and FSA on the one hand and ISIS fighters on the other. By mid-November 2014, the YPG and YPJ controlled the eastern and southern fronts inside Kobane and carried out operations against ISIS outside the city. At this point, the YPG and YPJ announced offensive military operations to liberate Kobane, while ISIS was forced into a defensive position. As a result of this defeat, ISIS resorted to bombing residential neighbourhoods in a last-ditch attempt to regain lost ground, including through the use of suicide bombings and remotely detonated car bombs.

Over the course of November and December that year, the YPG and allied forces retook the city, fighting house by house, street by street, and then neighbourhood by neighbourhood. Finally, on 26 January 2015, Kobane was declared liberated.[43] It is estimated that as many as 3,710 ISIS fighters died, a number that included many ISIS commanders, although the exact number is difficult to ascertain because ISIS reportedly burned the bodies of its dead.[44] The end of the siege on Kobane represented a major turning-point in the anti-ISIS conflict, and Kobane became a key hub in the efforts to eliminate ISIS’ presence in Syria while crucially solidifying cooperation between YPG fighters and the US-led Coalition.

As Kurdish forces declared the city liberated, many of the refugees who had been displaced to Turkey returned.[45] For those who returned, the ordeals of displacement, poverty and hunger accelerated their desire to return home and restore their lives. However, months of fighting had turned homes, buildings, schools and hospitals to rubble and ash. Long after ISIS’ removal, Kobane still faced the threat of mines, booby traps and unexploded munitions, which were still killing civilians after the war had ended. In outlying rural areas, dozens of villages were partially destroyed, along with hospitals, irrigation networks, sanitation infrastructure and electricity networks. Several factors meanwhile created obstacles to returns, including the scarcity of raw materials and food, the lack of manpower and the difficulty of transport within Kobane, as well as the profound psychological impacts of war.

Many residents who had fled during the siege returned to find their homes destroyed; instead, they were forced to live in tents pitched among the rubble. Kobane had turned into a dystopian landscape. One woman described what she saw after the end of the fighting:

After ISIS’ attack, our suffering increased, and Kobane returned to a primitive kind of life. There was no electricity. Women washed clothes with their hands [and] cooked food on firewood. Water was scarce. We would take water out of the well with a bucket to get our drinking water.[46]

The lack of safety, the spread of decomposed bodies under rubble and the extinction of livestock caused by the war had turned Kobane into a ghost city. Because people who relied on agriculture and livestock had lost their primary sources of income, there was widespread unemployment. Infrastructure was destroyed, and most rural residents’ properties had been looted and robbed of crops and agricultural machinery.

One testimony described the economic destitution that Kobane residents faced:

One of my relatives lost approximately 130 sheep, which ISIS took as spoils. They took all the machinery, cars, and tractors. We lost all of it.

During [ISIS’] brutal attack, people could only save themselves and their children and run away. They left heavy machinery behind and just took their cars and fled. Until today, we still see some stolen machinery in Deir Ezzor, Raqqa and Manbij [after] ISIS sold its spoils [from Kobane] there. They took everything.

When we returned to Kobane, the only thing we found were the walls of the house still standing. It was not easy.[47]

Those economic impacts are still reverberating throughout the area until today. According to one resident of a village near Kobane:

Fear and anxiety continue to overwhelm us. Economically, there was a significant impact on us because […] we primarily depended on agriculture in the region. [But] for several years now, agricultural seasons have seen poor yields.

During the ISIS attack on Kobane, they seized our agricultural land, plundered and stole everything, including crops, harvesters and tractors, taking everything in the village. They took control of the lands on the basis that they belonged to them. They took everything.[48]

ISIS returns

With the return of residents to the city, clean-up efforts began with rubble clearance and temporary housing and tents provided to returnees. It was amid these efforts, in a supposedly post-conflict Kobane, that ISIS launched another attack on the city. In the early hours of the morning of 25 June 2015, ISIS fighters once again attacked in what would later be described as a 24-hour ‘killing rampage.’[49] A young woman, just 11 years’ old when the attack occurred, remembered that morning:

My father and uncle, who would later also be killed, went to the border gate to find out what was happening. My father came running towards us to tell us to hide inside the house. He was unarmed, and ISIS members were standing far away and shooting him.

After we entered the house, we heard the sound of shooting. My uncle told us the news that my father had been killed at the hands of [ISIS]. At that moment, my mother had just prepared milk for my nine-month-old brother. She left him in my arms and ran to my father. I stood at the door of the house and saw my mother trying to pull my father, but she couldn’t. She left him to come back later, but ISIS shot her [as well]. My uncle took me into the house, and I took my siblings into the room and locked the door on them. I went to my father and mother, who were still alive [lying] two meters apart. My mother held my hand, but she told me to go back to my siblings.[50]

It soon became apparent that ISIS fighters had managed to evade YPG forces (then busy on frontlines in Sarrin and Tal Abyad) through the village of Barkh Botan, where they killed 23 civilians, including women, children and the elderly.[51] The YPG later said that ‘a group of mercenaries consisting of 80 to 100 [fighters]’ entered Kobane ‘with the aim of committing a massacre of civilians’ after reaching the city in small groups reportedly disguised as FSA fighters.[52] The statement also alleged, citing anonymous local sources, that some ISIS fighters had also entered Kobane via Turkey.[53]

Once inside Kobane, ISIS fighters spread throughout the city’s neighbourhoods and positioned themselves on the rooves of tall buildings. One survivor recalled the havoc that ISIS snipers wreaked through the city:

I went downstairs to go to the bakery […] and after 50 metres, a bullet came from the direction I was walking toward. We realised that snipers were shooting at whoever they saw.

The second shot came immediately afterwards and hit my hand. I saw blood coming out [of my hand]. I was trying hard to reach one of the parked cars in front of the bakery [when] I realised that the shots were coming from the Boys Secondary School that sits on a hill higher-up […] about 150 metres from my house. It didn’t hit me directly because I was moving so quickly.[54]

Interviewees saw the killings as deliberate retaliation against Kurds for having broken the siege of Kobane a year earlier. Victims recalled how ISIS fighters killed anyone they encountered:

They set up a checkpoint, targeting anyone who passed them by firing shots at them. No one was spared from their evil. It was as if they were hunting birds, just enjoying the deaths of innocent civilians. They left no one alive. They killed men, women, children and the elderly. They killed everyone without exception.

At first, we didn’t know they were ISIS fighters because they were wearing Kurdish forces’ clothes. They even knocked on people’s doors and immediately killed anyone who opened up. Some of them had good Kurdish and they spoke in Kurdish while knocking on the doors so that people would open the door for them. Some ISIS fighters were using guns with silencer.[55]

ISIS occupied buildings and committed massacres at several sites throughout the city, targeting the Autonomous Administration building, roadways to Aleppo and Şêranê (Shiran), the Jumarek neighbourhood in northern Kobane, the city centre, and the nearby villages of Tarmīk Bījān and Barkh Botan.[56]

But ISIS fighters also infiltrated people’s homes. One man, who watched his wife tragically killed in front of him and their young children, described how ISIS fighters entered:

When I tried to get out of bed, they shot me from behind. There were two ISIS militants standing next to us. As I remember, I was trying to get to the door to get to the gun, even though they shot me. I didn’t lose consciousness.

I did later, though. They killed my wife and threw my children inside the house. My children were seven and four, and our youngest was just five or six months’ old. He was crawling to his mother’ s body to breastfeed from her chest. He thought she was asleep. It was 11 in the morning. He was in his mother’s lap and breastfeeding from her chest, but she was already dead.[57]

In its massacre in Kobane, ISIS deliberately targeted and executed civilians,[58] a form of revenge aimed at killing the largest possible number of civilians to avenge the group’s defeat during its earlier siege of Kobane. According to statements from the YPG and the Executive Council of the Autonomous Administration’s Kobane Canton, 233 civilians were killed in the massacre (including 210 in Kobane itself and another 23 in Barkh Botan village, in addition to 273 people who were injured).[59]

The aftermath

As the fighting ended in Kobane and surrounding areas, life gradually returned to the city. However, the humanitarian and psychological impacts of ISIS’ violence have been profound. In post-ISIS Kobane, victims, survivors and the families of those killed live with sadness and despair. One interviewee vividly described this feeling:

When we go to the cemetery on the night of Eid and light candles, we remember and feel pain as if it were the day of the massacre. We relive the horrific scenes that we cannot forget. As we grow, our painful memories grow with us. We can’t forget.

I can tell you my story. But I can’t tell it to a member of my family. My brother was a good friend of mine and I wish I’d died instead of him. He was two years older than me, but that was his fate.[60]

Another family’s life was completely upended by the conflict. Their home was destroyed, the store they owned was looted and partly demolished. A family member described feeling “broken”:

Nothing was left for us. Our crops and trees were burned during the battle for Kobane. My mother had a neurological disease. We all became mentally ill. My little sister fainted.

My mother doesn’t remember anything anymore. She always just repeats: “It’s gone, it’s gone…” She does not recognise any of her children. All her nerves were damaged, until she ended up just lying on her deathbed. She was in pain and did not tell the doctors. She passed away after three years of suffering. We cannot forget this trauma.

My family was in Turkey, then they left for Germany. Only me and my brother are still in Kobane. We managed to open our father’s shop again. I now have a disability in my hands and legs. Despite that, I have to work as a meter reader and bill collector for the electric company so that I can afford to support my children. Living conditions are very difficult nowadays.

From time to time, I see a doctor because of my injury. The medical costs make my life difficult. I always take medication because I have limited mobility in my hands and leg. My wife also receives constant treatment. I need to have an operation to remove a platinum plate, and after I contacted doctors in Damascus, they told me that would be an extremely expensive operation that could cost 10 million Syrian pounds [around €700].[61]

Much of people’s trauma—and especially their psychological symptoms—remains untreated to this day. A mother described how ISIS’ attack on their family home impacted the family and caused one of her sons to develop epilepsy:

My children were so afraid. Some of them peed themselves. My daughter looked out of the [spyhole in the door] and told me they killed my father. They killed my husband and cousin in front of me. My children were terrified, and then my son suddenly fainted.

Since then, he has developed epilepsy. This [disease] has stayed with him until now. He occasionally becomes completely unconscious. After [his epilepsy developed], I took him to see several neurologists and psychologists, but [they haven’t been able to help].[62]

These traumas live on in children who witnessed ISIS atrocities, impacting another generation of life in the city. Another Kobane resident described how their seven-year-old nephew developed a severe psychological condition “because he watched ISIS kill his father.”[63]

Battles continued after the liberation of Kobane city, and it would take months before ISIS was pushed out of the entire district. The group’s defeat at Kobane was a crucial step in the final defeat of ISIS some four years later, a major turning-point that would shape the contours of the anti-ISIS conflict that followed.

Kobane was a formative test for US (and US-led Coalition) engagements with Kurdish armed groups, many of which would later fall under the umbrella of the US-backed SDF. This Kurdish-led group, formed in late 2015, would go on to seize Manbij in mid-2016 and later advance on ISIS’ heartlands in Tabqa and Raqqa in 2017.

Footnotes

[1] Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics, ‘Syria Population Census, 2004’ (Ar.) (n.d.) <https://web.archive.org/web/20151208115353/http://www.cbssyr.sy/General%20census/census%202004/pop-man.pdf> accessed 17 August 2023.

[2] Hurriyet Daily News, ‘Explained: Kobane or Ayn al-Arab?’ (Istanbul, 28 October 2014) <https://www.hurriyetdailynews.com/explained-kobane-or-ayn-al-arab-73591> accessed 15 August 2023.

[3] Map Action, ‘Syria District Maps: Ain al-Arab’ (4 July 2016) <https://maps.mapaction.org/dataset/217-2791/resource/445fbacd-87c3-4ce8-9a99-98531eb22dfe> accessed 15 August 2023.

[4] The “Separatist Movement” (which called itself the “Supreme Arab Revolutionary Command of the Armed Forces”) was formed immediately after the collapse of the Egyptian-Syrian United Arab Republic. The census therefore took place during a period of successive coups and counter-coups that centred on issues related to the United Arab Republic and pan-Arabism. The Ba’ath Party seized power the following year.

[5] For example, the census and its resulting impacts also limited Kurds’ access to health, education, employment and property or land ownership.

Human Rights Watch (HRW), ‘Syria: The Silenced Kurds’ (October 1996) <https://www.hrw.org/reports/1996/Syria.htm> accessed 31 July 2023.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Interviews with Hasakeh Directorate of Civil Registry officials, April and May 2023.

[8] Ibid.

[9] France24, ‘Assad seeks to appease Kurds by granting citizenship’ (Paris, 7 April 2011) <https://www.france24.com/en/20110407-syria-granted-citizenship-kurds-assad-protests-unrest-emergency-rule> accessed 16 August 2023.

[10] Interviews with Hasakeh Directorate of Civil Registry officials, April and May 2023.

[11] Individual testimony #64, focus group session 3.

[12] Ibid.

[13] The Syria Report, ‘Explained: Laws Regulating Real Estate Ownership in Syria’s Border Areas’ (4 October 2022) <https://hlp.syria-report.com/hlp/explained-laws-regulating-real-estate-ownership-in-syrias-border-areas/> accessed 15 August 2023.

[14] Individual testimony #75, focus group session 4.

[15] HRW, ‘The Silenced Kurds’.

[16] Individual testimony #64, focus group session 3.

[17] Individual testimony #55, focus group session 3.

[18] Robert Lowe, ‘The Syrian Kurds: A People Discovered’ (Chatham House, January 2006) <https://www.chathamhouse.org/sites/default/files/public/Research/Middle%20East/bpsyriankurds.pdf> accessed 15 August 2023.

[19] Ibid.

[20] Carnegie Middle East Center, ‘The Kurdish National Council in Syria’ (Diwan, 15 February 2012) <https://carnegie-mec.org/diwan/48502> accessed 15 August 2023.

[21] YPG members later stated that the YPG was actually formed in the midst of the Qamishli Uprising in 2004, although it emerged out of the Kurdish political underground after the outbreak of the post-2011 uprising.

See: Danny Gold, ‘Meet the YPG, the Kurdish Militia That Doesn’t Want Help from Anyone’ Vice News (31 October 2012) <https://www.vice.com/en/article/yv5e75/meet-the-ypg> accessed 16 August 2023; Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), ‘Syria: Rojava Kurdistan’ (n.d.) <https://ucdp.uu.se/additionalinfo/13042/1> accessed 15 August 2023.

[22] Charles Lister, The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency (Oxford University Press, 2015), p.154.

[23] Harald Doornbos & Jenan Moussa, ‘The Civil War Within Syria’s Civil War’ (Foreign Policy, 28 August 2013) <https://foreignpolicy.com/2013/08/28/the-civil-war-within-syrias-civil-war/> accessed 15 August 2023.

[24] Ahmed Ali and others, ‘Iraq Situation Report: September 29, 2014’ (Institute for the Study of War, 29 September 2014) <> accessed 15 August 2023. https://www.iswresearch.org/2014/09/> accessed 15 August 2023.

[25] Ayla Albayrak and others, ‘Thousands of Syrian Kurds Flee Islamic State Fighters Into Turkey’ The Wall Street Journal (New York City, 9 September 2014) <https://www.wsj.com/articles/thousands-of-syrian-kurds-flee-islamic-state-fighters-into-turkey-1411151657> accessed 15 August 2023.

[26] United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), ‘9th Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’ A/HRC/28/69 (5 February 2015), Annex II, para.270.

[27] Ibid., para.279.

[28] Ibid., para.84.

[29] Ibid., para.67.

[30] Reuters, ‘Three suicide attacks hit Kurdish town on Syria-Turkey border’ (13 October 2014) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-bombing-idUSKCN0I20RI20141013> accessed 15 August 2023.

[31] BBC, ‘Islamic State “retreating” in key Syria town of Kobane’ (London, 16 October 2014) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-29629357> accessed 15 August 2023.

[32] Humeyra Pamuk and Raheem Salman, ‘Kurdish peshmerga forces enter Syria’s Kobani after further air strikes’ Reuters (1 November 2014) <https://www.reuters.com/article/uk-mideast-crisis-idUKKBN0IK15I20141101> accessed 15 August 2023.

[33] United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), ‘9th Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’ A/HRC/28/69 (5 February 2015), Annex II, para.279; Jenna McLaughlin, ‘Most US Airstrikes in Syria Target a City That’s Not a “Strategic Objective”’ Mother Jones (23 January 2015) <https://www.motherjones.com/politics/2015/01/airstrikes-syria-kobani-statistics-operation-inherent-resolve/> accessed 15 August 2023.

[34] Individual testimony #56.

[35] Individual testimony #55.

[36] Individual testimony #64.

[37] Individual testimony #68.

[38] Olivier Laurent, ’ Inside Kobani and the Kurdish War Against ISIS’ (TIME, 27 August 2015), https://time.com/4003737/kobani-isis-photos/ accessed 15 August 2023.

France24, ‘Years after IS, Syrian Kurds rebuild Kobane alone’ (Paris, 9 June 2018) <> accessed 15 August 2023.https://www.france24.com/en/20180609-years-after-syrian-kurds-rebuild-kobane-alone> accessed 15 August 2023.

[39] Individual testimony #63, focus group session 3.

[40] UNHRC, 9th report, Annex II para.102.

[41] Ibid., para.167.

[42] Ibid., para.70.

[43] BBC, ‘Syrian Kurds ‘drive Islamic State out of Kobane’ (London, 26 January 2015) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-30991612> accessed 15 August 2023.

[44] Jawad al-Hattab, ‘Kurds: 3,710 from ISIS killed in Kobane’ (Ar.) Al-Arabiya (30 January 2015) <https://www.alarabiya.net/amp/arab-and-world/iraq/2015/01/30/-%D8%A7%D9%84%D8%A3%D9%83%D8%B1%D8%A7%D8%AF-%D9%85%D9%82%D8%AA%D9%84-3710-%D9%85%D9%86-%D8%AF%D8%A7%D8%B9%D8%B4-%D9%81%D9%8A-%D9%83%D9%88%D8%A8%D8%A7%D9%86%D9%8A-> accessed 15 August 2023.

[45] Reuters, ‘Syrians slowly return to Kobani after Kurds win back border town’ (23 February 2015) <https://jp.reuters.com/article/mideast-crisis-syria-kobani-idINKBN0LR1DI20150223> accessed 15 August 2023.

[46] Individual testimony #55, focus group session 3.

[47] Individual testimony #36.

[48] Individual testimony #49.

[49] Al Jazeera English, ‘ISIL on 24-hour “killing rampage” in Syria’s Kobane’ (Qatar, 27 June 2015) <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2015/6/27/isil-on-24-hour-killing-rampage-in-syrias-kobane> accessed 17 August 2023.

[50] Individual testimony #5.

[51] HRW, ‘Syria: Deliberate Killing of Civilians by ISIS’ (3 July 2015) <https://www.hrw.org/news/2015/07/03/syria-deliberate-killing-civilians-isis> accessed 15 August 2023.

[52] AANES Canton of Kobane, ‘Executive council issues statement revealing circumstances of the Kobane massacre’ (Ar.) (13 December 2015) <https://cantonakobane.wordpress.com/2015/12/13/%d8%a7%d9%84%d9%85%d8%ac%d9%84%d8%b3-%d8%a7%d9%84%d8%aa%d9%86%d9%81%d9%8a%d8%b0%d9%8a-%d9%8a%d8%b5%d8%af%d8%b1-%d8%a8%d9%8a%d8%a7%d9%86-%d9%8a%d9%83%d8%b4%d9%81-%d9%81%d9%8a%d9%87-%d9%85%d9%84%d8%a7/> accessed 15 August 2023.

[53] Ibid.

[54] Individual testimony #1.

[55] Individual testimony #2.

[56] AANES Canton of Kobane.

[57] Individual testimony #62.

[58] HRW, ‘Deliberate Killing of Civilians by ISIS’.

[59] AANES Canton of Kobane.

[60] Individual testimony #47.

[61] Individual testimony #41.

[62] Individual testimony #57.

[63] Individual testimony #47.