Manbij’s location is highly strategic: it sits close to the Syrian-Turkish border, the M4 international highway, the Euphrates River and the Tishreen Dam, which produces up to 630 megawatts of electricity and irrigates surrounding agricultural land. Because of this, the city has always acted as a key determinant of the balance of power in northeast Syria—a role reprised during the Syrian civil war and the anti-ISIS conflict.

Manbij before the conflict

Located 80 kilometres from Aleppo and 30 kilometres west of the Euphrates, Manbij falls within Aleppo province. The city of Manbij and the 285 villages in its district were estimated to contain some 400,000 people in Syria’s 2004 census;[1] although no reliable statistics exist, today the area is estimated to host some 600,000 people, about half of whom are displaced from other parts of Syria.[2] Its population is primarily Arab, with Kurdish, Turkmen, Circassian and Chechen minorities; some of its inhabitants practice Naqshbandi Sufism.[3] Manbij is home to over 30 Arab clans and tribal culture plays a significant role in social relations, at times trumping the influence of political authorities.

Manbij is one of the largest cities in Syria and its history reaches back to the ancient dynasties that once spread across northeast Syria. The city’s name derives from the Hittite word Mabough, which has evolved several times throughout history, to Nambiji in Syriac and Nabijou in Aramaic. It was later called Maabij and Naabouj, which means “spring.” The present-day pronunciation stems from Classical Syriac.

After the end of the French Mandate in Syria in 1946, Manbij experienced a period of relative stability characterised by open political debate and discussion around democracy. This period ended in 1963, when the Ba’ath Party seized power and imposed a militarised one-party dictatorship throughout Syria. The Ba’athist regime in Damascus administered the city through the Ba’ath Party and its security apparatus, which imposed control over all aspects of public life. Party branches reached down to village level, while the mukhabarat threaded surveillance into every aspect of life. Even so, Manbij enjoyed a stable relationship vis-à-vis central authorities in Damascus, unlike other cities and regions of northeast Syria (on account of their differing ethnic, sectarian, or political compositions, as was the case in Kurdish-majority areas such as Kobane and Hasakeh).

Manbij is rural and agricultural, thanks to its bountiful water supplies and proximity to both the Euphrates and its tributary, the Sajur, which separates Manbij from the town of Jarabulus. Given the region’s climate and its suitability for farming, many residents raised sheep, cows, poultry and (rainfed and irrigated) crops such as wheat and barley, as well as tree crops such as olives and pistachios. The Syrian government would buy the harvest from farmers at the end of each season, at prices determined by the Agricultural Bank Directorate in Manbij city. A farmer talked about how he used to make a living from agriculture before the conflict:

The government used to strongly support agriculture. It would provide seeds and fertilizers, pay out in reasonable instalments, and get our produce to market. If there was a drought or poor rainfall, our payments would be postponed out of consideration for the farmers. The government served farmers well; the situation was incredibly good before the rise of [ISIS].[4]

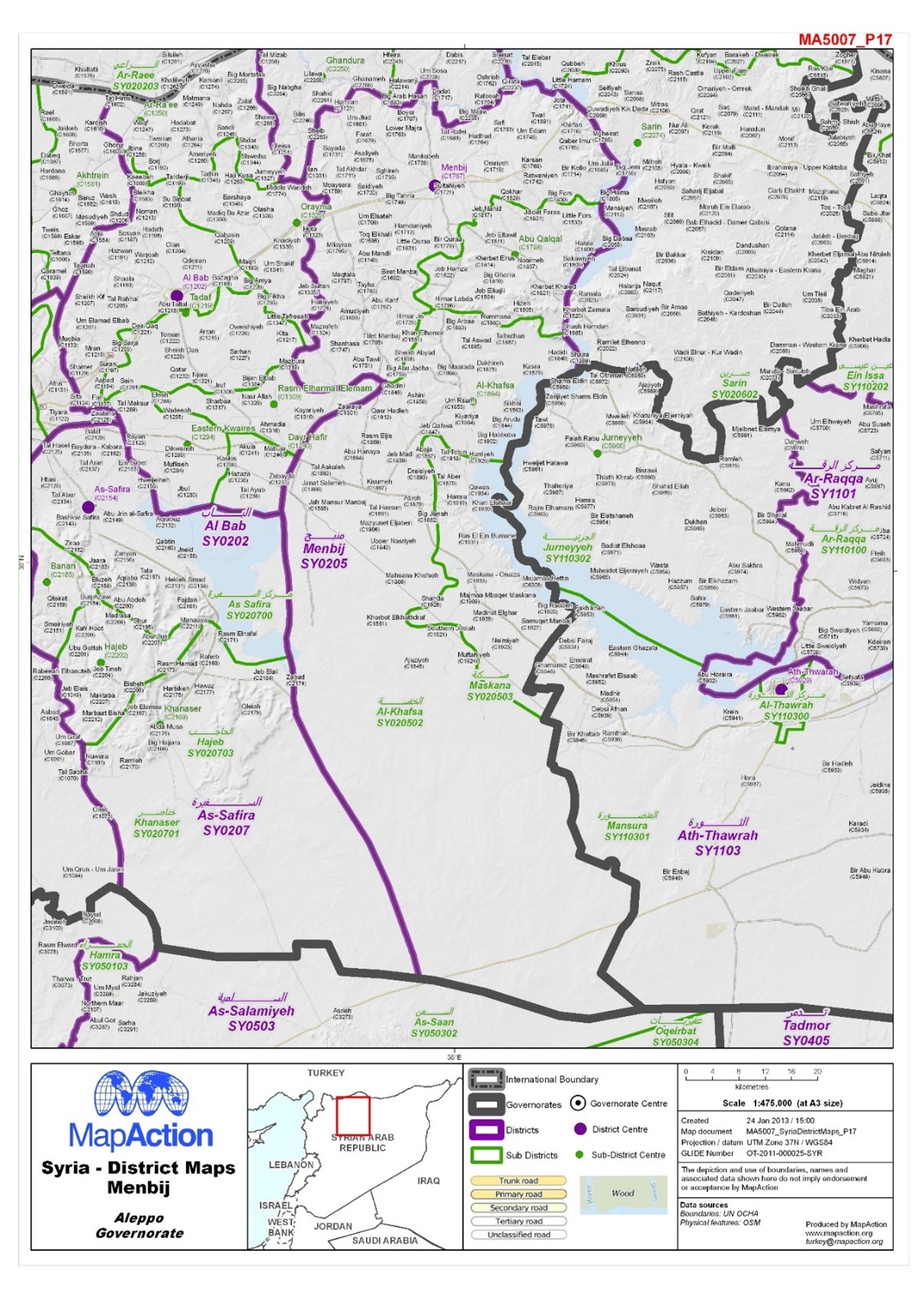

Figure 3: Manbij district in Aleppo province.[5]

A villager from Manbij district similarly remembered life in the region before the outbreak of unrest in 2011, describing the situation as “comfortable”:

Our life was good. Everyone had access to education, which was compulsory up until middle school. There was an educational renaissance, as we had both male and female students at universities. In our village alone, we had fifteen university graduates.

The economic situation was comfortable. Prices were cheap and stable. For example, I was a university student, studying English literature. I used to work one day a week, and one day’s work would be enough to cover my expenses for the entire week. The economy was good, and so was our standard of living.[6]

Women worked freely alongside men, both in the agriculture sector and other professions. Women could study, pursue further education, and, if they had the means, travel unrestricted for education, work, or medical treatment. Women in Manbij were free to dress as they liked, with no restrictions except those imposed by social customs, norms, and traditions. When discussing gender relations before the conflict, a woman from Manbij said:

We were safe; we could walk around safely. We would go shopping and wear whatever we liked. When we got sick, we wouldn’t be afraid or worried, because medical services were available. When a woman was about to give birth, we wouldn’t worry if her husband wasn’t with her, because we could take her to the hospital. As women, we would do what we liked, we were responsible for everything in the home when our husbands were not around. We would take care of shopping or anything that the home or the children needed.[7]

Forced marriage practices had almost disappeared from Manbij and new laws were passed to alleviate the injustices that women had suffered for generations. Reforms were made to an article that previously exonerated a man for “honour killings” when murdering one’s wife, daughter or sister if caught in the act of adultery,[8] before that law was then abolished altogether. There were also changes in social norms that improved the lot of women, allowing them to join the police and armed forces. Organisations were formed to defend women’s rights such as the General Women’s Union.

Nevertheless, women were still cut out of inheritances from both their father and mother; in most cases, their estates were liquidated under law, and, to make matters worse, women had to complete difficult and expensive procedures to assert their rights.

Not everyone in Manbij benefitted from the pre-conflict situation, however. During the rule of Hafez al-Assad, and then his son, Bashar, public life was heavily securitised, and the intelligence services played a role in repressing anti-government political activism. The Ba’ath Party, through its Manbij branch, managed education, and teachers in both the city and countryside could only work if they were active, card-carrying members of the party. The party imposed its ideology from primary school onwards, where younger pupils were called the Ba’ath’s tala’a (vanguards); high school students joined the shabiba, or Ba’athist Youth. Students sitting admission exams for universities could gain preference if they first underwent a month-long Ba’athist training programme. As in the rest of Syria, Manbij city had plenty of schools and teaching staff while, the countryside lacked such services.

Manbij was also part of the “Arab Belt” project, when the Syrian government granted fertile lands belonging to Kurds along the Syrian-Turkish border to Arab settlers. In 1974, thousands of Arab families were moved from Manbij to 43 settlements extending from Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain to the village of Ain Dewar within the Derik/al-Malikiyah administrative region. In 1999, the government carried out another displacement operation, moving residents of upstream villages due to be submerged by the Tishreen Dam to the city of Maskanah.

Furthermore, the large merchant class in Manbij, which had long flourished due to its proximity to Syria’s man trading hub, Aleppo, lost ground under the Assad regime. Land reform benefitted a rural constituency but took power away from the Sunni Hadhrani merchant class and members of the wealthy, powerful Albu Sultan tribe, who increasingly gravitated toward the anti-Ba’athist, conservative messages of the Muslim Brotherhood after the 1970s.[9] These groups would form the core of Manbij’s Sunni Muslims who joined the Muslim Brotherhood’s post-1979 insurgency, which was brutally repressed in Hama in 1982. And like Hama, Manbij too was attacked with tanks during the regime’s crackdown, terrifying the city’s residents for years after.

In the years leading up to the next major bout of anti-regime unrest in 2011, the Manbij region was neglected and saw little economic development. Under the reforms carried out by Bashar al-Assad in the mid-2000s, Hadhrani merchants and traders from Manbij lost out to their counterparts in Aleppo and Damascus.[10] Having retained their ties to the Muslim Brotherhood, they would become leaders in the anti-Assad opposition once the Syrian uprising broke out in March 2011.

The conflict in Manbij

Stability in Manbij did not last. Early on in 2011, the region joined anti-government protests, staging its first demonstrations within a month from the outbreak of protests in Dera’a. Soon, the city saw protests almost every night as well as the creation of a Revolutionary Council, which was dominated by Hadhraniand Albu Sultan liberals and Islamists with close connections to the Muslim Brotherhood.[11]

In June and July 2012, as Qatar furnished Brotherhood-affiliated groups such as Liwa’ al-Tawheed with Libyan-sourced weapons delivered through Turkish territory, towns across Idlib and Aleppo provinces fell to the opposition.[12] Manbij, where the Revolutionary Council had created an armed wing in early 2012, came under FSA control in July that year. Assad’s forces withdrew with hardly a shot fired.[13]

On the one hand, the takeover of Manbij by Syria’s armed opposition ushered in a period of experimentation with participatory democracy and saw the establishment of a local council. Nearly a dozen independent newspapers emerged around the same time.[14] Due to its mixed population and social structures, Manbij acted as a more open and liberal society than other Sunni-majority cities nearby (such as al-Bab), and women were regularly seen in the street with their hair uncovered.[15]

Over time, the region became a site of chaotic, factional infighting between armed opposition groups.[16] More than 70 armed groups emerged after the government withdrawal (and local research conducted for this report even found more than 90 armed factions were present in the area.) Those who lacked access to weapons and connections to external benefactors or Brotherhood-linked Hadhrani networks conducted freelance raids on police stations to obtain weapons; kidnappings and looting were also commonplace.[17] Increasing competition between Saudi Arabia and Qatar meanwhile, led the latter to increase its backing for the Salafi-jihadi armed group Ahrar al-Sham, which announced its presence in Manbij in early 2013.[18] By April, Ahrar al-Sham-led forces were in control of the city and Liwa’ al-Tawheed warned the Revolutionary Council not to resist the city’s new rulers.[19]

The arrival of ISIS

Allied with Ahrar al-Sham in the takeover of Manbij was Jabhat al-Nusra, then undergoing its schism with ISIS. At the time, Manbij saw both anti-ISIS protests and religious outreach by the group through da’wa (outreach)meetings.[20] According to interviews conducted for this report, ISIS’ Jordanian emir Abu al-Harith al-Urduni founded the first ISIS cell in the area in 2013 with just a few dozen fighters in Manbij at the time. Some were local emirs or members of ISIS’ security and intelligence apparatus, but the majority were foreigners who had entered Syria across the Turkish border—some alone, others with their families—from various Arab and European countries as well as Uzbekistan and Chechnya.[21]

It was a turbulent time for Manbij, and many residents were unhappy about the direction the city was taking:

Before [ISIS] came, we were ruled by the FSA. We were surrounded by chaos and gangs, and we did not feel safe. Everybody worked in their respective trade, but education came to a halt. All the schools became military bases, or else the FSA destroyed them. They destroyed and looted schools and government buildings.

Before ISIS, I used to travel to Jordan. I was a builder. After the regime left, militias and gangs controlled everything. So, I stayed at home. I could not travel any more. We weren’t safe anymore in our homes and with our families.[22]

At first, ISIS did not significantly interfere with the lives of Manbij’s residents. Foreign fighters occupied the cultural centre downtown and patrolled public markets, carrying their weapons.[23] By July 2013, however, Ahrar al-Sham and ISIS had made a power play, halting all grain shipments from Maskanah and Raqqa to Manbij, causing the price of bread to skyrocket.[24] ISIS organised protests against the Revolutionary Council; Ahrar al-Sham stayed neutral.[25]

By January 2014, the Revolutionary Council had lost popular support and when ISIS swept across swathes of northeast Syria, in an operation led by Abu Omar al-Shishani, ISIS’ future “minister of war,” the group took control of Manbij with relative ease.[26] Ahrar al-Sham, which by then had fallen out with ISIS and, together with Nusra and the FSA, was engaged in a violent struggle against the group, was expelled from the city. Around 100 ISIS fighters, many of them British, took up residence in Manbij, earning it the nickname “Little London.”[27]

Fighting in the area continued for a while, with the Syrian government accused of using internationally prohibited cluster munitions against ISIS and other rebel forces in the area.[28] However, it would be several years before ISIS was forced to relinquish control over the city.

‘Their eyes spread everywhere’: ISIS’s stifling social programme in Manbij

After seizing Manbij, ISIS launched a widespread campaign of arrests targeting members of FSA factions that had controlled Manbij as well as civilians who supported them. While former members of Manbij’s Revolutionary Council migrated to Turkey or areas remaining under armed opposition control,[29] those who did not get out in time were captured and either taken to detention centres or executed in public spaces. Their bodies were often left hanging for days. Others were taken to nearby al-Bab, where ISIS had an intelligence headquarters.

ISIS policies had a stifling social impact in Manbij. Chaos was replaced with profound fear. A Manbij resident described how ISIS forced family members or to spy on one another:

[ISIS] tried to entice young men and children to get involved and join its ranks. It used material temptations like money, women, and the promise of houriyat [heavenly virgins] in paradise. Under their rule, there was no security or trust between people and their neighbours. Even within the same family, there were ISIS spies. Their eyes spread everywhere. People couldn’t even speak in front of their children. You couldn’t smoke in front of them, because ISIS fighters would come to the streets, give the young children sweets or money, and ask if any of their parents or carers smoked. If the child said yes, the person would be arrested. People became scared of each other.[30]

Another stated that society became “fragmented” by fear:

“Everyone became afraid of each other. You started being afraid of your neighbours’ son because he could get you killed.”[31]

As in other areas under its control, ISIS imposed a rigid social programme based on its regressive interpretation of the Quran and Shari’a. A woman from Manbij described its impacts:

ISIS banned funeral wakes. [They] put a lot of pressure on people getting married, even obliging the bride to wear black all over. You stopped seeing weddings at all. The group imposed clothing restrictions on both women and men. It forced women to wear black clothes covering their entire bodies—their faces, eyes and hands—and banned them from wearing coloured clothes.

It also forced men to wear a short gown that ended above the heels, and to grow their beards and trim their moustaches. Anyone who violated ISIS dress codes was stripped of their ID card, imprisoned, whipped, forced to take a course in Shari’a, and abused and humiliated.[32]

There was no room for other religions; in downtown Manbij, ISIS smashed the tombstones of the cemetery because they considered them to be idolatrous.[33] Meanwhile, ISIS facilitated the quarrying and looting of antiquities in Manbij and the rich archaeological sites in the outlying countryside.[34] The group was also involved in drug sales. At the same time, it halted those economic activities that did not serve its own interests and passed laws limiting economic activity among the population. It closed individual businesses and imposed strangulating restrictions on various professions. This caused unemployment to soar and sowed poverty among all social classes. The same woman from Manbij recounted how:

On top of all the teachers leaving their jobs, ISIS closed government offices [so] all the civil servants lost their jobs. Students were out of school, too. Many lawyers were forced to leave their careers, and so were gynaecologists. ISIS banned their profession, saying it violate[d] Islamic law and could even be considered blasphemy. The whole society suffered.[35]

The group made special efforts to recruit children, capitalising on the fact that they could be easily manipulated and indoctrinated into total loyalty to the organisation. This was achieved through religious education, by exploiting poverty and gaining leverage over the population through cash handouts, and by recruiting children into spying networks. A Manbij resident said:

ISIS closed the schools and used all its platforms and media outlets to attract young people and drag them into its hateful terrorist organisation, inculcating them with extremist and takfiri ideas. We no longer had education. The schools were closed.

Education also stopped for university students, as no-one dared to travel to Aleppo or Damascus to pursue their studies, for fear of [ISIS] because it banned traveling to “infidel countries.”[36]

‘They put my brother’s head on the block’: Public executions

Nevertheless, ISIS initially kept some distance between itself and the city’s residents, relying on local tribal structures when it came to governance. Maintaining popular support in Manbij was vital to the group; the region served as its main gateway to the outside world, via the Turkish border. With ISIS engaged in drawn-out battles elsewhere in 2014, Manbij was spared the worst of the group’s abuse.

This changed following ISIS’ defeats in Kobane and Hasakeh. As ISIS started to lose territory, it increasingly ruled Manbij with an iron fist. It took revenge on residents in areas under its control, launching widespread arrest campaigns. The group instilled fear among the people by carrying out executions in public squares on various charges, such as blasphemy or for having alleged or real connections to the Syrian government, the FSA, or the PKK. ISIS also targeted other religious and ethnic minorities, including Christians and Manbij’s Sufi population, seeing their expulsion as its legitimate duty in building a “cleansed” Islamic state.

On 4 April 2015, ISIS executed four people from the village of Rummana, near Manbij. The incident occurred after a woman from the village complained to the group that her husband had married another woman, who was Alawi. The woman accused him of having dealings with infidels and Nusayris, a derogatory, sectarian term for members of the Alawi sect. ISIS fighters responded by executing the man on the al-Dilla Roundabout in Manbij’s al-Hazawnah district. Later, one of the man’s sons—who was affiliated with ISIS—was killed. The woman then accused a group of young men of the murder. ISIS arrested and beheaded them publicly with a sword in front of the village mosque following Friday prayers while their families watched.[37]

A man from another family described their experience with ISIS’ brutality:

We went to an ISIS office to collect our car after they had seized it. But the fighter [in the office] kept delaying my father and then told him: “Sit near the car and wait.”

My father got angry and argued with him, but the fighter insisted that he sit next to the car. Finally, he stood next to it. A few minutes later, the car exploded. I was about ten metres away from my father, but I was sitting on the ground, while my father was standing. A large piece of shrapnel hit him in the stomach. I watched him lean against a wall, say the shahada [Islamic statement of faith] and die.

I was hit by shrapnel in my shoulder and under my arm. A group of civilians were also wounded in the explosion, including a woman whose clothes were torn off. The explosion was caused by ISIS and not by an air strike as ISIS claimed.[38]

After his father’s death, the man hoped that his uncles, who had been arrested, would be released. In January 2016, however, they found out that ISIS had executed all three on charges of supporting the FSA and having dealings with Kurdish groups.[39]

Many public executions were carried out with extreme cruelty—by gunfire or beheading with swords. ISIS even publicly crucified victims and left them hanging on crosses for days while preventing families from burying them, to spread terror among opponents. Executions were usually conducted in public squares or in front of mosques, especially before or after Friday prayers, to gather the biggest possible crowd.

A witness whose brother was decapitated described the harrowing experience:

After detaining and torturing him, on a Friday morning before prayers, ISIS came to the village. They were heavily armed and had twelve military vehicles and a group of masked mercenaries. All the village residents were gathered in front of the mosque in the square, and the man with the sword appeared. He was terrifying.

He first showed off his strength and swung the sword around, to spread fear in the crowd. Then they put my brother’s head on the block, and with one blow, they separated his head from his body, in full view of the villagers.

They didn’t hand over the corpse after they slaughtered him. Instead, they carried the corpses, crucified them, and hung them for three days on the roundabouts of Manbij. Only after three days were the corpses handed over to us.[40]

Another eyewitness described the trauma of witnessing a beheading in front of their village mosque:

They brought the man, who was over 50 years’ old, and said that he had been practicing witchcraft, and they would punish him as required by Shari’a. They beheaded him with a sword.

I tried to look away, but in the end, I saw his head separated from his body. I was deeply shocked by that awful sight. That night I couldn’t eat or sleep, especially as my son […] had been detained by ISIS.

At the beginning of the execution, I hid at the back of the crowd so I wouldn’t see them killing this man. The sight of him being killed next to the mosque was terrible for everyone in the village, young and old. It left a dreadful psychological scar on me and everyone in the village.

‘They were waiting for her to turn 10’: Violations against women and girls in Manbij

ISIS fighters adopted several methods to either obtain wives or exploit women sexually, justifying their practices on various religious pretexts. The group set up “marriage offices” to arrange two types of marriage. Through the first type, so-called consensual marriages, ISIS fighters would marry a non-ISIS or “common” woman, often seeking out particularly beautiful women and exploiting the dire economic conditions of poorer families. The second form of marriage was explicitly forced: the group would accuse a family member of blasphemy or apostasy and force the family into accepting a marriage in exchange for the charges being dropped.

A witness talked about ISIS policies against women during its control in Manbij:

There was an ignorant man, a criminal, aged about 70. He was an ISIS judge. He took two girls from the village and married them by force at the Tishreen Dam housing complex. The group had a horrible custom: when an ISIS member had a wife or wives, he could recommend that they be passed to an emir or to other ISIS fighters in the event of his death. Then, when he died, his comrades would take the women and divide them amongst themselves, without the women having any say, and without respecting the ‘idda.[41] All this was laid out in orders handed down by ISIS‘ leadership.[42]

Another practice, known as “sexual jihad,” saw women “married” to ISIS fighters to provide sex and boost their morale. This was barely disguised sexual slavery and usually involved some form of coercion.

The strict yet idiosyncratic implementation of religious policies did not just affect women: men too could face severe consequences if accused of immoral or impure behaviour. At least one man in Manbij was stoned to death for allegedly committing adultery. The mother of the stoning victim talked about how her son was killed on trumped-up charges:

An ISIS patrol came and arrested my son, Alaa. When I visited their detention centre, they told me he was charged with adultery. They claimed they had done a virginity test and discovered he had committed adultery with a mute woman, who was now four months pregnant.

I told them: “My son just got married, why would he be involved with another woman?”

But they weren’t convinced by this. I spent a month visiting them, while my son sat in prison with no idea about the charges he was facing.

Then, on 10 October 2015, an [ISIS] patrol came and delivered his body to the house. They told us: “We carried out the punishment for adultery and stoned him to death.”[43]

However, women certainly suffered some of the worst abuses. Like in other areas under ISIS control, in Manbij the group brought hundreds of Yazidi women and girls from the Sinjar area of Iraq and sold them at “slave-girl markets.” ISIS treated these women as a sexual commodity to be bought, sold, or disposed of as the group and individual fighters saw fit. Most of the group’s ideas and laws about women saw them as awrah, as unclean or shameful beings. One Manbij resident detailed how ISIS traded in women:

I saw that some ISIS fighters brought girls from outside the country, aged just nine or 10 years’ old. They said the girls’ fathers were fighting the group, so they had taken them as hostages. There was one nine-year-old girl. They were waiting for her to turn 10, so one of them could marry her. There was an office for marrying minors. They wouldn’t accept older girls, only those aged 12 to 17 years’ old.[44]

Most buyers were ISIS fighters and their relatives, who had arrived with the group from other Syrian cities or from abroad. Research conducted for this report found no cases of Manbij locals buying these women as slaves; however, on dozens of occasions, Manbij residents bought Yazidi girls and women to rescue them, mirroring a practice documented elsewhere in Syria and Iraq.[45] This was carried out in coordination with the Kurdish-led SDF, YPG and YPJ, which liaised with Manbij residents and sent them money so they could “buy” Yazidis and bring them to the banks of the Euphrates, from where they could escape to SDF-held Kobane.[46] In retaliation, ISIS arrested and killed several Arab residents accused of helping Yazidis escape or smuggling Kurds or Kurdish-owned property to SDF-controlled areas east of the Euphrates.

Violations targeting ethnic minorities

ISIS also systematically targeted Manbij’s Kurds. As it was locked in a protracted battle with the Kurdish-led SDF, which was backed by the US-led Coalition, ISIS viewed all Kurds in Manbij with extreme suspicion and treated them with absolute contempt. Kidnappings, killings, and other abuses were used to specifically target the Kurdish population in rural Manbij; this also included Kurds who had married into Arab clans to avoid the wrath of the group. Kurds in rural areas avoided going to the city for fear of being arrested. Anyone caught trying to leave would be charged with attempting to escape and join the SDF or PKK to fight ISIS.

The father of a Kurdish victim described how his son was killed on accusations that he worked with Kurdish forces:

My son’s charge was that he had the name “Dilberin” tattooed on his hand. An ISIS member told me: “This is the name that killed your son.” They caught him at the border and brought him to Manbij. They promised me that after 15 days I could see him. But they executed him.

They told me: “We killed your son because he was affiliated with the PKK.” I know for sure that he was not affiliated with them. He simply had the name Dilberin tattooed on his hand. It’s a Kurdish name. This is what killed him. My son had been married just 40 days earlier. He got married, and then he died.[47]

Another Kurdish victim described a relative’s horrific encounter with ISIS:

My sister’s husband […] was working in Beirut but came to Manbij to see his family. While he was there, he was captured by [ISIS]. Fighters came to his family home to arrest his brother, [but] they also arrested [my brother-in-law] and another brother. Of course, as Kurds, they were both accused of belonging to the PKK.

They were held for three months. Several other people were detained with them. After three months, they were all released except for [my brother-in-law] and his two brothers. Three months later, I was in Aleppo, and I heard that ISIS had executed [him] and hung his body up at the Seven Seas Roundabout in Manbij. I went to the roundabout and there it was, the body of my brother-in-law, hanging [there]. It was a horrific sight.

I kept monitoring the place. Three days later, ISIS members came in a car and took the body away, so I followed them to find out where they would put it. I was riding a motorbike and was able to follow them without being noticed. When they reached the Matahin Roundabout, they went around it twice, trying to cover their tracks. After that, they went to the eastern cemetery in Manbij city and laid the body in front of it. They dug a [mass grave] in the pavement, measuring about 100 metres’ long and two and a half metres’ deep. They put the corpses on top of each other and covered them with soil, with the help of two other ISIS members, who used to sit there in a tent and wait for vehicles to arrive with bodies to bury.[48]

Almost all young Kurds in the area fled. The remaining Kurds in Manbij were trapped, as ISIS increasingly seized Kurdish-owned houses and properties. ISIS held public auctions at large warehouses in Manbij city to sell seized Kurdish real estate, furniture, cars and other items. Elderly residents and others who stayed began sleeping on farms or in the open air to avoid night-time raids and arrest campaigns by ISIS, only sneaking back to their homes just before dawn.

‘They killed the men, and if the women screamed, they killed them too’: The al-Buwayr massacre

After fending off the siege of Kobane and making gains in Hasakeh, the SDF and US-led Coalition prepared for their offensive on Manbij.[49] They recaptured the Tishreen Dam in late 2015 and then the town of Sarrin in early 2016. At the end of May, the offensive got underway, and progress was initially swift: by 10 June, the SDF had encircled Manbij city.[50] French special forces were also reportedly heavily involved in fighting on the ground.[51]

Nevertheless, it would take more than two months of protracted fighting before ISIS was finally expelled from Manbij. ISIS threw manpower and resources into defending the city, which it considered a vital strategic corridor and communications hub linking ISIS power centres across Syria and Iraq. Although the SDF had gained a foothold in the city by the end of June, ISIS launched the first of two major counter-offensives to break the siege the following month.[52] These were repelled, and the SDF advanced further. On 10 July, the ISIS emir of Manbij, Abu Khalid al-Tunisi, was killed in the fighting.[53]

Over the rest of the month, ISIS lost further ground. It attempted another counter-offensive to break the siege to the west of Manbij in late July. This was when the people of the village of al-Buwayr woke up to an ISIS attack.

ISIS fighters infiltrated the village, raided houses and started shooting randomly at men, women, and children. They killed the men first, then several children and women. One eyewitness, a child at the time, recounted how:

[ISIS] members killed two displaced people who were living in the school. Three [ISIS] fighters killed my father, my mother, and my paternal uncles. They killed the men, and if the women screamed, they killed them too.

Another survivor, who was blinded by an explosion, remembered the immediate aftermath of the massacre:

I heard a loud noise and immediately lost consciousness. I don’t know what happened. I stayed unconscious for about three hours and when I came to, I heard people’s voices. The paramedics had come. Someone approached me, but because of the severity of the explosion, he didn’t even recognise me. It was my cousin. He told people, “Come and lift this person, he’s still alive!”

They carried me to the ambulance and took me and lots of other people to Manbij. When we arrived, they said I was dead, people didn’t believe I was alive.

One of my brothers came and asked about me, and they told him: “He’s dead.” Then I sat up and vomited blood.

They said: “Dead people don’t vomit. He must be alive. But he’ll die if he doesn’t get treated.” So, they took me to Qamishli because there weren’t enough doctors in Manbij. I was wounded in the eye.

I lost my sight after the operation. They stopped the bleeding, but they had to remove both of my eyes.[54]

A young boy was left quadriplegic and unable to speak or move.[55] ISIS terrorised another man, setting him alight several times, an experience that left him with serious mental issues, including memory loss.[56]

ISIS’ attack on al-Buwayr left around 30 people dead and dozens more injured,[57] and represented yet another example of the kind of extreme violence the group meted out across northeast Syria as its power began to wane.

‘We were hit by friendly fire’: Civilian casualties during Manbij’s liberation

During the final days of the battle for Manbij, ISIS members bunkered down in their security headquarters in central Manbij and gradually withdrew to the al-Sarb neighbourhood on the northern outskirts of the city.[58] By 12 August, the SDF had full control of Manbij.

The civilian toll during the fighting had been high. ISIS killed civilians who attempted to escape and repeatedly used car bombs. The last remaining ISIS fighters, according to the SDF, used civilians as human shields.[59] They also turned civilian homes and properties into military installations, or even disguised civilian homes as ISIS bases, to divert airstrikes away from actual ISIS infrastructure.

One eyewitness, whose house ended up on a frontline between ISIS and SDF fighters, described the devastating consequences this had for his family:

During the battle for liberation, four ISIS members turned up near my house. They were fighting with the liberating forces. Then three of them withdrew and one stayed. He was remarkably close to the house. After about half an hour, the shooting stopped, and I went out to see what was happening. I said: “Thank God, the fighting has ended, and everything is okay.”

That night, my brother and brother-in-law came, and the house filled up with family, with around 18 people there. When my brother and brother-in-law were about to leave, we were saying goodbye at the door when suddenly two missiles from a plane hit the house. They killed my daughter Fawzia, who was 14, and my granddaughter Naima, who was one-and-a-half years’ old.

We ran away carrying their bodies, but the aircraft fired at us again, killing my daughter Abir, who was 13, and my granddaughter Nadia, who was three. My wife, son and daughter went in a different direction that night. When we reached my brother’s house, we couldn’t find them. But when the sun came up in the morning, I saw all of their bodies […] lying on the ground after they had been hit. The Coalition warplanes had also bombed my house and destroyed it.

The bombing and destruction of my house and the killing of my family were all because of the four ISIS militants who’d started fighting the liberating forces near my house. They opened fire on the liberating forces from the east and west [sides] of my house, so the [SDF] and the Coalition thought that there were [ISIS] fighters permanently stationed in my house. They bombed it with the intention of wiping them out. But the victims were my family and my home. No one in my family […] was ever part of [ISIS].[60]

This incident was not a one-off. In late July, airstrikes allegedly carried out by the US-led Coalition in Tokhar, close to Manbij, killed entire families, including young children, thinking that they were fleeing ISIS fighters.[61] Incidents like this led anti-ISIS activists from the Raqqa is Being Slaughtered Silently campaign group to accuse the US-led Coalition of deploying a ‘scorched earth policy’ and dealing with Manbij civilians ‘as if they were terrorists or ISIS supporters.’[62] The US military, following an internal investigation, said 24 civilians had ‘intermixed with the fighters’ and that there was no evidence of negligence or wrongdoing. An on-the-ground New York Times investigation found more than 120 civilians were killed in attacks in which there was no evidence that ISIS fighters had been near any of the targets.[63]

By mid-August 2016, the opposition-affiliated Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR) documented the killing of at least 444 civilians, including 106 children, during the battle to liberate Manbij. Among them, 203 were killed in airstrikes on Manbij and the surroundings, while others died in gunfights, shelling and attempts to cross minefields planted by ISIS. The SDF lost more than 300 fighters during their campaign to liberate the city, while ISIS lost more than 1,019 of its fighters.[64]

The aftermath

The fall of Manbij was the biggest loss for ISIS since the liberation of Kobane in 2015. In the immediate aftermath of the defeat, many of the remaining ISIS fighters withdrew to Jarablus on the Syrian-Turkish border. Turkish tanks then crossed into Syria to drive ISIS out of the border town, and the FSA entered the region as part of the Turkish-led “Euphrates Shield” operation.[65] Shortly after ISIS’ defeat, however, clashes broke out between Turkish-backed armed groups and the SDF.[66] Eventually, a Russian-mediated deal saw the SDF turn over villages to government forces, to appease concerns from Turkey and its affiliated forces.[67]

Residents of Manbij, an Arab-majority city, soon expressed uneasiness about the possibility of being ruled by Kurdish-led authorities. The establishment of the SDF-aligned Manbij Military Council, a multi-ethnic local governance structure meant to acknowledge Manbij’s demographics, allowed for a slow return of displaced people to their homes. Even though Manbij had not suffered the kind of devastation seen in Kobane, many displaced residents found it difficult to return. Operations were launched to clear rubble in the city, but as with other areas recently liberated from ISIS, mines and unexploded ordnance among the debris killed and injured hundreds more after the group’s withdrawal.[68] The Manbij Military Council meanwhile, had limited resources and lacked much-needed specialists in most administrative and civilian sectors, while there was limited international support to meet the basic needs of the population through early recovery, livelihood and healthcare assistance. And yet the needs were immense: interviews with dozens of victims in Manbij revealed that close to none had received any mental health support at all since the end of the conflict.

By 2018, according to some accounts, Manbij was on a path to recovery. One visitor described it as a “boomtown” to which businessmen from Aleppo had flocked to profit from trade with the SDF-held areas.[69] Such reports, however, masked the economic insecurity experienced by ordinary families. One woman, widowed during the conflict, said:

My son is 13 years’ old, which is a critical and dangerous age. But he goes to work to earn us a living. Is that normal? Sometimes [I] borrow money from my neighbours and grocers until my son comes back with money, just so that we have enough bread to survive. Is that justice? I’m not the only one in this situation, there are many like me.[70]

According to Manbij’s residents, there has been little progress in delivering justice and accountability to the many victims of ISIS in the area. For some, this should be economic, taking the form of reparations or compensation for material losses suffered during the conflict, including battle-related loss or destruction of property and confiscation by ISIS.

One demand from many in Manbij is for local authorities or the international community to conduct trials of ISIS members currently held in detention by the Autonomous Administration and SDF. A woman, whose husband was executed and crucified by ISIS, summed up her demands:

No agency provided us with anything. We sometimes hear that organisations are helping people, but no one has helped us. My appeal to the international community, to international justice agencies and to honourable people around the world is that they hold jailed ISIS members accountable, help children affected by the violations, support the families of victims, and try to redress the damage they have suffered because of [ISIS’] violations and its terrorist and criminal practices.[71]

Even when people were still trying to live with their traumas in the immediate aftermath of ISIS rule, the group demonstrated that it could still be a threat. On 16 October 2016, four ISIS suicide bombers infiltrated the village of al-Mashi and blew themselves up among a group of residents, killing eleven. Taking place just a month after al-Mashi had been liberated from ISIS, it was clear that ISIS cells remained a threat in the region.

Many of the group’s victims interviewed for this report feared that the group will be able to reconstitute itself and return. Manbij residents were clearly afraid to speak about or criticise the group or anything relating to it. They selected interview venues carefully, and spoke quickly to complete interviews as soon as possible, especially in rural areas.

Post-ISIS Manbij also remained caught in larger geopolitical tensions. Observers say that the divide between Turkey and the SDF-affiliated Manbij Military Council replicated similar fault-lines that plagued the city after the 1960s: with wealthy elites aligned with the Turkey-backed opposition squaring off with poorer members of Arab tribes aligned with the SDF.[72] Meanwhile, Turkish President Erdogan has repeatedly threatened to attack Manbij.[73] After US forces withdrew from Manbij in 2019, the YPG followed suit. In a telling reversal of fates for Manbij, Syrian government forces, expelled from the area in 2012, returned to the city accompanied by Russian armed forces.[74] By the summer of 2022, renewed talk of a Turkish invasion of Manbij led to increasing alignment between the pro-Assad forces and the SDF in the city.[75]

Footnotes

[1] Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics, ‘Syria Population Census, 2004’ (Ar.) (n.d.) <https://web.archive.org/web/20151208115353/http://www.cbssyr.sy/General%20census/census%202004/pop-man.pdf> accessed 17 August 2023.

[2] Interviews with Autonomous Administration officials, April and May 2023.

[3] Kheder Khaddour and Kevin Mazur, ‘The Struggle for Syria’s Regions’ (2013) MERIP Middle East Report 269 (Winter 2013) <https://merip.org/2014/01/the-struggle-for-syrias-regions> accessed 17 August 2023.

[4] Individual testimony #84, focus group session 2.

[5] Map Action, ‘Syria District Maps: Menbij’ (4 July 2016) <https://maps.mapaction.org/dataset/217-2790/resource/11cb9a20-63d1-448f-9a4e-21ec63379781> accessed 17 August 2023.

[6] Individual testimony #84, focus group session 2.

[7] Individual testimony #11, focus group session 3.

[8] Aman Bezreh, ‘A murder in Syria reignites the debate about so-called “honour killings”’ (Open Democracy, 13 July 2021) <https://www.opendemocracy.net/en/north-africa-west-asia/a-murder-in-syria-reignites-the-debate-about-so-called-honour-killings/> accessed 17 August 2023.

[9] Anand Gopal and Jeremy Hodge, Social Networks, Class, and the Syrian Proxy War (April 2021) New America, p.37, <https://d1y8sb8igg2f8e.cloudfront.net/documents/Social_Networks_Class_and_the_Syrian_Proxy_War.pdf> accessed 17 August 2023.

[10] Ibid.

[11] Ibid, p.38.

[12] Ibid., p.32.

[13] Ibid., p.38.

[14] Ibid., p.39.

[15] In nearby al-Bab, by comparison, armed opposition factions oversaw an overtly religious regime in which a woman wearing trousers was considered a transgression. See: Khaddour and Mazur, ‘The Struggle for Syria’s Regions’.

[16] Gopal and Hodge, p.39.

[17] Ibid., pp.42-44.

[18] Yasser Munif, ‘Participatory Democracy and Micropolitics in Manbij: An Unthinkable Revolution’ (The Century Foundation, 21 February 2017) < https://tcf.org/content/report/participatory-democracy-micropolitics-manbij/> accessed 22 August 2023.

[19] Gopal and Hodge, p.49.

[20] Aymenn Jawad al-Tamimi, ‘The Islamic State of Iraq and ash-Sham Expands Into Rural Northern Syria’ (Syria Comment, 18 July 2013) <https://www.joshualandis.com/blog/the-islamic-state-of-iraq-and-ash-sham-expands-into-rural-northern-syria/> accessed 17 August 2023.

[21] Information collected from interviews in Manbij, April and May 2023.

[22] Individual testimony #73.

[23] Gopal and Hodge, p.47.

[24] Ibid., p.49.

[25] Ibid.

[26] Ibid, p.49.

[27] Information collected from interviews in Manbij, April and May 2023.

[28] Human Rights Watch (HRW), ‘Syria: Evidence of Islamic State Cluster Munition Use’ (1 September 2014) <https://www.hrw.org/news/2014/09/01/syria-evidence-islamic-state-cluster-munition-use> accessed 17 August 2023.

[29] Gopal & Hodge, p. 49.

[30] Individual testimony #63.

[31] Individual testimony #72.

[32] Individual testimony #76.

[33] Patrick Cockburn, ‘In the small city of Manbij in Syria, we could see US and Turkish troops shooting at each other if tensions continue’ The Independent (London, 2 March 2018) <https://www.independent.co.uk/voices/syria-us-turkey-troops-fighting-manbij-kurdish-assad-civil-war-a8236201.html> accessed 17 August 2023.

[34] Adnan Almohamad, ‘The destruction and looting of cultural heritage sites by ISIS in Syria: The case of Manbij and its countryside’ (2016) International Journal of Cultural Property 28(2).

[35] Individual testimony #76.

[36] Individual testimony #72.

[37] Individual testimonies #17 and #22.

[38] Individual testimony #65.

[39] Ibid.

[40] Individual testimony #17

[41] Three three-month period a woman should wait before re-marrying after being widowed, as stipulated by Shari’a.

[42] Individual testimony #75.

[43] Individual testimony #77.

[44] Individual testimony #69.

[45] See: Kristen Chick, ‘With Mosul under siege, an unlikely chance to save ISIS-enslaved Yazidis?’ Christian Science Monitor (3 December 2016) <https://www.csmonitor.com/World/Middle-East/2016/1203/With-Mosul-under-siege-an-unlikely-chance-to-save-ISIS-enslaved-Yazidis> accessed 17 August 2023.

[46] Information collected from interviews with community members and local officials, April and May 2023.

[47] Individual testimony #74.

[48] Individual testimony #62.

[49] The operation was later named after Faisal Abu Layla, a key military leader in the liberation of Kobane, who was killed early in the fight to free Manbij.

See: Rudaw, ‘Hero of Kobane dies from ISIS sniper wound’ (5 June 2016) <https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/050620162> accessed 17 August 2023.

[50] Reuters, ‘U.S.-backed forces cut off all routes into IS-held Manbij: Syrian Observatory’ (10 June 2016) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-manbij-idUSKCN0YW0T1> accessed 17 August 2023.

[51] Vincent Nouzille, Les Tueurs de la République (Fayard, 2015).

[52] Reuters, ‘U.S.-backed militias face second Islamic State counter attack – official, monitor’ (4 July 2016) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-manbij-idUSKCN0ZK0SI> accessed 17 August 2023.

[53] ARA News, ‘ISIS Emir killed under SDF fire north Syria’ (10 July 2016) <https://web.archive.org/web/20160713063334/http://aranews.net/2016/07/isis-emir-killed-sdf-fire-north-syria/> accessed 17 August 2023.

[54] Individual testimony #11.

[55] Individual testimony #32.

[56] Individual testimony #41.

[57] This number was reached through testimonies collected in and around Manbij between April and May 2023. The Syrian Observatory for Human Rights conflict monitor initially reported that 24 civilians were killed.

See: SOHR, ‘IS executes 24 civilians 10km away from Menbej city’ (29 July 2016) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/48877/> accessed 17 August 2023.

[58] Interviews with Manbij residents, April and May 2023.

[59] Suleiman al-Khalidi and Lisa Barrington ‘U.S.-backed forces wrest control of Syria’s Manbij from Islamic State’ Reuters (12 August 2016) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-islamic-state-idUSKCN10N178> accessed 17 August 2023.

[60] Individual testimony #72.

[61] Max Bearak, ‘An airstrike in Syria killed entire families instead of Isis fighters’ The Independent (London, 22 July 2016) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/an-airstrike-in-syria-killed-entire-families-instead-of-isis-fighters-a7149771.html> accessed 17 August 2023.

[62] Lizzie Dearden, ‘War against Isis: US-led coalition accused of killing civilians using “scorched earth policy” in Syria’ The Independent (London, 5 August 2016) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/war-against-isis-usled-coalition-accused-of-killing-civilians-using-scorched-earth-policy-in-syria-a7174736.html> accessed 17 August 2023.

[63] Azmat Khan, ‘Hidden Pentagon records reveal patterns of failure in deadly airstrikes’ The New York Times (New York City, 18 December 2021) <https://www.nytimes.com/interactive/2021/12/18/us/airstrikes-pentagon-records-civilian-deaths.html> accessed 17 August 2023.

[64] SOHR, ‘The third US citizen fighter is killed in Manbij area and casualty number rises to about 1800 civilians and fighters’ (17 August 2016) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/49446/> accessed 17 August 2023.

[65] Lizzie Dearden, ‘Syria war: Turkish tanks cross border in huge operation to drive Isis out of key stronghold’ The Independent (London, 24 August 2016) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/europe/syria-isis-latest-news-turkey-tanks-offensive-attack-syrian-civil-war-jihadist-us-jarablus-north-a7206826.html> accessed 17 August 2023.

[66] Samuel Osborne, ‘Turkey threatens more Syria strikes if Kurdish forces do not retreat’ The Independent (London, 29 August 2016) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/turkey-in-syria-latest-news-strikes-syrian-civil-war-isis-attack-offensive-kurds-a7215241.html> accessed 17 August 2023.

[67] Lizzie Dearden, ‘Isis defeat in northern Syria opens deadly new phase in civil war as rebel groups turn on each other’ The Independent (London, 3 March 2017) https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/isis-northern-syria-defeat-civil-war-new-phase-rebels-bashar-al-assad-regime-sdf-turkey-us-russia-iran-a7610231.html> accessed 17 August 2023.

[68] HRW, ‘Syria: Improvised Mines Kill, Injure Hundreds in Manbij’ (26 October 2016) <https://www.hrw.org/news/2016/10/26/syria-improvised-mines-kill-injure-hundreds-manbij> accessed 17 August 2023.

[69] Cockburn, ’ In the small city of Manbij in Syria.’

[70] Individual testimony #53.

[71] Individual testimony #78.

[72] Gopal and Hodge, p.50.

[73] Al Jazeera English, ‘Erdogan threatens to extend Afrin operation to Manbij’ (Qatar, 24 January 2018) <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2018/1/24/erdogan-threatens-to-extend-afrin-operation-to-manbij> accessed 17 August 2023.

[74] Arab News, ‘Syrian and Russian troops sweep into Manbij as US withdraws’ (15 April 2019) <https://www.arabnews.com/node/1569256/middle-east> accessed 17 August 2023.

[75] Reuters, ‘Erdogan says Turkey to rid Syria’s Tal Rifaat, Manbij of terrorists’ (1 June 2022) <https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/erdogan-says-turkey-rid-syrias-tal-rifaat-manbij-terrorists-2022-06-01/>; Khaled al-Khateb, ‘Syrian Kurds, Arabs join forces to defend Manbij ahead of Turkish military operation’ Al-Monitor (24 June 2022) <https://www.al-monitor.com/originals/2022/06/syrian-kurds-arabs-join-forces-defend-manbij-ahead-turkish-military-operation> ; The Independent, ‘US-backed Syrian Kurds to turn to Damascus if Turkey attacks’ (London, 7 June 2022) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/americas/us-politics/recep-tayyip-erdogan-ap-turkey-ankara-damascus-b2095634.html> accessed 17 August 2023.