Raqqa province lies in the centre of northeast Syria and spans both sides of the Euphrates River, which passes through the heart of the provincial capital of the same name.

The city would take on profound symbolic importance during the years of ISIS rule over northeast Syria as well as the military campaign to defeat the group. When Abu-Bakr al-Baghdadi declared ISIS’ “caliphate” in June 2014, he proclaimed Raqqa as its capital. Some have suggested that this was an attempt to portray ISIS as the second coming of the Abbasid Caliphate, with Baghdadi as caliph Harun al-Rashid, the most powerful of the Abbasid rulers. However, the decision may also have been informed by Raqqa’s central location within ISIS-controlled territory and its easy access to the Syrian-Iraqi border.

Raqqa before the conflict

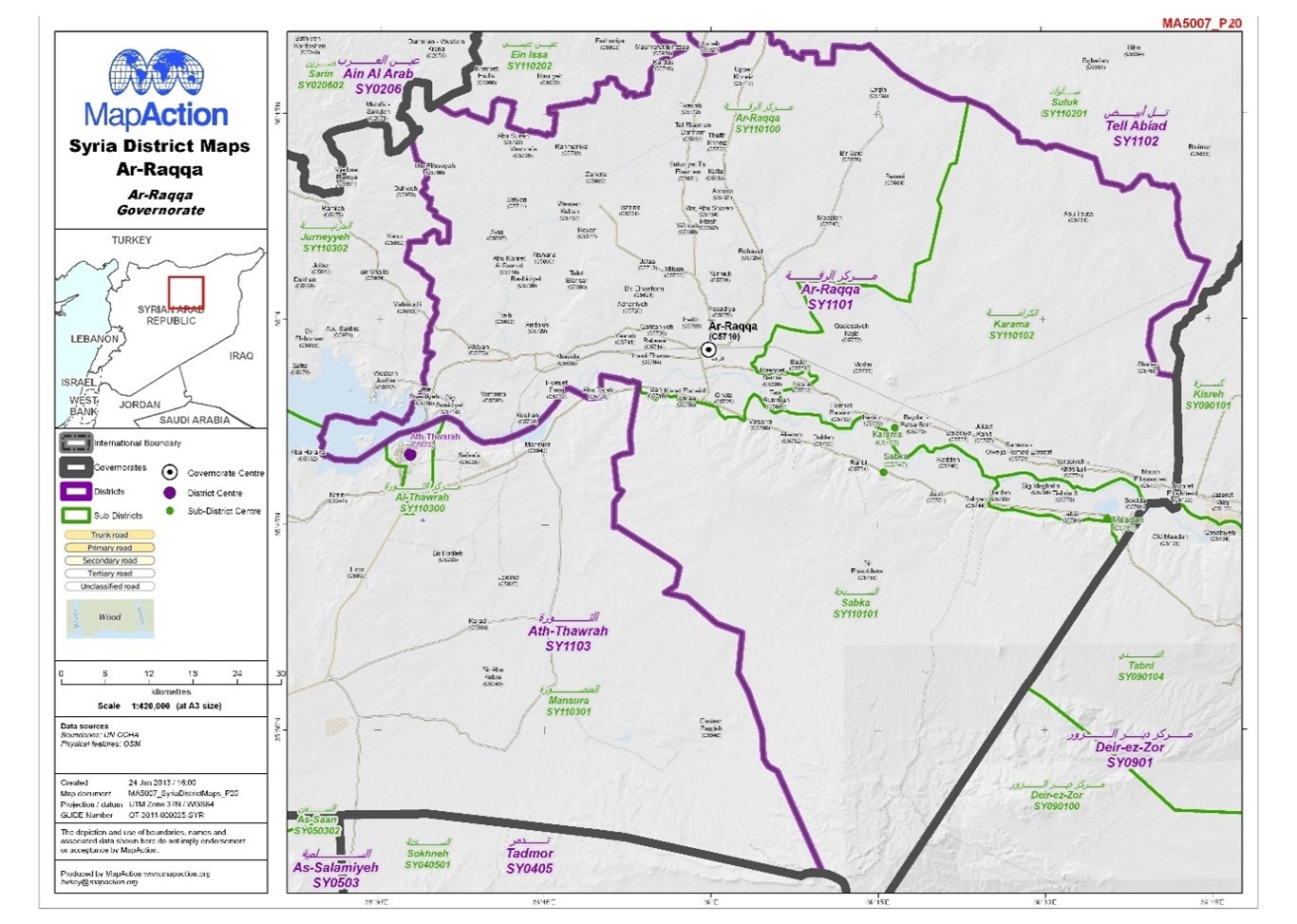

Raqqa city is located around 90 kilometres south of the Syrian-Turkish border, nearly 200 kilometres east of Aleppo and 140 kilometres northwest of Deir Ezzor. The province is divided into seven main districts. The main city other than Raqqa is Tal Abyad, a name meaning “white hill,” which lies north of Raqqa city at a point close to the Turkish border and the town of Akçakale. Other key towns include Ain Issa, Maadan, Tabqa and al-Mansoura.

Raqqa has a long, storied history. Its name derives from the Arabic word for “flakes,” raqa’iq, referring to the layers of clay sedimented by the seasonal flooding of the Euphrates. Floods are followed by a cracking of the soil surface as the water evaporates, leaving behind flakes or fine particles of substrate.

Raqqa is one of the ancient cities of the Arab world, with traces of influences from ancient Semitic city-states such as Mari as well as the Greeks, Romans, Persians, Assyrians, Abbasids, Selchuks and Ottomans. During the Abbasid era, between 750 and 1258 CE, there were two cities called Raqqa—the first, known as “white Raqqa” after the colour of its bricks; while the second, “brown Raqqa” (because of its brown baked bricks), was developed by Abbasid caliph Abu Jaafar al-Mansour, starting from the year 772 CE. Built in the shape of a horseshoe, like Baghdad, it served as the summer capital of the Abbasid state. Monuments of the various civilisations are scattered across the city and its environs. They include the archaeological site of Tuttul (or Tal al-Bay’a) built by the Mari civilisation, the Old Mosque in central Raqqa that was built under the caliph Mansour, and the Archaeological Museum constructed by the Ottomans as a government headquarters in 1861.

It was the Ottomans who established the modern city of Raqqa, bringing urban order to an otherwise sparsely populated area. The Ottomans intended to shore up a defensive void on their borders that extended from the Levant to the edge of the Syrian desert. Nevertheless, the city failed to provide much in the way of defence from Bedouin attacks from the desert. There were echoes of this pattern when, centuries later, ISIS swept across the desert to take control of the city.

Modern Raqqa absorbed waves of immigration, from Aleppo and its hinterland as well as other inland parts of Syria, especially the al-Sukhnah area of the Homs desert. Groups of Armenians sought refuge in Raqqa when fleeing massacres and genocide in the crumbling Ottoman Empire in 1915. Kurds also immigrated to the city, primarily from Iraq; indeed, there were so many Kurdish families that the first entries in the city’s civil registry bore the adjective “Kurdish” alongside several families labelled as “Circassian.” While the Kurds lived mostly to the north of Raqqa city, most of its modern residents were Sunni Arabs who primarily lived near the banks of the Euphrates. Some Armenian Christians remained in Raqqa city, although many of them had already left the region for Aleppo by the late 20th century. By 2004, the year of the last official Syrian census, Raqqa city and the surrounding area were home to a total population of just over 506,300 people.[1]

As in nearby Deir Ezzor, clans play an important role in the area. Even so, Raqqa’s clans did not represent power centres capable of contesting central authorities’ economic and social structures. The Ottomans had long maintained relationships with clans and tribes in various areas of Raqqa province, but the layout of the modern city that they constructed also fragmented clan ties. This meant that, unlike Aleppo or Deir Ezzor, there were no significant tensions between different clans or communities in the decades leading up to the Syrian conflict.

Figure 5. Raqqa district in Raqqa governorate.[2]

Located on a periphery between desert and agricultural regions, Raqqa never took on a truly urban character. The city grew rapidly during the construction of the Tabqa Dam, which drew migrants from Syria’s coastal regions who occupied administrative roles and worked in education. Furthermore, the “pioneering project” that brought water from the Euphrates through a system of canals to irrigate large swathes of agricultural land required large numbers of experienced farm labourers. This sparked an influx of migrants from rural Aleppo and Deir Ezzor, while Armenians and Kurds revived industrial production of agricultural machinery such as tractors and harvesters. During this influx, many of Raqqa’s districts were named after their incoming residents’ origins: Hay al-Bab for migrants from al-Bab; Hay Abna Tadef for migrants from Tadef (close to al-Bab); and Hay al-Akrad for Kurds, many of whom moved from Kobane and Afrin to Raqqa in search of work. Each new influx added to the region’s unique social fabric.

While the government could have harnessed the electricity of the nearby Tabqa Dam and surrounding agricultural land to develop Raqqa into an industrial and commercial powerhouse to rival Aleppo, neglect by central authorities left it lagging behind other cities. Viewed as a remote, barren place whose residents were uneducated and behind the times, Raqqa’s residents were referred to as shawaya, a derogatory name indicating backwardness and a lack of culture. As in other parts of Syria, Kurds living in the north of the province faced systemic marginalisation and political repression. And yet, even Raqqa’s Arab communities were looked down upon by the authorities.

By the 1960s, despite several leftist and communist movements active in the province, the Ba’ath Party emerged bent on eliminating its ideological rivals. As in other peripheral parts of Syria, power was centralised and exerted through the regime’s notorious security apparatus. Security agencies had extensive involvement in society. Security passes were required for registration or sale of agricultural land or to start new shops, restaurants or car dealerships. A semi-clandestine class of informants, known as “report-writers,” emerged. Political life was reduced to the Ba’ath Party and the National Progressive Front, a coalition of regime-tolerated leftist parties dominated by the Ba’athists. The authorities relied on compliant tribal elders to fill parliament seats and represent the region at public events. Most senior government jobs were reserved for members of specific tribes or tribal factions.

Underground movements did emerge in response to the Ba’ath Party’s dominance, but never seriously threatened the regional balance of power. Raqqa’s Arab nationalists were closer to the Iraqi branch of the Ba’ath Party, a connection fostered by family ties on either side of the border. It also helped that Iraqi television reached Raqqa decades before Syrian state television did. Some of these tensions were accentuated by the Iran-Iraq conflict in the 1980s, in which the Syrian Ba’ath supported Iran’s revolutionary Shi’a regime against its rival Ba’athist regime in Iraq.

New religious currents grew, mostly with Sufi tendencies. Following the Muslim Brotherhood’s uprising starting in the late 1970s, Raqqa experienced a further crackdown on cultural activities and public gatherings. The decline in freedoms resulted in greater displays of religious affiliations, especially the expansion of Shi’a shrines across the country. In Raqqa, a Sufi shrine for Owais al-Qarni, who had fallen in battle there, was developed and completed in 2003.[3]

Others responded to the lack of economic opportunities by migrating within Syria or outside the country (often to the Gulf, Lebanon or Jordan). Initially, this led to a brain drain. However, over time, it created a further backlash. Around the time of the US-led invasion of Iraq in 2003, people from both rural and urban areas of Raqqa returned from Saudi Arabia, steeped in the religious ideas of Sunni Wahhabismand the Hanbali school of Islamic jurisprudence. These were compatible with the conservative culture of the Raqqa countryside. Residents of rural Aleppo and Deir Ezzor moved to Raqqa, where they set up religious institutes inspired by similar Wahhabi teachings. The regime then facilitated the flow of Islamist and jihadist fighters to Iraq to fuel the insurgency against the US invasion and occupation. Over time, this deepened religious and clan cleavages in Raqqa’s society.

Despite the comparatively lower living standards in Raqqa and its perception in Damascus as a provider of natural resources and agricultural produce, services such as education and public hospitals remained free and most of Raqqa’s residents were able to get by. Unemployment was relatively low, as most of the population either worked in farming and manufacturing or as day labourers in various sectors, earning enough to make a living in the period prior to the war. Indeed, most interviewees reflected positively on pre-conflict times. A woman from Raqqa said:

My family and I had a reasonably good quality of life. My father worked as a [security] guard, […] one of my brothers was also working, and my other siblings were at school or university. All our material needs were covered, and we had access to education and job opportunities. Women generally had freedom in all aspects of life, including the ability to work and study.[4]

Raqqa’s residents enjoyed access to a good number of primary and secondary schools, a teacher-training institute, and vocational colleges for professions such as nursing, agriculture, and manufacturing. The population was overwhelmingly young due to a high birth rate and the practice of polygamy by some families, but also because of improvements in primary healthcare, including vaccination campaigns backed by the WHO against tuberculosis, measles, smallpox, polio and other infectious diseases. Women also had a large degree of freedom in education and work; at least one interviewee pointed out that women from Raqqa also sat in parliament.[5] Another woman from Raqqa described the sentiment that prevailed in Raqqa around the time:

Before [ISIS], women had complete freedom, including the right to education [and] to travel freely. They weren’t even obliged to show their identity cards. Women were free in all spheres, even if there were some limits since this is a tribal society.

Politically, we didn’t have freedom of speech. There was one party imposing its rule by force. [But] education was very good. It was mandatory up to the sixth grade—you couldn’t pull your kids out before that. And it was free. We weren’t afraid for our kids.[6]

This was a trade-off familiar to Syrians across the country whereby state-provided public services were expected to compensate for an absence of political freedoms and, to a lesser extent, individual social and economic rights.

All of that changed with the outbreak of the uprising and ensuing conflict after 2011. As one man put it:

People got on with their lives, even if things weren’t always easy. We had everything we needed. When [ISIS] came, 90% of that was lost.[7]

The conflict in Raqqa

Raqqa was spared fighting in the earlier stages of the Syrian conflict. The city was seen as too loyal to Assad, who relied on tribes to quell dissent.[8] There were few, if any, anti-government demonstrations in Raqqa during the early days of the uprising. Possibly in acknowledgement of this, towards the end of 2011, while armed opposition groups were spreading in other parts of the country, President Bashar al-Assad chose to celebrate Eid al-Adha in Raqqa’s al-Nour Mosque.[9] After the ceremony, Assad met with notables and tribesmen, many of whom had reportedly been paid up to $100,000 each for their continued support of the regime.[10]

But the tactics that had worked for the regime in previous decades began to falter. With the conflict intensifying across Syria, fighting eventually reached Raqqa province. While it was the last governorate to witness anti-government demonstrations, Raqqa was paradoxically the first to fall entirely outside the government’s control. First, Tal Abyad fell to the armed opposition in September 2012.[11] Armed opposition groups, including the Raqqa Liberation Front (Jabhat Tahrir al-Raqqa), a coalition of 80 mostly Islamist groups, and al-Qaida affiliate Jabhat al-Nusra, increasingly seized large swathes of territory in the province and soon cut off the highway between Raqqa and Deir Ezzor. [12]

In February 2013, armed groups were joined by Ahrar al-Sham for the offensive on Tabqa. Ahrar al-Sham organised a sub-group, Liwa Umanaa al-Raqqa, made up of fighters from Raqqa, to legitimise the offensive. In early March 2013, Ahrar al-Sham and Nusra entered Raqqa in an operation named the “Raid of the Almighty” with support from an eclectic coalition of Salafi, Brotherhood and FSA brigades.[13] The city fell within hours. Regime forces pulled out, handing the city’s eastern entrance to Nusra before withdrawing to the 17th Division military base on the outskirts of the city.[14]

After the capture of Raqqa, it was not long before infighting started. Ahrar al-Sham, which had planned the attack, took over captured government buildings but, according to local activists, they were neither prepared nor interested in governing and instead transferred captured funds to the group’s main base of operations in Idlib and Hama.[15] Others, however, stressed the role that Ahrar al-Sham’s proxy, Liwa al-Umanaa al-Raqqa, played in introducing Shari’a law in the city while at the same time providing public services—including a public bus network[16]

The opposition’s SNC, backed by Qatar as well as Saudi Arabia, sought to use Raqqa as a laboratory for the uprising and supported a local council formed around Raqqa-based lawyer Abdullah Khalil.[17] A supporter of the Syrian uprising from its early days and well-respected across the city, Khalil was a moderating force to Ahrar al-Sham and Nusra.

For Raqqa’s residents, however, the presence of numerous armed groups created a sense of lawlessness and chaos, worsened by the fact that the Syrian military, whose forces remained besieged in the 17th Division base, subjected the city to aerial bombing raids.

The arrival of ISIS

A month after the opposition took control of the city, the alliance between ISIS and Nusra fell apart.[18] ISIS fighters had made their first public appearance in al-Mansoura district, around 35 kilometres southwest of Raqqa city. By then, Raqqa residents recounted that Baghdadi had informed key ISIS figures that he planned to cut ties with Nusra and al-Qaida.[19]

Under the leadership of Abu Ali al-Shara’i, a key figure in ISIS at the time, the group began threading sleeper cells into local communities and recruiting new members through da’wa, or Islamic outreach, in the areas of Sabkha, Karama, Sulukh, Tabqa and some neighbourhoods of Raqqa city.[20] Newly recruited members were expected to inform the communities in which they operated—providing information on the identity and whereabouts of community leaders and their sources of income, as well as religious families. Sleeper cell operatives also collected compromising details on city residents: information about criminal backgrounds, sexual orientations, or illicit romances would be used as ammunition later.[21]

In the following months, Nusra’s governor in Raqqa, Abu Sa’ad al-Hadrami (originally Mohammed Saeed al-Abdullah), affirmed his continued support for Nusra. His deputy, Abu Luqman, meanwhile, took control of remaining ISIS fighters and Nusra defectors to ISIS.[22] Those who remained loyal to Nusra left Raqqa city and redeployed to the Tabqa Dam and nearby Jabaar citadel; Ahrar al-Sham moved its forces to Tal Abyad.[23]

As ISIS took control of Raqqa, it set up an Islamic court system with Shara’i as its chief judge. The group also stepped up its efforts to recruit foreign fighters through a social media campaign led by British ISIS fighter Abu Rania and Iman Mohammad Sheikha, a woman from al-Mayadeen near Deir Ezzor.[24]

ISIS then dealt with any remaining challengers. The group drove a 500-kilo car bomb into the headquarters of Ahfad al-Rasoul, the last remaining armed group in Raqqa[25]— reportedly the group‘s first suicide bombing targeting another armed group. Former Nusra commander Hadrami was then kidnapped and killed in September.[26] Local council leader Abdullah Khalil had likely befallen the same fate that May, although his body was never found, his murder was never acknowledged.[27] Muhannad Habayebna, a civil rights activist and journalist, spoke out against ISIS during a community meeting; five days later, he too was found executed.[28] By then, anti-ISIS protests had already largely dissipated after ISIS publicly executed three citizens at the city’s Clock Square on charges of “spying for the regime.”[29] With the stick came the carrot. When clan elders pledged allegiance to ISIS in November 2013—as they had done to Assad before, reportedly in exchange for payment—ISIS firmed up its control over Raqqa.[30]

In early 2014, as part of the emerging conflict-within-a-conflict between opposition groups and ISIS, Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham and the remnants of Raqqa’s FSA made a last-ditch attempt to recover the city. While they ousted ISIS from Raqqa on 6 January, ISIS returned a week later.[31] It would be three long years before ISIS would be forced to give up control of the city again.

‘Their heads were hung on the iron bars’: Executions of 17th division troops

Like in other areas it brought under its control, such as Manbij, ISIS took power brutally while promising to restore order and provide security for the population following the “chaos” of opposition rule. Indeed, there are some indications that, in the initial months that ISIS had full control over Raqqa, deaths in the city fell rapidly.[32] However, there may have been multiple causes for this, including the fact that there were fewer regime airstrikes during this period (especially compared to earlier periods when the city was under Ahrar al-Sham and Nusra control).

By pushing out all other opposition groups, ISIS prevented infighting and restored a sense of order. Now set up in its chosen capital, there was also an incentive to invest in Raqqa. ISIS established ministries and government offices in the city, often staffed by foreigners who paid generously in foreign currency. Recovered ISIS files revealed that the group had mandated its forces within Syria and Iraq to seize strategic facilities such as industrial bakeries, grain silos and generators, and move equipment to Raqqa.[33] According to a RAND report, ISIS established steady access to water, electricity, and bread within three months of seizing the area.[34]

The honeymoon period did not last. By the end of 2014, electricity levels had dropped to just a fourth of January 2014 levels, indicating serious mismanagement—especially since ISIS also controlled the Tabqa Dam.[35] Many other public services similarly withered away. Even if ISIS did impose a sense of order, it was underpinned by violence, intimidation and the brutal repression of any dissent, real or imputed.

Public executions were among the most common atrocities committed by ISIS. Hundreds, if not thousands, were killed this way. One notorious location for this was the al-Naim Roundabout in central Raqqa, which locals renamed al-Jahim—”the roundabout of hell.”[36] Here, victims were beheaded with swords, their heads planted on the iron poles of the roundabout. Others were shot dead, their bodies crucified and left hanging for days as a warning to civilians that if they opposed ISIS, they would meet the same fate.

One of the largest mass executions was conducted against soldiers based in the Syrian army’s 17th Division base. ISIS had first joined the lengthy siege of the base by opposition forces in 2013.[37] When ISIS ousted Ahrar al-Sham and Nusra from Raqqa, Assad’s air force had once again been able to use the base, leading some to argue that the two sides had, at best, a relationship marked by tactical pragmatism.[38] Others spoke of more enduring, outright forms of collaboration between Assad and ISIS.[39] But after having dealt a decisive blow to the armed opposition, ISIS returned to the siege and, on 23 July 2014, launched its operation to capture the base.

Two days of fighting, which started with suicide bombing attacks, ended with ISIS capturing the 17th Division’s headquarters. Hundreds of government troops retreated to the base of the 93rd Brigade near Ain Issa, on the Turkish border, and nearby villages. While three regiments were withdrawn, one stayed behind to cover their retreat. When ISIS entered the base, it captured and massacred the remaining Syrian soldiers, beheading many of the corpses. At least 85 Syrian army troops were killed; hundreds remained missing for years.[40]

Residents of Raqqa and Suluk described how, in the days following the attack, ISIS displayed the bodies of the soldiers and their severed heads in town squares. In propaganda videos later released by the group, children were shown examining the mutilated bodies. One eyewitness to the massacre said:

We saw so many massacres during that period, including the beheading of 70 or more young men barracked at the 17th Division base. ISIS said they were infidels who should not be allowed to live, and it sentenced them to death. Their heads were hung on the iron bars at the al-Naim Roundabout, or the “Hell Roundabout,” as we used to call it.[41]

Executions of captured soldiers also occurred outside the city. A shepherd, who used to herd his flock close to the base, remembered seeing masked ISIS fighters in the area:

They shot seven civilians and then threw them into the [water around the] waterwheel. After three days, the corpses were floating, so I buried the ones I could. On [another] occasion I saw about 15 to 20 dead bodies piled on top of each other, but I didn’t dare approach them because ISIS [fighters] were watching them. I saw several massacres; they left a deep mark on me.[42]

After taking control of the 17th Division, ISIS moved on to Tabqa Military Airport and the 93rd Brigade base in Ain Issa. The regime’s two final remaining footholds in Raqqa province, they fell on 7 August and 24 August respectively.[43] Many of the captured soldiers were taken to Raqqa. Once again, the city’s hellish roundabout was covered in the heads of ISIS’ captives.

‘They sprayed him with bullets until he was dead’: Public executions in Raqqa

Public executions were not just carried out against enemy soldiers. Under its new regime, ISIS also enforced strict religious compliance through specifically appointed imams and Shari’a courts. The practice of magic was punishable by death, as was insulting the Prophet (Peace Be Upon Him). Fear of punishment spread quickly through society, according to one man from Raqqa:

You had to stay quiet at work and be careful about what you said. A mistake or a slip of the tongue was considered blasphemy. My nephew [M.] was killed because he was moody. He used to swear, curse and use insults a lot. I warned him about it, telling him it could get him beheaded.[44]

ISIS had no qualms about killing children either:

One day, an ISIS patrol raided the Rumaila area, and they took about 20 people. Among the people detained by ISIS were my brother’s sons, [M. and A.] along with a third person called [H.]. Everyone they detained was under 18 years’ old.

There were lots of rumours about why they were detained. We heard reports that [ISIS] arrested them because someone filmed a video of them blaspheming, while others said they were working for the [Coalition]. Almost three weeks later, ISIS executed [H.] and crucified his body on 23rd February Street, so everybody could see it. He was executed by firing squad.[45]

Preoccupied with establishing totalitarian control over the city, the new rulers of Raqqa saw spies and agents everywhere. One witness talked about seeing his brother executed at the al-Naim Roundabout:

After midnight, a group of armed [ISIS] fighters burst into the house, went into [my brother’s] room, and took him from his bed. He wasn’t wearing anything at the time. His wife screamed, and one of his brothers ran after them and gave them his clothes to cover himself with.

They took him to prison. As with everyone they sentenced to death, they forced him to read the entire Quran. He completed it in fifteen days. Then they took him to the al-Naim Roundabout in Raqqa, shouting that he was an agent of the Nusayris, meaning the Syrian regime.

Then they cut off his head and hung it on the wall of the roundabout. His body stayed on the ground where they had thrown it. They kept the head there for more than a day to terrorise people.

When we found out that he was at the roundabout, his brothers took their guns and went there. They had an argument with the ISIS fighters guarding the place where the heads were, and they managed to overpower them and retrieve the body and the head. They fled immediately to go and bury him. ISIS caught up with them and started firing at them, but no one was injured. ISIS lost their way. After that, we buried him.[46]

It was often of no consequence if charges of spying were true or not. Rubbing a well-connected ISIS member the wrong way could have terrible consequences, and often led to people being denounced as “agents.” There was no need to provide evidence of the allegations. For example, a mother recounted her son’s killing after he was accused of working with the PKK:

My eldest son, [H.], 17, was arrested several times on various charges. The last time, he was accused of being a PKK member. They raided our house and detained him.

[H.] hated ISIS. He insulted them to their faces. He didn’t respond to their orders. I sent him to Turkey twice, to try to get him away from ISIS, but he refused to stay there and came back.

[After H. was arrested,] I repeatedly tried to get information about him at their headquarters in Raqqa, near the White Garden. But they wouldn’t give me any information. One time I went, they threatened to cut off my head if I asked again. They kept him in detention for two months or more. Then they summoned me to see him. They told me: “Come and see your son, because he will be executed.”

[…] after severely torturing him, they carried out [H.’s] death sentence at the al-Jazra junction in Raqqa. They sprayed him with bullets until he was dead. There were other young men with him who were also executed on the same charges.

We were devastated by his killing. He was completely innocent. My health deteriorated, and I started taking medicines and sedatives. Whenever I remember seeing his body hanging there, my heart tightens up with pain.[47]

Even then, ISIS fighters were not done with the woman and her family:

Even after my son was killed, they kept harassing me because I’m Kurdish and from Ain Issa. ISIS accused me of being a non-Muslim. They restricted my freedom of movement.

A group of foreign fighters came to our house with their wives several times, and offered to marry my daughters in a threatening way. They offered big sums of money. When I refused, I was accused of being an agent [of the PKK] and I was flogged more than once.

All this was meant to pressure me to marry my daughters to them. After repeated visits by the women, I smuggled my young daughters to [a neighbourhood on the northwestern edge of Raqqa city] and got them married to old men from Raqqa, from the Albu Hamid clan, out of fear of ISIS.

[Another] woman was also tortured in front of me for refusing to follow their orders. She was pregnant and the torture gave her a miscarriage.[48]

Many of the killings were videotaped and distributed. One of the most notorious examples was the burning alive of Jordanian fighter pilot Muath Youssef al-Kasasbah on 3 January 2015. Kasasbah had been captured by the group just over a week earlier, after his F-16 fighter jet came down during a mission targeting ISIS positions in northern Raqqa. ISIS made a high-quality, Hollywood-style film of Kasasbah’s execution. They walked the pilot at gunpoint through rubble caused by US-led Coalition airstrikes, placed him in an iron cage, and dressed him up in an orange suit like those worn by US detainees at Guantanamo Bay and the Abu Ghraib prison in Iraq. Then they burned him alive.[49]

Such a video had an obvious international propaganda purpose. But less high-profile killings were also recorded. A woman from Raqqa described the agony of seeing her husband’s execution this way:

The son of our neighbour, who had tried to get information about my husband, brought me a video and put it on the computer. It showed my husband’s execution.

It was done by an [ISIS] fighter wearing a camouflage suit and a mask, with only his eyes clear and the slogan “there is no god but Allah” on his head. He was carrying a meat cleaver. My husband was blindfolded, and his hands were cuffed behind his back. Then the [ISIS] fighter cut off his head with the blade. [50]

Raqqa’s mass graves

ISIS dug mass graves to dispose of thousands of bodies killed in executions or massacres. Around 30 mass graves have been uncovered since ISIS’ defeat in Raqqa in 2017, estimated to contain between four thousand and 6,300 bodies.[51] Many of these graves were located in Raqqa city or surrounding areas.

One of the biggest mass graves discovered was in a cemetery in the city’s Panorama district. This contained at least 900 bodies.[52] Another, in the agricultural suburb of al-Fukheikha, was initially thought to hold the remains of as many as 3,500 people.[53] Other mass graves were found at the Old Mosque and its garden; the Children’s Park; the White Garden; the Jumaili Building Garden; the Crown; Western al-Salhabiya; the brick factory; civilian houses in the al-Bedu neighbourhood; the al-Rashid area, as well as at least a dozen other sites.[54] In al-Amrat, a mass grave likely containing the bodies of hundreds of missing Syrian army soldiers from the 17th Division was found.[55]

Local teams have begun exhuming bodies, assigning each an identification number, and storing them securely. Most of the recovered bodies are reburied at the public al-Bai’a Cemetery, five kilometres east of Raqqa. Nevertheless, resources are inadequate. Human Rights Watch warned that the ‘sites are not being protected in accordance with international best practices, thereby damaging families’ chances of identifying their loved ones.’[56] The lack of resources may also prevent more mass graves from being uncovered. In comparison, similar work by Iraqi authorities, supported by the United Nations Assistance Mission for Iraq and the OHCHR, had already documented 202 mass graves by the year 2018.[57]

ISIS also dumped bodies into a deep pit called al-Hota. This was a huge natural gorge of unknown depth in northern rural Raqqa, 65 kilometres from the city, near the town of Suluk. It was a main regional stronghold for Jabhat al-Nusra before it was seized by ISIS; Nusra and other armed groups, including the al-Qadsiya Brigade, had already turned the hole into a mass grave for Syrian soldiers.[58] After the fall of Raqqa, activists estimated that 200 soldiers and pro-government militia fighters had been thrown into al-Hota.[59] When ISIS was in sole control of Raqqa, it continued using al-Hota for executions; it also threatened people with being thrown into the pit. Al-Hota’s edges were reportedly scattered with bodies.[60]

Similar holes exist at al-Wusta al-Shamia (Habit al-Nuk), 60 kilometres south of Raqqa and northeast of al-Sukhnah, and at al-Hota al-Soghra (Twal al-Aba), which lies 45 kilometres northeast of Raqqa city. Residents estimated that nearly a hundred victims’ bodies were dumped in the latter, including civilians and even members of ISIS executed for “apostasy.”[61]

It remains unclear just how many people were disposed of in the three gorges. The research team was unaware of any attempts to extract the bodies dumped in al-Hota, due in large part to the difficulty of entering the pit and the lack of equipment to extract the bodies.

‘Prepare yourself for your punishment’: Floggings and amputations

Raqqa, perhaps more than any other Syrian city, saw arbitrary arrests, torture and degrading treatment of prisoners. Harsh sentences, which ISIS justified under Shari’a law, were thought to deter people from committing crimes. There was corporal hudoud punishment, including amputations of hands and feet, throwing people from tall buildings, and stonings and floggings in public squares. Floggings could be administered for something as simple as the “crime” of smoking, as one man recalled:

I was arrested several times for smoking. They flogged me and fined me 10,000 Syrian pounds. That was before the displacement of the Kurds from Raqqa, so in 2014. It was around the beginning of Ramadan. The people who did that to me were foreign fighters, they were not from Raqqa.[62]

Those who resisted arrest would not be treated with compassion. A mother described what happened to her husband and daughter when they did not comply:

ISIS fighters came to our house to take my husband to prison. I asked them: “What do you want from him, why are you taking him?”

One of them shouted at me: “Shut up!”

When my husband objected, one of the ISIS fighters hit him on the head with a weapon until he was unconscious and covered in his own blood. My daughter screamed, and one of the ISIS members hit her hard against the wall. She fell, hit her head and fainted. She was bleeding from her head. We took her to the hospital; she was in intensive care for three days.

My husband stayed in their prison for about two months. They interrogated him, but he knew nothing. He is a simple person.

When they released him, he got sick with a neurological condition. He started to behave inappropriately toward us. He cursed and swore and insulted us, and he even hit his daughter. He grabbed a teapot and hit her with it, burning her leg.

That was on top of the blow she received from ISIS. So now she [too] has a nervous condition. She started wetting herself at the age of 12. She has since started walking again and her situation has improved a little.[63]

Victims said there was no presumption of innocence—rather, a presumption of guilt—in ISIS’ system of arbitrary justice. The punishment for haraba, a word that translates as “banditry” but is used to signify theft, was amputation. A victim that suffered this punishment told us:

On the 17th day of Ramadan, a man called Abu Ramadan came in and told me: “Prepare yourself for your punishment.”

I asked him why. He said: “Because you’re a thief.”

I said I wasn’t.

He said: “Well, that’s what the judge ruled.”

Of course, I asked to see the judge for my hearing before the 17th of Ramadan. They took me and another person on a motorbike.

I asked him: “Is there an anaesthetic [given]?”

He said: “Yes, there is, and paramedics and security personnel.”

We got there, but there was no anaesthesia. He tied my fingers with a thread and pulled them, placed the sword, and hit it twice with the hammer, and my hand was cut off.

I felt the pain, but I didn’t make a sound, because I was so resigned to my reality.

But then, five ISIS members pinned me down and put my feet on a table as well. Then they hit me three times, and on the third strike they cut my metatarsus. Then one of them grabbed my feet and tore them with his hands, and I started screaming in pain.

Then they took me to the hospital. Of course, their mission was to carry out the punishment, then take the victim to the hospital until he recovered from the anaesthesia. Then they have nothing to do with it after that. I stayed in the hospital until 8 pm.[64]

‘I spent so long sitting underground’: Arbitrary detentions and torture

Raqqa was home to several dozen ISIS prisons, many with reputations as horrific atrocity sites. Among the worst were the prison in the al-Rashid Municipal Stadium and the Point 11 prison, near the al-Hadhri restaurant.

A military stronghold in Raqqa, the Point 11 prison, also known as the “Black Stadium,” was the most prominent of all security prison.[65] It primarily housed security detainees, including YPG members arrested for the purpose of prisoner exchanges but also civilians arrested by hisba forces on non-security-related charges.[66] Some prisons were smaller, makeshift facilities in basements or houses.

The shepherd quoted above, who had earlier seen the executions at the 17th Division military base, was later detained in the Children’s Hospital, another prominent prison site:

At the sheep market, ISIS appointed an informant. One day, they arrested me. They came to the sheep market, detained me and gathered a group of us at an apartment in al-Firdous.

We were blindfolded. They kept us in the basement of the Children’s Hospital for 55 days. We did not see the sun [for all that time].

When I was interrogated, they asked me: “Why didn’t you take a Shari’a course…don’t you like us?”

I told them that I didn’t have time for it, and they beat me while I was blindfolded.[67]

Forms of physical and psychological torture were common in ISIS prisons, leaving visible marks on prisoner’s bodies. A former detainee described their degrading treatment:

They held me for seven months. They transferred me from one prison to another, including the Children’s Hospital, which they used as an underground prison, and the Jumaili building, the White Garden [near the al-Baik restaurant] and apartments in the al-Bedu district.

They hung me by my hands for seven days, until my feet swelled up. When they interrogated me, they accused me of being a shabeeh [regime loyalist]. Then they accused me of being an American agent. They accused me of all sorts of things. After six months, a panel of their “judges” came and accused me of apostasy. They said I should be executed, and not given a Muslim burial.

They threatened me with punishment and took me to a room where everyone was wearing orange. They dressed me in orange too. They shaved my beard and the hair on my head. Every day, they took two or three people out to execute them. Then they would bring back their clothes, stained with blood. They did all this to make us terrified.[68]

Eventually, the man got out; many others suffered a different fate. Attempting to escape could lead to severe punishment as well. The man who later suffered the amputation, described above had earlier attempted to escape:

One day we were digging to try to break the prison wall and escape, but we were discovered. There were 35 people in solitary confinement at the prison, in cells about a metre long and a metre wide. They moved us to the solitary cells as punishment.

They wanted to know which of us had started digging to try and escape.

Our punishment was to be flogged with a plastic rod. Everyone received a different number of lashes: there wasn’t a specific number, it depended on the mood of the person doing it. If one of them got tired, another took over, so they could flog the entire prison population.[69]

ISIS’ abuses in detention also left less visible traumas. A resident of Raqqa said:

My mental state is really bad, and it gets worse whenever I remember those events. I cry and I can’t express myself. It’s like it was a nightmare.

My whole life changed. I’ve withdrawn from people. I hate sitting in any room because I spent so long sitting underground. The prison was big. It had lots of mirrors, so now when I see myself in the mirror, it triggers trauma. For two months after I was released, I felt like I was still in prison.

My wife left me. I was in a bad way mentally. My hair fell out from the fear and the disease in the prison. I got diabetes. Now I am traumatised when I think about it. I was subjected to severe physical torture that I will never forget for the rest of my life.[70]

According to the Commission of Inquiry on Syria appointed by the UNHRC, the conduct of torture as part of the attacks on the civilian population in Raqqa amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity.[71]

The Christian exodus

As in other parts of ISIS’ self-proclaimed “caliphate,” Raqqa’s minorities were systematically targeted. Displacement resulted not only from the violence but also from discriminatory “laws,” policies and taxes levied against ethnic or religious minorities. On 23 February 2014, ISIS published a statement addressing Christians, stating that they would have to pay as much as 17 grams of gold annually in the jizya, the tax on non-Muslims living under Islamic rule.[72]

Nusra and the FSA had earlier targeted Christians in the area, such as Corporal Toni al-Mallouhi, the former mayor of al-Mansoura; ISIS vowed to execute Mallouhi but later released him when he converted to Islam.[73] Another prominent event was the abduction of Father Paolo Dall’Oglio, an Italian Jesuit priest and peace activist who had served for three decades at Deir Mar Moussa al-Habashi, a sixth-century monastery 80 kilometres north of Damascus. The Syrian government had ordered Dall’Oglio to leave Syria in 2012 due to his meeting with members of the opposition and criticising the government’s response to the uprising. He later re-entered the country and was kidnapped by ISIS in Raqqa on 29 July 2013.[74] There were conflicting reports that Father Paolo was still alive, and at one point he was said to be used as a bargaining chip by ISIS.[75] He remains missing today.

By the time ISIS took full control over Raqqa, most Christians, many of whom had come to Raqqa during the Armenian exodus, had already left the city.[76] Between September and October 2013, ISIS attacked three churches in Raqqa province including the Armenian Orthodox Church of the Martyrs in Raqqa city. ISIS removed the crosses, hung black flags from the façade and turned it into an Islamic centre.[77] In October 2013, the group also burned down an Armenian church in Tal Abyad.[78]

As it seized more territory in northeast Syria, ISIS continued to attack Christians and their places of worship. At the end of 2014, only 23 of Raqqa’s 1,500 Christian families reportedly remained.[79] Those who fled and wished to return would be asked to convert or pay the jizya. The research team made efforts to find victims and witnesses from Raqqa’s Christian community, but they were unable to locate any, suggesting that Christianity had (nearly) been eradicated from formerly ISIS-held territories in Raqqa province.

Shi’a Muslims also faced mass displacement from Raqqa. The Owais al-Qarni mosque, built as a Sufi shrine, was destroyed on 31 May 2014 along with seventh-century tombs in the city.[80] There would be no place for Shi’a Islam in ISIS’ capital.

‘They were not the sort of people you could negotiate with’: Forced displacement of Raqqa’s Kurds

ISIS launched large-scale operations against Raqqa’s Kurds. A report by the UN Commission of Inquiry documented these attacks, stating that ISIS began to forcibly displace Kurdish civilians from towns across Raqqa province in July 2013; it demanded Kurds leave Tal Abyad or be killed, and thousands of families fled on 21 July. Arab Sunni families were resettled in Kurdish homes, forever changing northeast Syria’s demographics.[81]A resident of Raqqa recounted the forced displacement of the Kurds:

They issued a decree that the Kurds had to leave. They made the announcement at six o’clock in the morning on the mosque’s loudspeakers, for ten minutes. I don’t know what their reason was, or what we had done to them so they would make such a decision. But we had to do what they said and leave all our possessions, against our will.

They were armed, and they were not the sort of people you could negotiate with. They confiscated my food warehouses and my harvests, such as cumin and barley, as well as my livestock. My brother’s household appliance shops in Tal Abyad were also seized. All this gave them a source of income, which they called “spoils of war.” [They] believed that what they were doing was halal.[82]

Fighters systematically looted and destroyed Kurdish property. A Kurdish resident spoke about the impact this had on the Kurdish community.

We lived in fear. They saw us as infidels who did not know God. I was afraid to leave my house. My son was sick, but I was too afraid to take him to the doctor. They did not just harass us, confiscate our property and subject us to insults and humiliation; they also forcibly displaced us later, just because we’re Kurdish.

I remember then that they announced through the mosques that we should all leave our homes and that we would be deported to Tadmur [Palmyra]. But suddenly, after they deported us, they took us to the Baghdik area in rural Kobane. They deported the entire Kurdish community from our neighbourhood. We all left with just the clothes on our backs.

We couldn’t do anything to resist them. I returned after a while and found my house almost destroyed, and all my belongings stolen. They even stole a cow I kept in my barn; I used to sell its milk for some extra money. I repaired some things in my house and rebuilt the destroyed parts, but later they rigged it with explosives and destroyed it again.[83]

Many others told a similar story of displacement and property theft. An Arab man from Raqqa recalled how a well-off Kurdish man went home to his neighbours before leaving the area. As the days went by, ISIS began searching for the homes of Kurds. They put blue signs on them saying “Kurdish infidel.” Depending on the state of the house, they would either hand it over to ISIS foreign fighters and their families or local fighters (if the property was more modest). Because the well-off Kurdish man’s house was said to be beautiful, it was taken over by a foreign fighter. [84]

A Kurdish woman went through a similar ordeal—all while pregnant:

They came to take our house, saying that since we were Kurds, we must work with the PKK. A Tunisian ISIS emir, who spoke in classical Arabic, came into the house with female [ISIS] members. He looked around the house and our belongings. The ISIS commander gave us fifteen days to leave.

I was pregnant, tired, and terrified. I went to the hospital and saw nine severed human heads on the al-Naim Roundabout. The sight traumatised me. It’s still with me today. I had a premature birth.

Before we were displaced, all I took from the house were my children’s clothes. When I went back to try to take my belongings, I was kicked out and threatened with imprisonment. They did not give me any of my belongings. The Tunisian emir lived in the house with two women.

Then we went to my uncles’ house. Two weeks later, they broadcast though the mosques that all the Kurds had to leave. We were deported to Jalabiyya in rural Kobane. Then we lived in a horse stable for four months. Our lives were really hard there.[85]

The UN report concluded that “as a widespread and systematic attack against the Kurdish civilian population, these acts amount to the crime against humanity of forcible displacement.”[86]

‘Since you are pregnant, I’ll only give you 14 lashes’: Violations against women and girls in Raqqa

ISIS’ hisba forces enforced strict rules about what women could wear and where they could go, employing an iron fist during its regular patrols throughout Raqqa. If women violated the rules, judges levelled severe sanctions against them including flogging or imprisonment. One woman described how she was detained for improper dress:

I was going to buy medicine for my mother, who was sick. I was in full Islamic dress, but when I went down the stairs of our building, I lifted my abaya [full-length gown] slightly so I wouldn’t trip over it. My foot had been injured in a bombing.

An ISIS fighter saw me and came over. There was a hisba patrol car nearby. They detained me and kept me in their custody from ten in the morning until five in the afternoon. I was given ten lashes and forced to undergo a Shari’a course. They confiscated my ID until I had passed the course. I was so afraid of them, and I’m uneducated, but to finish this course, you have to pass their test.

I saw a lot during those hours at the hisba base. There were stonings and torture. Some women were waiting to undergo death sentences.

There were women who were detained by the hisba for months for nothing, and with no charges against them. It was terrifying, difficult and tiring. During those hours, I felt as if I had entered another world.[87]

Unmarried women who had reached puberty posed a particular threat to ISIS’ social order. Many were arbitrarily arrested on suspicion of mixing with the opposite sex. In June and July 2014 alone, eight women were stoned to death in Raqqa on charges of adultery. [88] Widows were supposed to remarry, as this woman witnessed during her detention by the women’s hisba force:

They took us to the al-Jumaili hisba headquarters and kept us there for three days. I remember that they detained me on a Tuesday, and I was released on a Friday. They gave me 14 lashes with a whip. The person who flogged me was called Abu Ali al-Tunisi. He told me: “Since you are pregnant, I’ll only give you 14 lashes.”

They put us in a room. We were about 22 women, and most of the charges were for injecting [heroin]. One of them had been widowed and they wanted to force her to marry an ISIS fighter. She refused, so they locked her up. Another was accused of being an infidel because in an argument with her mother-in-law she had blasphemed. Her husband was an ISIS emir, so he reported on her, and they arrested her.

There were many other stories. There were young girls there who they’d tried to recruit but had refused, so they locked them up.[89]

Adolescent girls as young as 13 were seen as a commodity with which ISIS could reward its fighters and attract more young men into its ranks. This stirred residents’ fears that they would be forced to hand their girls over for marriage to ISIS fighters. The situation prompted many families to marry their daughters off to other men, to prevent them from ending up being forced to marry into ISIS. One victim described how this fate—forced marriage—befell his family after his brother’s children were killed:

My brother [H.] had sons, including [M.], who sold tobacco on the black market for a living. He used to buy large quantities from big smugglers. In early 2015, he was arrested and taken to prison, beaten for a week with hosepipes, and tortured in terrible ways. Then [his other sons], who were born in 2000 and 2002, were summoned, beaten and accused of being agents of the Kurds. They were all executed on the same day. They executed [M.] in the Sawami’ district.

When we found out, we couldn’t do anything. It was terrible for all of us. But my brother [H.] was the worst-affected. His sons had been executed. He lost his mind. He didn’t know what was going on around him anymore. I would often go to work and people would call and tell me he was in Sawami’ [and] I would have to fetch him and bring him home. When I went out, I was afraid to leave him alone in case he committed suicide or harmed himself.

A few days passed and they came back to harass us again—this time demanding to marry [H.’s] daughters, [S. and T.]. At first, I refused, and kicked them out of the house. Several times, they accosted me at the vegetable market and pressured me to accept, but I still refused. In 2016, two hisba patrols arrived, including young men and women, and arrested the two girls.

One of the girls was born in 1997 and the other in 1998. [ISIS] married [T.] to a Tunisian, and [S.] to a young local ISIS member from al-Qattar Street in Raqqa. That’s where they took the girls. I asked around to find out about the men and find my nephew’s daughters. I found out that one of them was from al-Qattar Street. I went and argued with them. I saw his brother and said to him: “Would you like it if an ISIS member came, took your sister against your will and married her?”

He said: “No, but that’s the situation, whether we like it or not.”

I fought with many people over the girls, but I couldn’t do anything, because they were ready to charge us and take retribution.[90]

According to the UN Commission of Inquiry, such forced marriages were violations of international humanitarian law and acts that amount to war crimes of cruel treatment, sexual violence, and rape.[91] Those who were married to ISIS fighters often ended up in abusive and violent relationships. A woman from Raqqa related to the research team the physical torture she was subjected to by her husband:

Before ISIS came, I wasn’t married. I lived a decent and comfortable life with my family. I had no sisters and eleven brothers. I was in school until the sixth grade, but after that, my family stopped my education.

A young man proposed to me through my brother’s wife when I was 15. He was from the al-Bureij area. Right from the start, there were problems. My brothers didn’t accept him. They weren’t convinced, as he was an ISIS member. They said: “God knows what he might do to you down the line.”

However, in our area, the father has the final say over his daughter’s marriage, and what he says goes. I couldn’t break my father’s word. And so, we got married.

A little while later, my husband started beating me. I was pregnant with my first son. We had a disagreement because I got sick, and I was worried. I had just gotten pregnant. But he wasn’t convinced that I was pregnant. I asked him if we could go to the doctor to get tested. I was sure that I was pregnant. But he said he wasn’t convinced. He wanted to bring my mother to the house. When she came, he started cursing me and saying there was no pregnancy. He hit me on the back, and I started bleeding. He hit me with a cane. He hit me again and the bleeding got worse. Thank God the child didn’t come out. God saved my pregnancy.

My husband used to treat me like ISIS fighters treat women, because he would sit with his brother and his friends, who were also members. He learned from them how they thought women should be treated. He would say to me: “You should be flogged. I want to take you to the women’s hisba so they can re-educate you.”

He was often violent towards me. He would force my head underwater and take it out. He would hold a knife against my body. He would throw food over my head. I would put my hand on my face out of fear and to protect my face.

My hand developed a tremor, which I still have. On one occasion, he beat me while we were with his family because I washed his shoes. He threw me on my back, tied my hands and started hitting me on my face.

I later discovered that he had a neurological condition. I was good at reading, and at one point he told me to give him his medicine from the cupboard. A piece of paper came out with the medicine, and there was a report saying he had a nervous disease. It seems he was cutting himself with a razor blade, and he wanted to do the same to me on top of all the beatings and other violence.

When we were first married, he taught me to smoke. I started smoking with him. Then, after teaching me, he started asking me: “Why do you smoke?” and telling me to stop it. I told him I was used to it, and I couldn’t suddenly quit.

When he saw me smoking a cigarette, he brought a gun and hit my hands with the butt of it. Then he loaded it and put it between my eyes. I screamed and put my son on my lap. He threw away the gun, grabbed a mop and beat me until my face and chest were covered in blood. My son was on my chest, and even he was disfigured from the blood and the beatings.[92]

In Raqqa, like in the other areas under ISIS’ control, slavery was also common. Enslaved women and girls were predominantly, although not exclusively, Yazidi women and girls. While captured, Yazidi men were killed, the women kept as slaves and their children were taken to be “re-educated” in ISIS’ ideology. In Raqqa, these captives were often presented to senior ISIS figures, especially foreign commanders. Local fighters also bought captives from the slave market. The Yazidis were kept at the Abu Qubi’ Hotel, 10 kilometres west of Raqqa, and at the Suhail Habib Farm in Kasrat Faraj, five kilometres south of the city. The children were kept at the Ba’athist Vanguard Camp on the New Euphrates River Bridge.

‘The children only knew ISIS anthems’: Violations against Raqqa’s children

Once under ISIS control, Raqqa’s schools were closed. Instead, so-called katatib and Shari’a teaching circles in mosques were introduced. The new educational programme was successful in instilling ISIS’ interpretation of Islamic values in the students, as a music teacher recalled: “I returned to my previous job as a music teacher, but it had become a widespread belief that music was haram, even among the parents. The children only knew ISIS anthems.”[93]

In Raqqa, ISIS gathered children for screenings of videos showing massacres of Syrian government soldiers.[94] One man recalled how his son’s education was essentially a precursor to military training:

My son could not complete his education and became ignorant because of [ISIS]. When I took him to school during ISIS rule, the teacher was teaching him how to carry a weapon. They would train them on wooden guns […] and promised them a real weapon after a week.

They also took advantage of children and their innocence to find out what we do at home, such as smoking and other things. I withdrew my son from school immediately after that. They asked me why. I told them that my son was mentally ill, and I didn’t want to leave him alone. Their curriculum was Islamic law and theology […] but it had nothing to do with Islam.[95]

Children were expected to spy on their families and communities. Hundreds of other children, reportedly between the ages of five and 16, were trained for combat roles near Tabqa.[96] Yazidi child soldiers were taken by ISIS to a training camp in northern Raqqa.[97] Children also took active combat roles: ISIS videos from Raqqa, seen by the research team, showed children as young as five years’ old executing detainees.

‘We had to leave their bodies under the rubble for two months’: Civilian casualties during anti-ISIS operations

By late 2016, the SDF, backed by the US-led Coalition, had already defeated ISIS in Kobane, largely expelled the group from Hasakeh, and liberated Manbij. The campaign to dislodge ISIS from Raqqa started in earnest on 6 November 2016.[98]

Initially, the campaign focused on Raqqa’s northern countryside. When this area was secured, a lengthy battle around Tabqa ensued to the west, while to the east the SDF advanced on the highway connecting Raqqa and Deir Ezzor. This cut off the last major road out of ISIS-controlled Raqqa city.[99] By early June, the SDF and the US-led Coalition had taken control of Tabqa and al-Mansoura, to the west of the city. Then, the battle for Raqqa city began.[100]

The fight for Raqqa was not just strategically important; it also carried immense symbolic value. Fought concurrently with the battle for Mosul, it was the last major city in Syria fully under ISIS control, containing the group’s command-and-control centres and housing many of its top leadership. Expelling ISIS from its self-proclaimed capital was expected to put a serious, if not fatal, dent in the ambitions of the so-called “caliphate” to maintain, control and govern territory. The SDF dubbed it the “Great Battle.”[101]

Raqqa was encircled and besieged by the end of June 2017, with as many as four thousand ISIS fighters trapped inside the city. The next month saw creeping advances; after a hundred days of battle, the SDF controlled more than two-thirds of Raqqa and nearly all of its Old City.[102] The last remaining ISIS holdouts, in the north of the city and around the al-Naim Roundabout, where so many had been executed, were fought over intensely. These areas were heavily mined and boobytrapped. SDF advances, relying on airstrikes by the US-led Coalition, were slow and painstaking.[103] ISIS had ordered that no one could leave, seeing the value of citizens as human shields to protect them from airstrikes. ISIS snipers were prevalent. Those who did flee by car or boat risked being taken for scurrying ISIS fighters. One woman recalled her experience trapped in the besieged city:

They ordered us to leave our homes, saying the area had become a frontline. We went to the al-Kahraba district. There was bombing day and night. The al-Bedu district was being shelled and besieged.

It was us, my cousin’s family, and another family. We suffered so much. First, my brother [A.] was wounded. Then they kept us all under siege in al-Bedu and used us as human shields.

My brother was in the bathroom. There was heavy shelling. We were sitting in the kitchen. We told him to come and hide with us, for fear of the shelling. When he came to sit with us, a shell landed on us, and he was hit in the foot. We had no means of transportation at the time. Our neighbour took him to the National Hospital, and they amputated his leg.

Four days later, we decided to try and flee. My brother [K.], who had crossed the Euphrates to the liberated areas, came back to Raqqa. When we asked him why, he said: “How can I leave my injured brother here and escape on my own?”

My brother left with a group of people, so he could show them how to escape [ISIS]. Then one of the people with them came back and said: “Everyone with us died.”

When we asked him about my brother, he said: “Your brother’s legs were blown off by landmines left by [ISIS].”

When we went to the emergency ward, we found everyone dead. We helped the son of a person who was with them, and his wife. But we found that [K.] had bled to death. My brother had also donated blood to my other injured brother, [A.].[104]

At long last, around 300 to 400 remaining ISIS fighters brokered a deal to leave the city.[105] With 400 hostages as human shields, ISIS fighters and their families—including dozens of foreign fighters and some of the group’s most notorious members, including ISIS intelligence chief Abu Musab Huthaifa—made for Deir Ezzor, where ISIS still held territory.[106] After four months of intense fighting, the SDF declared Raqqa liberated on 20 October 2017, vowing to include it in a federal, democratic northeast Syria governed by the Autonomous Administration.[107]

The price of Raqqa’s liberation was immense. As negotiations over the surrender of ISIS fighters were ongoing, the US-led Coalition carried out heavy bombardments. ISIS members said these had killed 500 or 600 fighters and their families.[108] While such numbers may have been exaggerated, there were undeniably high numbers of civilian casualties. A father spoke to the research team about the airstrikes during the battle, which killed many of his family members, in the final month of the offensive:

During dawn prayers, warplanes came and started bombing the area we were in. They bombed the building where we lived. There were another five buildings next to it. Forty-five bodies of people who were killed in the bombing were identified. They included five members of my family who were killed before my eyes.

I’ll never be able to forget that day.

The buildings were next to the al-Maari School. Everyone killed was a civilian. There were no ISIS fighters, unfortunately; they had run away. They were cowards, and as soon as they [heard] warplanes, they got into their cars and fled. We stayed, and we were killed. My children—[A.] who was 27; [AM.] who was 18; [R.] who was 17; and [H.] who was 15—as well as my sister [Z.], who was 65. They were all killed.

We had to leave their bodies under the rubble for two months. There was nobody to help us get them out. Everyone else who was there was injured in one way or another.[109]

According to documentation by Amnesty International and Airwars, the Raqqa campaign killed more than 1,600 civilians.[110] A joint report by the two organisations outlined the impact of thousands of airstrikes, primarily carried out by the US but also France and the UK, and over 30,000 artillery strikes by the US military—the equivalent of one artillery strike every six minutes for four months on end. The US-led Coalition had referred to the campaign as ‘one of the most precise air campaigns in history’. The Amnesty and Airwars report observed that the aerial campaign had turned Raqqa into the ‘most destroyed city in modern times.’[111] De-mining groups also said Raqqa was left as the ‘most contaminated city in the world’ due to mines and unexploded ordnance dropped from the air.[112]

The aftermath

While the battle for Raqqa still raged, tribal leaders and prominent figures from Raqqa met in Ain Issa in April 2017 to discuss the future of Raqqa province. They established a civilian council to govern Raqqa city post-ISIS, made up of Arab, Kurdish and Turkmen representatives. Afterwards, the city would later become the headquarters of the Autonomous Administration.

However, the task at hand for the new, post-ISIS authorities was monumental. Raqqa’s economy was devastated. Mine and rubble removal operations started, as did early attempts at rebuilding infrastructure destroyed during the conflict. Gradually, some progress was registered. A hospital reopened. Some residents returned to face the destruction.

ISIS was down, but not out. It would be more than a year before its final holdouts in Deir Ezzor would be conquered. Meanwhile, the group continued attacks in Raqqa—including car bombs, assassinations and occasional firefights with the SDF, with ISIS sleeper cells biding their time and hoping for a chance to plot their return.[113]

But Raqqa, once the capital of ISIS’ so-called “caliphate,” lays in ruins.

Footnotes

[1] Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics, ‘Syria Population Census, 2004’ (Ar.) (n.d.) <https://web.archive.org/web/20151208115353/http://www.cbssyr.sy/General%20census/census%202004/pop-man.pdf> accessed 17 August 2023.

[2] Map Action, ‘Syria District Maps : Ar-Raqqa’ (4 July 2016) <https://maps.mapaction.org/dataset/217-2788/resource/a3047113-c3e8-4fc0-8ad6-8b6d96c07f91> accessed 19 August 2023.

[3] Alexander Dziadosz and Oliver Holmes, ‘Special Report: Deepening ethnic rifts reshape Syria’s towns’ Reuters (21 June 2013) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-syria-rebels-sectarianism-specialrepo-idUSBRE95K08J20130621> accessed 19 August 2023.

[4] Individual testimony #34, focus group session 3.

[5] Individual testimony #99, focus group session 7.

[6] Individual testimony #97, focus group session 7.

[7] Individual testimony #143, focus group session 4.

[8] Nate Rosenblatt and David Kilcullen, How Raqqa became the capital of ISIS: A proxy warfare case study (New America, July 2019) p.13 <https://d1y8sb8igg2f8e.cloudfront.net/documents/How_Raqqa_Became_the_Capital_of_ISIS_2019-07-26_134456.pdf> accessed 19 August 2023.

[9] Associated Press, ‘Protests, gunfire in Syria as Eid al-Adha begins’ (CTV News, 6 November 2011) <https://www.ctvnews.ca/protests-gunfire-in-syria-as-eid-al-adha-begins-1.722106> accessed 19 August 2023.

[10] Rosenblatt and Kilcullen, p.13.

[11] Kadir Celikcan, ‘Syrian rebels extend grip on Turkish border’ Reuters (19 September 2012) <https://www.reuters.com/article/syria-crisis-idUSL5E8KJ8NR20120919> accessed 19 August 2023.

[12] Matthew Barber, ‘The Raqqa Story: Rebel Structure, Planning, and Possible War Crimes’ (Syria Comment, 4 April 2013) <https://www.joshualandis.com/blog/the-raqqa-story-rebel-structure-planning-and-possible-war-crimes/> accessed 19 August 2023.

[13] Barber, Syria Comment.

[14] Firas al-Hakkar, ‘The Mysterious Fall of Raqqa, Syria’s Kandahar’ Al-Akhbar English (Beirut, 8 November 2013) <https://web.archive.org/web/20171019062932/http://english.al-akhbar.com/node/17550> accessed 19 August 2023.

[15] Rosenblatt and Kilcullen, pp.16-19.

[16] Barber, Syria Comment.

[17] Rosenblatt and Kilcullen, pp.19-23.

[18] Described in more detail in the introduction of the report.

[19] Interviews with Raqqa residents, April and May 2023.

[20] Interviews with Raqqa residents, April and May 2023.

See also: Alison Tahmizian Meuse, ‘In Raqqa, Islamist Rebels Form a New Regime’ Syria Deeply (16 August 2013) <https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/syria/articles/2013/08/16/in-raqqa-islamist-rebels-form-a-new-regime> accessed 19 August 2023.

[21] Christoph Reuter, ‘Secret Files Reveal the Structure of Islamic State’ Der Spiegel (18 April 2015) <https://www.spiegel.de/international/world/islamic-state-files-show-structure-of-islamist-terror-group-a-1029274.html> accessed 19 August 2023.

[22] Rosenblatt and Kilcullen, p.25.

[23] Al-Hakkar, Al-Akhbar English.

[24] Interviews with Raqqa residents, April and May 2023.

[25] Meuse, Syria Deeply.

[26] Al-Hakkar, Al-Akhbar English.

[27] Rosenblatt and Kilcullen, p.26.

[28] Reuter, Der Spiegel.

[29] Al-Hakkar, Al-Akhbar English.

[30] Rosenblatt and Kilcullen, p.29.

[31] Al-Jazeera English, ‘ISIL recaptures Raqqa from Syria’s rebels’ (Qatar, 14 January 2014) <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2014/1/14/isil-recaptures-raqqa-from-syrias-rebels> accessed 19 August 2023.

[32] Rosenblatt and Kilcullen, p.33.

[33] Reuter, Der Spiegel.

[34] RAND, ‘Raqqah: Capital of the Caliphate’ (n.d.) <https://www.rand.org/nsrd/projects/when-isil-comes-to-town/case-studies/raqqah.html> accessed 19 August 2023.

[35] Ibid.

[36] Interviews with Raqqa residents, April and May 2023.

[37] Al-Hakkar, Al-Akhbar English.

[38] Reuter, Der Spiegel.

[39] BBC, ‘Syria conflict: Isis “overruns” Raqqa military base’ (London, 25 July 2014) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-28481283> accessed 19 August 2023.

[40] Middle East Eye, ‘85 Syria troops reportedly killed in IS advance’ (London, 12 February 2015) <https://www.middleeasteye.net/news/85-syria-troops-reportedly-killed-advance> accessed 19 August 2023.

[41] Individual testimony #94.

[42] Individual testimony #66, focus group session 4.

[43] Jeffrey White, ‘Military Implications of the Syrian Regime’s Defeat in Raqqa’ (Washington Institute for Near East Policy, 27 August 2014) <https://www.washingtoninstitute.org/policy-analysis/military-implications-syrian-regimes-defeat-raqqa> accessed 19 August 2023.

[44] Individual testimony #164.

[45] Ibid.

[46] Individual testimony #123.

[47] Individual testimony #10.

[48] Ibid.

[49] BBC, ‘Jordan pilot hostage Moaz al-Kasasbeh “burned alive”’ (London, 3 February 2015) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-31121160> accessed 19 August 2023.

[50] Individual testimony #156.

[51] The exact number is unclear. Local officials from Raqqa’s municipality said more than 30 graves had been found, while the organisation Searching for Truth After ISIS refers to 28 mass graves and Human Rights Watch documented ‘more than 20 mass graves containing thousands of bodies’ across Syria.

See: Searching for Truth After ISIS, ‘After ISIS: Take urgent steps to find the disappeared’ (n.d.) <https://truthafterisis.org/en/>; Human Rights Watch (HRW) ‘Kidnapped by ISIS: Failure to Uncover the Fate of Syria’s Missing’ (11 February 2020) <https://www.hrw.org/report/2020/02/11/kidnapped-isis/failure-uncover-fate-syrias-missing> accessed 19 August 2023.

[52] The Arab Weekly, ‘Largest ever ISIS mass grave found near Syria’s Raqqa’ (21 February 2019) <https://thearabweekly.com/largest-ever-isis-mass-grave-found-near-syrias-raqqa> accessed 19 August 2023.

[53] Maya Gebeily, ‘Largest ISIS mass grave yet found outside Syria’s Raqqa’ Rudaw (21 February 2019) <https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/21022019> accessed 19 August 2023.

[54] Interviews with civil recovery personnel in Raqqa, April and May 2023.

[55] Syrian Observatory for Human Rights (SOHR), ‘Al-Raqqah mass grave: many bodies recovered and believed to be of “17th Division” members executed by ISIS’ (16 April 2020) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/160420/> accessed 19 August 2023.

[56] HRW, ‘Kidnapped by ISIS’.

[57] UNAMI/OHCHR, ‘Unearthing Atrocities: Mass Graves in territory formerly controlled by ISIL’ (6 November 2018) <https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/Documents/Countries/IQ/UNAMI_Report_on_Mass_Graves4Nov2018_EN.pdf> accessed 19 August 2023.

[58] HRW, ‘Into the Abyss: The al-Hota Mass Grave in Northern Syria’ 4 May 2020 <https://www.hrw.org/news/2020/05/04/abyss#_ftn10> accessed 19 August 2023.

[59] Ibid.

[60] Ibid.

[61] Interviews in Raqqa, April and May 2023.

[62] Individual testimony #4.

[63] Individual testimony #162.

[64] Individual testimony #169.

[65] Syria Justice and Accountability Centre, Unearthing Hope: The Search for the Missing Victims of ISIS (April 2022) p.29. <https://syriaaccountability.org/content/files/2022/04/ISIS-Missing-Persons-Report—Syria-Justice-and-Accountability-Centre—C.pdf> accessed 19 August 2023.

[66] Ibid.

[67] Individual testimony #66, focus group session 4.

[68] Individual testimony #69.

[69] Individual testimony #169.

[70] Individual testimony #52, focus group session 4.

[71] United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), ‘9th Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’ A/HRC/28/69 (5 February 2015), para.171.

[72] Saad Abedine and Jethro Mullen, ‘Islamists in Syrian city offer Christians safety – at a heavy price’ CNN (28 February 2014) <https://edition.cnn.com/2014/02/28/world/meast/syria-raqqa-isis-christians/> accessed 19 August 2023.

[73] Al-Hakkar, Al-Akhbar English.

[74] Ben Hubbard, ‘Disappearance of Activist Priest in Syria Stirs Fears He Is Dead’ The New York Times (New York City, 14 August 2013) <https://www.nytimes.com/2013/08/15/world/middleeast/activist-priest-in-syria.html> accessed 19 August 2023.

[75] Anthony Loyd, ‘Fall of Raqqa sheds light on disappearance of Father Paolo Dall’Oglio’ The Times (London, 29 December 2018) <https://www.thetimes.co.uk/article/fall-of-raqqa-sheds-light-on-disappearance-of-father-paolo-dall-oglio-2ldfskqvb> accessed 19 August 2023.

[76] Al-Hakkar, Al-Akhbar English.

[77] Employee of The New York Times & Ben Hubbard, ‘Life in a Jihadist Capital: Order With a Darker Side’ The New York Times (New York City, 23 July 2014) <https://www.nytimes.com/2014/07/24/world/middleeast/islamic-state-controls-raqqa-syria.html> accessed 19 August 2023.

[78] Alison Tahmizian Meuse, ‘In Show of Supremacy, Syria al-Qaida Branch Torches Church’ Syria Deeply (30 October 2013) <https://deeply.thenewhumanitarian.org/syria/articles/2013/10/30/in-show-of-supremacy-syria-al-qaida-branch-torches-church> accessed 19 August 2023.

[79] Stoyan Zaimov, ‘23 Christian Families Trapped in ISIS Stronghold Raqqa Facing Violence, Forced Taxes’ The Christian Post (17 November 2014) <https://www.christianpost.com/news/23-christian-families-trapped-in-isis-stronghold-raqqa-facing-violence-forced-taxes-129809/> accessed 19 August 2023.

[80] UNHRC, ‘Rule of Terror: Living under ISIS in Syria’ A/HRC/27/CRP.3 (14 November 2014), para.29 <https://www.ohchr.org/sites/default/files/documents/hrbodies/hrcouncil/coisyria/HRC_CRP_ISIS_14Nov2014.pdf> accessed 19 August 2023.

[81] Ibid., para.28.

[82] Individual testimony #9.

[83] Individual testimony #13.

[84] Individual testimony #127.

[85] Individual testimony #27.

[86] UNHRC, ‘Rule of Terror’, para.29.

[87] Individual testimony #35.

[88] UNHRC, ‘Rule of Terror’, para.52.

[89] Individual testimony #150.

[90] Individual testimony #9.

[91] UNHRC, ‘Rule of Terror’, para.51.

[92] Individual testimony #145.

[93] Individual testimony #97, focus group session 8.

[94] UNHRC, ‘Rule of Terror’, para.60.

[95] Individual testimony #50, focus group session 4.

[96] UNHRC, ‘Rule of Terror’, para.60.

[97] Amnesty International, Legacy of Terror: The Plight of Yezidi Child Survivors of ISIS (2020) <https://www.amnesty.org/en/documents/mde14/2759/2020/en/> accessed 19 August 2023.

[98] Al Jazeera English, ‘Syrian rebels announce offensive to retake Raqqa’ (Qatar, 6 November 2016) <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2016/11/6/syrian-rebels-announce-offensive-to-retake-raqqa> accessed 19 August 2023.

[99] Tom Perry, ‘U.S.-backed Syrian militias will close in on Raqqa: spokesman’ Reuters (6 March 2017) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-raqqa-idUSKBN16D0YE> accessed 19 August 2023.

[100] Rodi Said and Tom Perry, ‘U.S.-backed force launches assault on Islamic State’s “capital” in Syria’ Reuters (6 June 2017) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-raqqa-idUSKBN18X0LH> accessed 28 September 2023.

[101] Rudaw, ‘SDF enter east Raqqa in “Great Battle” for ISIS stronghold’ (6 June 2017) <https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/060620171> accessed 19 August 2023.

[102] SOHR, ‘On the 100th day of the grand battle of Al-Raqqah…SDF control more than two thirds of Al-Raqqah city’ (14 September 2017) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/74223/> accessed 19 August 2023.

[103] Quentin Sommerville and Riam Dalati, ‘The city fit for no-one: Inside the ruined “capital” of the Islamic State group’ BBC (London, 27 September 2017) <https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/resources/idt-sh/the_city_fit_for_no_one_raqqa_syria_islamic_state_group> accessed 19 August 2023.

[104] Individual testimony #79.

[105] Damien Gayle, ‘Last Isis fighters in Raqqa broker deal to leave Syrian city – local official’ The Guardian (London, 14 October 2017) <https://www.theguardian.com/world/2017/oct/14/last-isis-fighters-in-raqqa-seek-deal-to-leave-former-capital-in-syria> accessed 19 August 2023.