Before the Syrian conflict, Tabqa’s residents lived in relatively stable conditions compared with other areas of northeast Syria. However, years of uprising and war, followed by four years of ISIS rule between 2014 and 2017, left deep scars.

In many ways, Tabqa’s ordeal is not over.

Tabqa before the conflict

The district of Tabqa is located on the eastern bank of the Euphrates River. Built on a rocky hill overlooking the 80-kilometre-long Euphrates Lake (also known as Lake Assad), Tabqa is located immediately south of the 60-meter-tall Tabqa or al-Thawrah Dam. Administratively, the district is part of Raqqa province. Around 55 kilometres to the east lies Raqqa city, while 188 kilometres to the west lies Aleppo.

Tabqa had nearly 70,000 inhabitants before the conflict, according to Syria’s 2004 population census.[1] However, by 2021, the population had grown to 131,500 people, driven by wartime displacements from other parts of the country.[2] Tabqa’s largest community was Sunni Arabs, although alongside them lived diverse groups of Armenians, Kurds, roughly a thousand Assyrians, and Ismailis. There were also Alawi, Druze, Circassian, Chechens, Palestinians, Iraqi and even some German residents.

The city was known as al-Thawrah, or “the revolution,” a name commemorating the coup d’état (known as the 8 March Revolution) that brought the Ba’ath Party to power in Syria in 1963. Following the coup, much of Syria’s industrial and commercial infrastructure was nationalised, and the new regime pursued land reform.[3] These policies quickly diminished the economic power of the old bourgeoise and created a disparity between merchants, who fared well, and industrialists, who were heavily impacted as key industries were brought under the control of the government and a new state elite closely tied to the Ba’ath Party.[4] The influx of petrodollars and foreign aid made significant development programmes possible.[5]

One of the major development projects pursued by the Ba’ath regime was based in Tabqa: the city was chosen as a home for the $340 million Euphrates dam, known as the Tabqa or al-Thawrah Dam, constructed between 1968 and 1973 with the help of the Soviet Union (although the power station for the dam was not finalised until 1978).[6] The dam is one of the largest sources of electricity in Syria, with eight turbines generating about 824 megawatts; it is also a major source of drinking water for cities as far afield as Aleppo, and irrigates around a million hectares of agricultural land around the dam while protecting villages on its fringes from spring floods. During the decades before the Syrian conflict, Tabqa underwent major urban development projects to improve its roads, electricity, water and sewage infrastructure. The city also benefitted from a national hospital and other healthcare centres, which served the population free of charge. The city had a prominent cultural centre and was also home to an important local archaeological site, the castle at Jabaar.

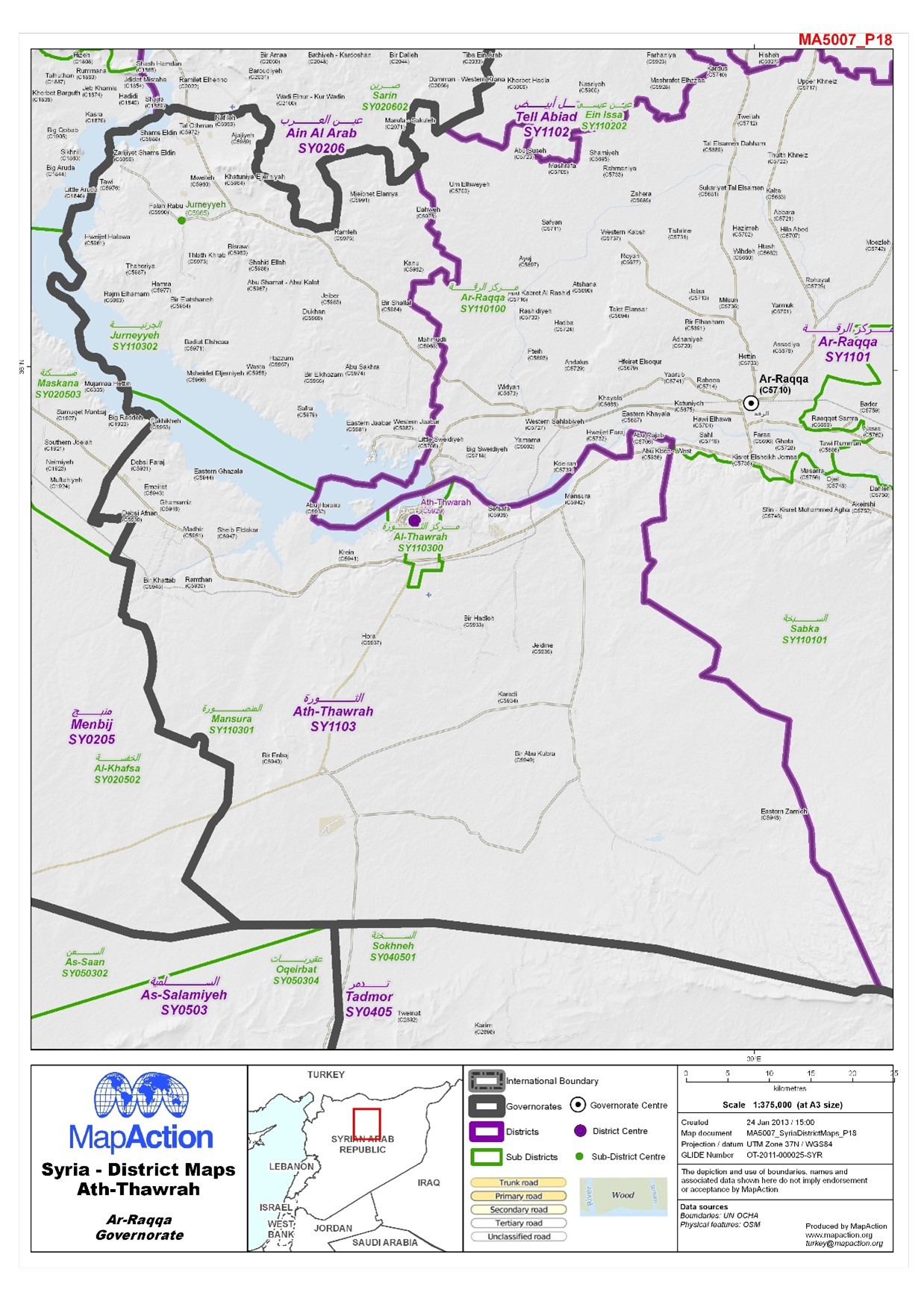

Figure 4: Al-Thawrah district within Syria’s Raqqa province.[7]

Construction of the Tabqa Dam significantly expanded and modernised the city of Tabqa. Many of Tabqa’s residents had originally migrated from other areas of the country to work on the dam, living in a northern section of the city in a lively, ethnically mixed area with bakeries, shops and restaurants known as “the Neighbourhoods” that lies adjacent to the Euphrates and Lake Assad. A distinguishing feature of this section of Tabqa, which set the city apart from other Syrian cities, was its urban planning, which had been carried out by Russian experts. Lush green vegetation surrounded the city’s concrete homes and houses.

The southern part of the city was separated from the Neighbourhoods by the railway, which was built to transport materials and supplies required for the construction of the dam. This part is the original village of Tabqa, which grew out of a small, unplanned agricultural village on the bank of the Euphrates. Tabqa had farming centres for fish, poultry and agricultural land irrigated from the Euphrates where cotton, barley, wheat, sugar cane and vegetables were grown. The government also provided tools for agricultural production. The public sector also served as a significant employer in the city.

To most people, life in Tabqa was pleasant. Sharing a widely held sentiment about life in the city before 2011, one interviewee said:

Before the crisis in Syria, we lived well. We had a lot of olive trees, farmland and cars. I had a taxi with my brothers. I was an employee at the Euphrates dam. The education levels in the city were very good. Women were free to wear anything and work in any role. The health sector was good, and services were free, affordable and available. There was a good hospital in the city.[8]

Another added:

Before 2010-2011, the situation [in Tabqa] was good. An employee’s monthly wage was around $200-$300. Health services were easily accessible and good. Many people used to go to government hospitals, not private hospitals. Everything was cheap, everything was good and available, and everyone liked to help each other and host each other.

However, the interviewee added grimly, “these things do not exist anymore.”[9]

The conflict in Tabqa

Because of the generally positive living conditions and high level of service provision in Tabqa, most of the city’s inhabitants were generally considered loyal to the Syrian regime in the pre-war period. But even so, the city was not immune to the security infiltration and inequalities that existed everywhere in the country.

Given the city’s strategic and economic importance, the Syrian government was convinced that Tabqa’s political, administrative and economic leaders should demonstrate their political reliability, if not absolute loyalty to the regime. While a handful of left-wing political parties—namely the Syrian Communist Party and parties of the National Progressive Front—were permitted to engage in politics alongside the ruling Ba’ath Party, key political and economic departments were controlled by members of the Ba’ath Party and the security services. This included the General Authority of the Tabqa Dam as well as the al-Thawrah oilfield, where administrative staff earned higher wages and enjoyed additional benefits. Many people originally from the surrounding area were deprived of the kind of prestigious jobs in strategic industrial departments offered to those migrating in from elsewhere.

This meant that once demonstrations erupted across Syria after 18 March 2011, some people in Tabqa participated while others did not. The central government responded to the popular protests with arbitrary arrests and enforced disappearances targeting local residents while increasing the presence of the security and intelligence services in local communities. The brutality of the security services created a vicious, escalating cycle of protests met with repression that led to funeral marches and larger protests, and it did not take long for armed opposition factions to appear in the district amid the instability that followed.

In late 2012, armed opposition groups took control of the Tabqa Dam,[10] and by the beginning of 2013 wrested control of Tabqa itself from the Syrian government.[11] The coalition of opposition factions that controlled Tabqa included Jabhat al-Nusra, Ahrar al-Sham, and a number of smaller battalions. While many of these promoted themselves using revolutionary slogans and offers to protect local communities, it became readily apparent that their ideological objectives were to establish an Islamic state in line with Islamist interpretations of Shari’a law. Throughout 2013, intense clashes between pro-Assad and opposition took place in and around the city and near dam. Syrian Air Force (SAF) warplanes conducted repeated airstrikes and aerial raids from the nearby Tabqa Military Airport to the city’s southeast.[12]

The arrival of ISIS

When tensions between Nusra leader Abu Muhammad al-Jolani and then-leader of ISI, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi, broke out into an all-out schism and Baghdadi announced the existence of ISIS, Nusra fighters stationed in Tabqa split into two camps. Abu Issa, Nusra’s commander in Tabqa, pledged allegiance to Jolani along with many local members of the group; others, including the so-called “migrants” of Nusra who were not from Tabqa, opted to join ISIS.[13] This sparked fighting between the two sides, and armed opposition groups joined forces with Nusra against ISIS. A short but vicious fight for the city ensued, in which ISIS made extensive use of car bombs and suicide bombers. The battles soon went in ISIS’ favour and in early 2014, the group took control over most of the local area, including al-Mansoura to the east as well as Tabqa city and its surrounding rural areas.[14]

By late June 2014, when ISIS declared its so-called “caliphate” with Baghdadi at its head, the group divided territory under its control into wilayat (provinces). Located close to the group’s self-proclaimed capital in Raqqa, Tabqa was called “Sector West” and assigned its own provincial ruler, Awwad al-Khalifa (otherwise known as Abu Hamza).[15] Under his rule, ISIS members forced local residents to pledge their allegiance to the “caliphate” and the “caliph” during Friday prayers in Tabqa and surrounding areas; tribal leaders were also forced to pledge allegiance. Those who refused knew their fate beforehand.

In August 2014, ISIS began preparations to capture Tabqa Military Airport. The group had already brutally captured Syrian army bases for the 17th Division in Raqqa and 93rd Brigade in rural Raqqa’s Ain Issa, killing captive soldiers and beheading their corpses.[16] Led by Abu Omar al-Shishani, an Uzbek national and ISIS’ so-called “minister of war,” ISIS aimed to besiege the airport from all directions except the south, giving Syrian troops a corridor through which they could flee.[17]

The battle began on 10 August 2014. Initial attacks by ISIS were unsuccessful, and SAF planes launched retaliatory and largely indiscriminate strikes on Raqqa and Deir Ezzor that caused significant civilian casualties in both cities. Fighting continued for over two weeks. But after bringing in military reinforcements, hundreds of ISIS fighters finally stormed the airport after a double suicide bombing targeted the airbase’s entrance, seizing the base on 24 August. Observers estimated 346 ISIS fighters and more than 170 army troops died in the battle for the airport.[18]

Once inside the airport, ISIS fighters killed more than 200 Syrian soldiers in a massacre. A UN report said the men ‘were stripped to their underwear and forced to walk into the desert’ while a video later broadcast by ISIS ‘showed hundreds of bodies lying dead in the sand, bearing gunshot wounds to the head.’[19] Many others fled and were chased down, with an estimated 300 soldiers captured and subsequently executed by beheading in Tabqa or other ISIS-held areas. After broadcasting a video of the massacre, one of the largest perpetrated by ISIS in terms of single casualties, ISIS dug a mass grave for the bodies of approximately 500 soldiers. Interviewees recounted seeing children playing with soldiers’ severed heads in the streets shortly afterwards.[20]

‘No one knew wha they did with his body’: Torture and executions in Tabqa

Once ISIS had taken full control of Tabqa district, a new phase of terror began, defined by killings in the street and public executions and qasas (retribution) punishments.

Not long after capturing Tabqa airbase, ISIS members brought people whom they accused of apostasy to Tabqa’s main market roundabout. On the basis of family testimonies and video evidence, the research team was able to ascertain that they gathered most of the city’s inhabitants to demonstrate what would happen to those who violated ISIS’ teachings. ISIS members forced captives onto their knees, with a masked ISIS member standing behind each one of them. After the order was given by the emir of the group, they shot them execution-style from behind. Blood ran down the streets.

Another massacre was committed by ISIS on 16 November 2014, when the group killed 13 people from the village of al-Safsaf following afternoon prayers.

The mother of a victim recounted the story of her son, who was killed in a mass execution during this period:

Six months after they were detained, ISIS members sentenced my son and seven other people. They were from various clans, mostly the Bu Khamis clan. The signs of torture were visible on their bodies.

The day of the qasas was Saturday, at 10 am. [It was done] in front of the local people. They shot them dead […] and then left them hanging outside as an example for others. [ISIS] killed people to sow fear and panic inside us.[21]

People were killed on charges of being regime agents: following the capture of Tabqa’s airbase, ISIS began a campaign of arrests inside the city and outlying countryside on the grounds that they had found documents at the airport naming regime agents operating within the city. Similarly, in 2016, ISIS killed a number of civilians in Tabqa, claiming they were operating as Turkish agents.

Others were killed on charges of atheism and disbelief. According to information gathered for this report, at least 800 residents of Tabqa were killed by ISIS members on sentences issued by the group’s so-called Shari’a Court. Often, however, sentences were handed down without even a semblance of court intervention or due process. Those marked for execution were placed in a prison with a security tower, which was known to the people of Tabqa as the “Death Prison.”

A woman described how her father was killed:

We didn’t know where our father was for more than 40 days. We later found out that he’d been sentenced to “retribution,” but we didn’t know where or when. Then, we found out from eyewitnesses that his death sentence had been carried out and my father was heard saying that he was innocent. He was beheaded, and then wrapped in a cover. No one knew what they did with his body.

Two months later, security personnel came to confiscate my father’s house and property. They forced us out and locked the house with iron chains.[22]

Another woman shared the story of her son, M., who was detained after getting into a fight with a foreign ISIS fighter. As she and her other son, Y., were walking home, a car filled with ISIS members stopped next to them. She was “so afraid of them,” the woman remembered, that she rushed to get home unharmed. Only later would she learn that M. was actually in the car because he had wanted to see his mother and brother one last time. Shortly afterwards, he was executed in horrific fashion:

I felt something had happened to my son, so I asked his little brother to go to the qasas courtyard [to] ask people who was going to be executed, and to come back and tell me.

My son did not go, and I got busy with the housework. [Then an] ISIS member, [who] I saw in prison, came and asked me to get into the house. They wanted to talk to my little boy [Y.].

ISIS members told him that the qasas sentence had been applied to [M.]. My son came and told me. I could not hold myself together. I was crying. I told them I wanted to see him.

They said: “Come with us.” It was so they could hand me his body. I was not in a state where I could absorb and understand. So, I came out and I understood from them that they threw him from a high building, from the fifth floor. He did not die straight away so they stoned him to death… by hitting his head with stones.[23]

Dead bodies were regularly strung up or crucified, and people, including family members, were forbidden from approaching them. Some had their heads cut off with swords, which would be hung separately from the body. ISIS members encouraged children to approach the dead bodies and beat them with shoes; they also handed children pistols to aim at the bodies and shoot them. Executions were often filmed and posted on ISIS’ social media channels. They called these videos “versions,” which were copied onto hard drives and displayed on large screens in public squares. This served two purposes—to intimidate the population, but also to drive recruitment.

To ISIS fighters, executions were often a righteous act of religious cleansing. In some, they instilled joy and happiness. One victim witnessed this after his relatives were executed, learning the tragic news from a prison cell where he was being held by ISIS:

After nearly three hours, around one o’clock, ISIS members came to the al-Burj Prison. They were joyous and delighted, as if they’d just won a great victory. Someone entered and started addressing my brother. He told him that the [death] sentence had been applied to his children. In his words, the “apostate infidelity” was finished.

His speech had the effect of a thunderstorm on us. We thought they wanted to scare us, their faces were smiling and joyous.

At one o’clock after midnight, a Saudi [fighter] came to the cell, I don’t know his name, and said: “Come with me.”

When I came out with him, he started playing a video on his mobile phone showing the moment they [executed] my nephews and the others with him. There were thirteen people [killed] in the main market square of Tabqa [with my nephew].[24]

Being accused of a crime, no matter how spurious the accusations, could have devastating consequences. Hypocrisy was rampant too, and often ISIS fighters used accusations to deflect attention from their own actions that ran against the group’s interpretation of Shari’a. One victim from Tabqa recounted how his brother was killed by ISIS for selling cigarettes to the mother of an ISIS member.[25] In another case in al-Mansoura from 2015, ISIS’ hisba police executed eight people on charges of theft after one of the men borrowed money from a creditor, who was close to ISIS’ security apparatus in Tabqa, and failed to pay the amount back in time. Following a complaint from the creditor, ISIS arrested the man and seven others, executing them all on the same day and displaying their bodies in the street for hours as a warning to others.

In other cases, ISIS resorted to specific punishments for specific crimes. The standard punishment for theft, for example, was to cut off one hand of the accused. A mother who lost one child to ISIS recounted how her other son, 15 years’ old at the time, lost his hand in this way:

My second son [A.] had his right hand cut off by ISIS for theft. One day between 2015 and 2016, he and his cousin were playing football. The ball fell into the house of an Uzbek member of ISIS. My nephew climbed the wall and went into the house without their permission. My son didn’t climb the wall, he [helped] his cousin to enter the house. ISIS members grabbed them and accused them of theft. [They] applied the sentence of cutting off his right hand.[26]

Another victim, who himself lost a hand to ISIS’ brutal penal system, talked about his psychological condition because of what he went through: “After ISIS cut off my hand, I suffered a serious psychological illness. I was unable to work or leave the house. I was afraid of what people would think, and because it would remind me of the incident.”[27]

‘They had no dignity’: Violations against women and girls

ISIS’ treatment of women and girls, who were forced to cover their bodies and limit their freedom of movement, was just as stringent in Tabqa as in other areas of northeast Syria. One woman recounted how:

My neighbour was an old lady, they beat her in the market in front of everyone because she did not cover her eyes. A [male] member of the hisba asked her why she hadn’t covered her eyes. She replied: “Why are you looking at my eyes?” Then he beat her in front of everyone.[28]

As well as patrolling the streets, female hisba units could also implement sentences including fines, prison terms, or corporal punishments such as flogging, and death sentences such as stoning. At least two women were stoned to death in Tabqa city, one near the al-Furqan Mosque and the other by the city’s microbus station. One of the victims was Shamseh Abdullah, who was killed on 18 July 2014.[29] Hisba members would forcefully gather people from the streets and the mosques an hour before the execution of the sentences to attend the executions. The order would then be given to throw stones until the woman had died, although according to reports, residents of Tabqa refused to take part and the act was carried out by ISIS members instead.[30]

The research team also spoke with the sister of one of the women from Tabqa who was publicly stoned to death. She recounted how her sister, who was accused of prostitution, had called her the day before her death and told her that ISIS had set the time for her stoning. She had asked her sister, “Pray for me, all of you, for mercy and forgiveness, and tell my mother to forgive me and pray for me.”[31] The next day, she was killed.

As in other areas, captive women known as sabaya—most of whom were Yazidi women and girls from Iraq’s Sinjar region—were sold on slave markets in Tabqa. One woman from Tabqa described how her husband, whom she herself had been forced to marry, brought home a sabaya:

ISIS […] brought us back to ancient times. The treatment of sabaya had nothing to do with humanity. They had no dignity.

[Women and girls] were raped and sold in markets or through private groups on Telegram. They worked as maids for ISIS women and men. They were introduced to men’s gatherings to serve them, despite the prohibition of mixing without wearing a hijab or Shari’a dress.

My husband, who was an ISIS member, brought me a sabaya: her name was Sarah. She was 13. He got her as a gift. Then he, in turn, gifted her to me. I was confused about whether to treat her like a child or sabaya. I treated her like my child. She converted to Islam because of me. I set her free after she became Muslim and got married at the age of 14.[32]

Other women were forcibly married. They, too, were often subjected to severe sexual abuse. One victim from Tabqa told us how she was forced to marry a British ISIS fighter. He subjected her to physical and sexual violence, including while she was pregnant:

My second pregnancy was with my daughter, [S.]. Because of the severity of [my husband’s] beatings on my abdomen while I was pregnant, [S.] had a fracture in her head while she was in my womb. Two hours after she was born, she died of a head fracture. Her head was split into two.[33]

‘Are my hands still there?’: Forced disappearance, arbitrary detention and torture

As part of its broader system of detention facilities, ISIS created dozens of secret prisons and torture centres in the surrounding area, including al-Burj Prison in Tabqa city, al-Sadd Prison in the Tabqa Dam complex, the Stadium Prison in Raqqa, and Point 11, which was considered ISIS’ “death and execution” prison in Raqqa.

One victim subjected to torture remembered how:

They brought me into the torture room. I was tied up and my hands were raised behind my back. This method was called “suspension,” one of the most horrendous types of torture, which caused me so much pain. I was able to resist for about an hour and a half, and then I fainted. At the time of the al-Maghrib [evening call to] prayers, they brought me down. The same day, I was taken to the dormitory. I couldn’t feel my hands. I remember asking someone: “Are my hands still there?” They told me they were.

After the al-Maghrib prayers, I was called in for investigation again. I was blindfolded and handcuffed. I felt the presence of other people [detained in the room with me]. The investigator asked his officers to cover their faces with masks and ordered them to load their weapons, which made me have an unspeakable breakdown out of fear. But there was no shooting. More than two minutes of terrifying silence and severe panic passed.

The official then ordered us to take off our blindfolds. However, I couldn’t take mine off because […] I couldn’t move my hands from the torture. I couldn’t even feel my hands.

He asked me: “Why didn’t you take [off] your blindfold?”

I replied: “I can’t move my hands.”

So, he ordered someone […] to take the blindfold off my eyes. I was surprised to see that the people who had been detained with me in the room were my two brothers and my nephew.[34]

Other victims reported being tortured by suspension, with some being left hanging from the ceiling for six consecutive days.[35] They also suffered dulab beatings, an infamous torture method in Syria by which a prisoner is forced inside a vehicle tire and then beaten. Another victim described their torture inside an ISIS detention facility:

They beat me on the feet. Then, I was led to solitary confinement. They forced me into the squatting position for a long time, causing numbness in the whole of my body. An ISIS member then came and took me to the torture room, handcuffed my body to a wooden chair and beat me until I couldn’t move anymore.

I screamed out: “I seek refuge with Prophet Muhammad [Peace Be Upon Him].”

They told me: “You have called someone besides Allah by saying this and you must be executed—even if you were innocent of the charge for which you were detained.”

I wished I was dead. In the evening, I was taken to [be] torture[d], but this time by a different method. They brought me into a room with a small screen to watch [videos] of people being killed and tortured.

They had other harsh methods. I remember they handcuffed me to the prison wall standing up, and then somebody attached a piece of iron weighing about 2 kilos to my genitals. I lost consciousness. This process was repeated more than once. This is what caused my sexual dysfunction [that I suffer from] until now.

After I was beaten, they moved me to solitary confinement because I couldn’t stand on my feet. The jailor asked me to stay in the squatting position. There was a camera recording my movements in the room. He threatened me, saying if I moved and changed the way [I was sitting], then he would take me back to the torture room.[36]

Violations against Tabqa’s minorities

ISIS destroyed Tabqa’s pre-war mosaic of ethnic communities. Some fled the indiscriminate shelling and car bombs that ISIS deployed in residential areas during its military advances, or the public executions and torture it employed after subjugating an area. However, many of Tabqa’s minorities were forced to migrate later under the threat of arms or because their property was confiscated. Others were made to convert to Islam or forced to pay the jizyah tax in return for their “protection.” One resident of rural Tabqa remembered:

ISIS confiscated agricultural land. They forced us to pay tributes for farmland. You had to convert your money into dirhams and dinars to pay the taxes they imposed on you.

My neighbour was Christian, they fined her a large annual tribute of 25 grams of gold—so that she could keep her home, stay in the area and remain Christian [without having to convert to Islam]. She had to pay [that amount] ever year.[37]

Among those affected were Tabqa’s Christians and Assyrians, who until the start of the conflict, practiced at their own churches in the area. Alawis, Kurds and Shi’a, who had previously lived side by side with Sunni Muslims, were also subject to pressure and intimidation. At least 600 Christian families from Tabqa city alone were displaced as part of ISIS’ exclusionary and sectarian policies. ISIS pitted tribes and ethnic groups against each other and sowed discord and intra-community conflicts.

All in all, the city was transformed into “one big detention centre,” according to those who lived through ISIS rule. The group established various government departments in Tabqa that were connected to ISIS’ overarching governance structures. This included offices for taxation, education, recruitment, religious outreach and mosques. ISIS prohibited people from watching TV and satellite channels, and anyone who did not hand over satellite receivers would be punished with the most severe penalties and fines. Infrastructure was destroyed and exploited by ISIS to serve its agenda. The local economy suffered from the confiscation of people’s property, homes and livelihoods, the closure of small enterprises, taxation and royalties such as zakat (taxation).

One victim described how their lives changed after ISIS’ takeover of Tabqa:

The economy deteriorated. Travel was prohibited and impossible. If you decided to travel, you’d be exposed to all kinds of risks. You’d be exposed to gangs and bandits, on top of your fear that ISIS would catch you.

Education deteriorated. We did not send our children to schools opened by ISIS for fear of bombing or due to the curriculum taught by ISIS, which promoted violence and hatred. Hospitals were only for [ISIS fighters], their women and their children.

Getting out of the house was not easy, either. You couldn’t walk with your wife without taking proof that she was your wife. Life was difficult. Many sold their land and property to [leave]. We no longer wanted to move out of our homes because of the fear and terror we experienced when we went out.[38]

ISIS-induced poverty had profound consequences. The population of Tabqa, often well-educated compared with other cities in northeast Syria, was forced to work with ISIS in both military or civilian capacities, either under direct threat of violence or because they were compelled to do so out of pure economic reality. A woman from Tabqa said:

I was a worker, I used to get a salary, but then I got suspended. Women in the time of ISIS could not go out. Life was hard.

One day, my daughter passed through four rooftop houses to escape ISIS. When they caught her, they took my husband and son and imprisoned them all. They forced them to attend a [repentance] course and whipped them. We had to pay for the Shari’a dress for our daughters, even if we couldn’t afford it.[39]

The educational system suffered too. People said that schools were “stolen” and children dropped out. One interviewee reported that his brother, an ISIS member, forced their sister to drop out of school: she remains illiterate today.[40]

Tabqa’s children suffered under the repressive regime imposed upon them. ISIS turned schools in Tabqa into military complexes, some with tunnels running beneath them.[41] It targeted children with extremist propaganda, raising the next generation on violence and extremism. Residents interviewed said ISIS contributed to illiteracy or prevented people from completing their education. A mother described how this had affected her son:

One day, my son was watching execution videos. He was five years’ old. He was holding a knife and wanted to try to slaughter his brother, who was just a few months’ old. I entered the room at the right time, saw this incident, and I managed to protect my little boy.[42]

Children were recruited and placed in camps called “Cubs of the Caliphate,” where they were taught about violence. Some children reportedly took part in the field executions that ISIS carried out after taking control of Tabqa airport. ISIS’ recordings of the executions, reviewed by the research team, showed children standing behind prisoners with pistols, and killing them when given the order. Allegedly, some children were as young as six years of age while participating in this violence. Other children in Tabqa were forced to grow up without parents, leaving family members scrambling to take care of them:

I have five orphaned children; they are my nephews. Their parents were executed by ISIS. My parents are sick. I have two children with disabilities, my sister is blind. I am a daily worker and I have nothing. I had been dismissed from my work at the Tabqa Dam. Two orphans were sent to an orphanage in Aleppo.[43]

People interviewed described how the trauma inflicted upon children had made them into “ticking bombs.” Another common refrain was that “this generation does not care about anything” or believe in anything larger. Children who grew up in Tabqa, once a peaceful town, under ISIS rule have grown up disillusioned and deprived of their childhood.

The liberation of Tabqa

ISIS controlled Tabqa for nearly four years. Efforts to liberate the city gathered steam in the autumn of 2015. Following their campaigns to seize Kobane and large swathes of Hasakeh province, the YPG and YPJ, together with several Arab, Syrian, Armenian and Turkmen battalions, announced the formation of the SDF in late 2015.[44] In 2016, the SDF, with air support from the US-led Coalition, liberated Manbij, which borders Tabqa district. The following year, the SDF launched a campaign to liberate Tabqa, calling it “Operation Wrath of the Euphrates.”[45]

ISIS fighters had holed up inside the Tabqa Dam and opened three turbines, flooding areas downstream.[46] The UN warned that deliberate sabotage by ISIS or US airstrikes, which had already damaged the entrance to the dam, could lead to catastrophic flooding of surrounding areas.[47] In March 2017, US special forces and SDF fighters were airdropped into the al-Karin area, behind enemy lines, to begin a ground assault.[48] As the SDF captured various villages in the area, ISIS forces withdrew with the SDF in pursuit. Civilians who were unable to leave were used as human shields by ISIS, with the group decreeing that each person leaving the area would be regarded as an apostate and infidel and would be executed on sight. ISIS also planted anti-personnel mines in the area, which continue to plague the area today.

By 24 March, the SDF had reached the entrance of the dam, and heavy battles ensued. Despite being on a “no-strike” list, US warplanes dropped three 2,000-pound bombs on the dam, leading the dam to stop functioning and the reservoir to rise more than 15 metres, nearly causing a catastrophic spill-over.[49] ISIS, the Syrian government, the SDF and the US then agreed on an emergency ceasefire to avert disaster.[50] A day later, the SDF said the dam was ‘not damaged or malfunctioning.’[51] The SDF seized the majority of Tabqa’s airbase, which it soon brought under its full control.[52]

With ISIS surrounded and its supply routes cut off, the battle for Tabqa city started on 15 April 2017. ISIS withdrew to the Neighbourhoods in northern Tabqa after sending several car bombs to stop the SDF’s advances. The SDF claimed that ISIS, surrounded and besieged, had threatened to blow up the dam.[53] To avoid this scenario, which risked killing tens of thousands of people, the SDF and ISIS negotiated a deal to open a corridor through which ISIS fighters could withdraw to Raqqa.[54]

On 10 May 2017, the city of Tabqa was declared liberated, although some battles continued in the ruins and orchards of al-Mansoura where ISIS had dug extensive tunnel networks. After intense battles and airstrikes by the US-led Coalition, a difficult negotiation was conducted through elders and clan leaders. Initially, ISIS resisted withdrawal in an attempt to appease its fighters. But besieged and increasingly isolated, ISIS was forced to accept withdrawal under guarantees from the negotiators and on the condition that fighters could leave with their individual weapons.

The aftermath

The offensive and ensuing evacuation deal eliminated ISIS’ last territorial foothold in Tabqa. The SDF subsequently conducted mine-clearing operations and over the next year, would establish local governing structures. Some of the displaced began to return and the daunting task of rubble clearance began. While life gradually returned to Tabqa, the legacy of four years of ISIS occupation lived on in the minds of people, leaving the city battered and its people scarred.

During data collection, the research team encountered noticeable signs of fear about the possible return of ISIS. Interviewees talked about their fears of being targeted by ISIS sleeper cells. As a result, many victims approached for interviews simply refused to discuss their experiences. Even those who did agree to speak took extreme precautions, speaking to researchers briefly, clearly in a hurry to end the interview. This trend was particularly pronounced in rural areas surrounding Tabqa city.

Despite these challenges, the people from Tabqa told their own—often harrowing—stories of public executions, physical and sexual violence against women and torture. Many suffered severe psychological trauma, especially children who grew up in a decade marked by war and violence. Tabqa’s suffering may have eased, but it has not ended.

Footnotes

[1] Syrian Central Bureau of Statistics, ‘Syria Population Census, 2004’ (Ar.) (n.d.) <https://web.archive.org/web/20151208115353/http://www.cbssyr.sy/General%20census/census%202004/pop-man.pdf> accessed 17 August 2023.

[2] Rojava Information Center, Beyond Rojava: North and East Syria’s Arab Regions (June 2021) <https://rojavainformationcenter.com/storage/2021/06/RIC-Dossier-Arab-regions.pdf> accessed 18 August 2023.

[3] Ziad Keilany, ‘Land Reform in Syria’ (1980) Middle Eastern Studies 16(3) <https://www.jstor.org/stable/4282794> accessed 18 August 2023.

[4] Volker Perthes, ‘The Bourgeoisie and the Baath: A look at Syria’s Upper Class’ (1991) MERIP 170 Middle East Report <https://merip.org/1991/05/the-bourgeoisie-and-the-baath/> accessed 18 August 2023.

[5] Volker Perthes, Staat und Gesellschaft in Syrien, 1970-1989 (Schriften des Deutschen Orient-Institutes, 1990), p.82.

[6] Many workers paid their lives as a price for its completion: an estimated 91 people died during the construction of the dam.

[7] Map Action, ‘Syria District Maps: Ath-Thawrah’ (4 July 2016) <https://maps.mapaction.org/dataset/217-2789/resource/c3b5fbb7-9a5f-4bff-a517-5d7e25502ee9> accessed 18 August 2023.

[8] Individual testimony #14, focus group session 1.

[9] Individual testimony #90, focus group session 3.

[10] Alison Tahmizian Meuse, ‘Syria rebels seize dam’ AAP (26 November 2012) <https://web.archive.org/web/20121129050853/http://www.perthnow.com.au/news/breaking-news/syria-battle-reaches-damascus-outskirts/story-e6frg13l-1226523898402> accessed 18 August 2023.

[11] BBC, ‘Rebels “take control of key north Syria airbase”’ (London, 11 January 2013) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-20984142> accessed 18 August 2023.

[12] Al-Bawaba, ‘Fierce Syria clashes on Lebanese border force government to launch tighter border policies’ (Amman, 21 November 2013) <https://www.albawaba.com/news/syria–535295> accessed 18 August 2023.

[13] Interviews with Tabqa residents, April and May 2023.

[14] Ibid.

[15] Ibid.

[16] United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), ‘9th Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’ A/HRC/28/69 (5 February 2015), Annex 2, para.22.

[17] Interviews with Tabqa residents, April and May 2023.

[18] Sylvia Westall, ‘Hundreds dead as Islamic State seizes Syrian air base: monitor’ Reuters (24 August 2014) <https://www.reuters.com/article/cnews-us-syria-crisis-idCAKBN0GO0C520140824> accessed 18 August 2023.

[19] UNHRC, ’9th report’, para.24.

[20] Interviews with Tabqa residents, April and May 2023.

[21] Individual testimony #49.

[22] Individual testimony #47.

[23] Individual testimony #37.

[24] Individual testimony #34.

[25] Individual testimony #48.

[26] Individual testimony #29.

[27] Individual testimony 56, focus group session 2.

[28] Individual testimony #29, focus group session 1.

[29] Al-Arabiya News, ‘Women stoned to death in Syria for adultery’ (9 August 2014) <https://english.alarabiya.net/perspective/features/2014/08/09/Women-stoned-to-death-in-Syria-for-adultery> accessed 18 August 2023.

[30] Ibid.

[31] Individual testimony #27.

[32] Individual testimony #29, focus group session 1.

[33] Individual testimony #41.

[34] Individual testimony #34.

[35] Individual testimony #35.

[36] Individual testimony #58.

[37] Individual testimony #48, focus group session 2.

[38] Ibid.

[39] Individual testimony #89, focus group session 3.

[40] Individual testimony #29, focus group session 1.

[41] Individual testimony #16, focus group session 1.

[42] Individual testimony #41, focus group session 2.

[43] Individual testimony #14, focus group session 1.

[44] Kurdish Question, ‘Declaration of Establishment by Democratic Syria Forces’ (15 October 2015) <https://web.archive.org/web/20160224085811/http://kurdishquestion.com/index.php/kurdistan/west-kurdistan/declaration-of-establishment-by-democratic-syria-forces/1179-declaration-of-establishment-by-democratic-syria-forces.html> accessed 18 August 2023.

[45] UNOCHA, ‘Syria Crisis: Ar-Raqqa—Situation Update No. 1 (as of 31 January 2017)’ (Reliefweb, 31 January 2017) <https://reliefweb.int/sites/reliefweb.int/files/resources/raqqa_update_dec-jan_2017_0.pdf> accessed 18 August 2023.

[46] Ibid.

[47] Tom Miles, ‘U.N. warns of catastrophic dam failure in Syria battle’ Reuters (15 February 2017) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-dam-idUSKBN15U1DZ> accessed 18 August 2023.

[48] Rudaw, ‘Coalition airdrops SDF and US forces into Tabqa for joint operation’ (22 March 2017) <https://www.rudaw.net/english/middleeast/syria/22032017> accessed 18 August 2023.

[49] Dave Phillips and others, ‘A Dam in Syria Was on a “No-Strike” List. The U.S. Bombed It Anyway’ The New York Times (New York City, 20 January 2022) <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/20/us/airstrike-us-isis-dam.html> accessed 18 August 2023.

[50] Ibid.

[51] Reuters, ‘Syria dam not damaged: SDF Raqqa campaign spokeswoman’ (27 March 2017) <https://www.reuters.com/article/idUSKBN16Y1JG> accessed 18 August 2023.

[52] Al Jazeera English, ‘US-backed Syria forces pause operations near Tabqa dam’ (Qatar, 27 March 2017) <https://www.aljazeera.com/news/2017/3/27/us-backed-syria-forces-pause-operations-near-tabqa-dam> accessed 18 August 2023.

[53] Rodi Said, ‘U.S.-backed assault on Raqqa to last months, commander says’ Reuters (31 March 2017) <https://www.reuters.com/article/mideast-crisis-syria-raqqa-idINKBN17218T> accessed 18 August 2023.

[54] SOHR, ‘18 days after entering the city… the Syria Democratic Forces almost completely control al-Tabaqa and ISIS withdraw after negotiations’ (3 May 2017) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/65729/> accessed 18 August 2023.