Located in the highly strategic triangle between the Syrian, Iraqi and Turkish borders and trisected by two rivers, the Khabour and Jaghjagh, Hasakeh would take on vital importance for the Syrian government, SDF and regional players during the anti-ISIS conflict.

Due to its natural resources, ISIS expended considerable effort to take control of Hasakeh. Home to the base of operations of the Kurdish-led resistance to ISIS in northeast Syria, Hasakeh was also an important military target for the group. This led to intense fighting between ISIS and Kurdish-led groups such as the YPG from 2014 onwards. Although ISIS was never able to obtain full control over the area, it still inflicted severe damage there.

Hasakeh before the conflict

Hasakeh province is located 600 kilometres east of Damascus and nearly 200 kilometres north of Deir Ezzor. It also borders Turkey and Iraq, which lie to its north and east, respectively.

At 23,334 square kilometres, the province’s territory is twice the size of Lebanon, and contains 1,717 villages. Hasakeh is rich in water, containing as much as 52% of Syria’s total water resources, and has historically been considered the “breadbasket” of Syria. Due to this abundance of water and agriculture, together with Raqqa and Deir Ezzor the region is also known as al-Jazeera, “the island.”

Hasakeh province is sub-divided into four districts.[1] Bordering Deir Ezzor, Hasakeh is the southernmost of the province’s four districts and contains the provincial capital that gives the district its name. Some attribute its name, which means “the thorn,” to the abundance of thorny vegetation in the area. Kurdish historians, however, attribute it to the name of one of the local Yazidi Kurdish clans, the Haskan clan, whose members used to live in the area extending from Iraq’s Sinjar to the Abdulaziz mountain range (known in Kurdish as the Kazwan Mountains). Hasakeh city is inhabited by Kurds, Arabs, Syriacs, Assyrians and Armenians. Important towns in the area include Tal Tamr, al-Hol, al-Shaddadah, al-Arisha, Merkada, Bir al-Helou. In addition, there are 595 villages in the district.

Qamishli, or Qamishlo in Kurdish (and Beit Zalin in Syriac), is considered by Kurds as their capital in Syria. The city is located on the border with Turkey and in the foothills of the Taurus Mountains, close to the Turkish city of Nusaybin. A modern city, established in 1925 by the authorities of the French Mandate, Qamishlo/Qamishli’s location was presumably chosen so that a French military base could be positioned at a strategic location straddling the Jaghjagh River and Aleppo-Nusaybin “Taurus” railway. Unlike other cities in the surrounding area, Qamishlo/Qamishli was planned with straight and parallel streets and well-organised city planning. It is locally known as “Little Paris.” Kurds and Syriacs were among the first to inhabit the city before the arrival of the Armenians and Arabs; today, these groups live alongside small minority communities such as Assyrians, Chaldeans, Mahlamis and Mardaliyya. Although the majority of the population is either Muslim or Christian, Qamishlo/Qamishli also has a small Jewish minority who previously immigrated from the US and Israel.

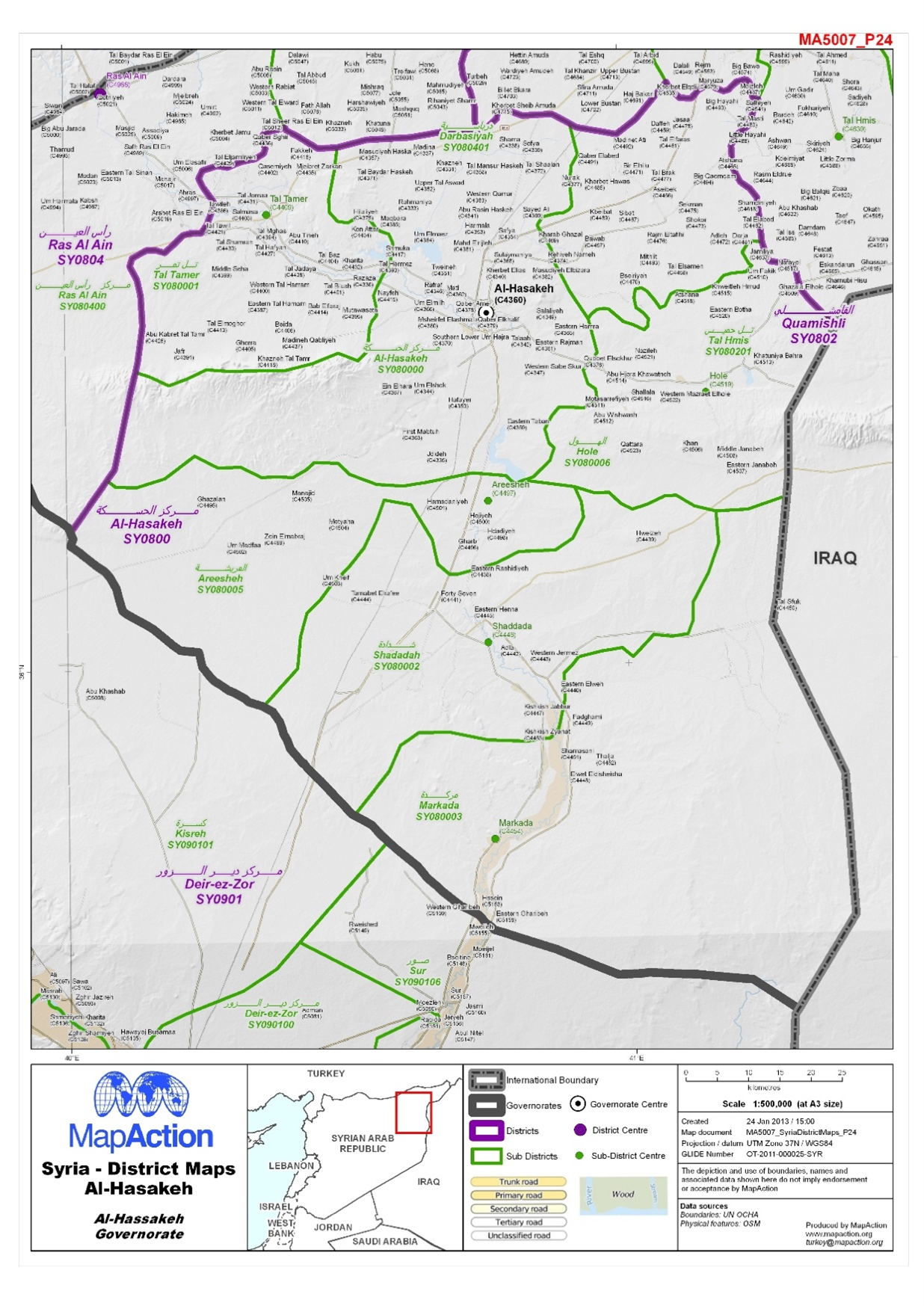

Figure 2: A map of Hasakeh district within Hasakeh province.[2]

Al-Malikiyah’s original name is Derek or Derik, derived from the Syriac word deroni, which means “small monastery”—a reference to the church previously located in the east of the original village. Derik/al-Malikiyah is located on the flat Hisnan Plain on the northeastern tip of the border triangle between Syria, Iraq and Turkey; the Tigris lies to the north, al-Radd to the south and Mount Judi to the east. It contains several artificial lakes, including the Safan Dam Lake on the Saffin River, a tributary of the Tigris. Predominantly Kurdish (Kurds make up 75% of the population), the area is also inhabited by Syriacs, Assyrians, Chaldeans, Arabs and Armenians.

The fourth district of Hasakeh governorate, situated in the northwest, is Ras al-Ain (Serêkaniyê in Kurdish). An ancient city with a history spanning thousands of years, Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain was among the first civilisations in the area and used to be called Washukanni, the capital of the Hurrian Mitanni empire, which rose to prominence in the 14th and 15th centuries BC. The city of Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain is located at the point where the Khabour River crosses into Syria from Turkey, nearly a hundred kilometres west of Qamishlo/Qamishli. Its inhabitants include Kurds, Arabs, Yazidis, Assyrians, Syriacs, Armenians, Chechens, Turkmen and Mardaliyya.

Relations between central authorities in Syria and communities in Hasakeh, not least its Kurdish communities, were characterised by strife and conflict for decades. A longstanding policy, later taken up by the Ba’ath Party after 1963, aimed at assimilating Kurds into the crucible of Arab nationalism. Kurdish political movements were suppressed, and activists arrested, while Kurdish place names were replaced with Arabic ones. Authorities forbade use of the Kurdish language in official settings, prevented expressions of Kurdish identity or culture, and suppressed Kurdish civil rights and political parties through its security apparatus and security branches, which looked on the region as a sensitive military zone.

The Ba’athist regime’s Kurdish policy was given an earlier expression by Mohammad Talab Hilal, head of Hasakeh province’s regional branch of Political Security, in the 1960s. Hilal claimed that there was no such thing as the Kurdish people or a Kurdish nation,[3] describing the Kurdish question as a ‘malignant tumour’ and suggesting that Hasakeh should be ‘purified of foreign elements.’[4] To address the issue, he proposed a range of hardline measures to displace and dispossess Kurds: forcible internal displacements followed by repopulations with Arab loyalist communities, revocations of nationality, and new legislation to restrict Kurds’ ability to work or own property and/or land.[5] Hilal’s vision would be implemented through two events, both with far-reaching impacts for northeast Syria’s Kurdish communities.

The first was the 1962 census conducted in Kobane and Hasakeh through Decree 93/1962.[6] Requested to prove their residency inside Syria since at least 1945 without sufficient knowledge of the process of preparing their documents, 120,000 Syrian Kurds were effectively deprived of nationality overnight. Those rendered stateless were subsequently classified as either ajanib (foreigners) or maktoumeen (unregistered).

The second policy targeting the Kurdish community in Hasakeh came in the form of the “Arab Belt” project. This was a term used to describe the Syrian government’s confiscation of several thousand hectares of fertile agricultural land, belonging to Kurdish farmers in Hasakeh, that was then granted to Arab farmers. In the 1970s, during the completion of the dam, the Syrian government prepared a list of names of Arab peasants who would be transferred from Raqqa’s Tabqa district to Hasakeh province.[7] The government granted these maghmoureen—Arab settlers whose land was submerged during the construction of the Tabqa Dam—agricultural areas based on the rainfall rate. Between the border city of Derik/al-Malikiyah and the Iraq-Turkish border with Syria, these were areas of 150 dunums (an Ottoman unit that is equivalent to an acre); in the border city of Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain, the government gave each family 300 dunums. In autumn 1974, these families were first moved to a temporary camp near Qamishli International Airport; after the government tightened local security measures (to protect from attacks by displaced Kurdish landowners), new villages were constructed, to which maghmoureen families were then transferred. Resettlement ended in the spring of 1975. Over four thousand Arab families (comprising as many as 40,000 people) were transferred from Raqqa province to the Arab Belt region, constituting as much as six percent of the total population of Hasakeh province. Ultimately, hundreds of Kurdish villages and as many as 150,000 people were affected by the population transfer.[8]

Beyond these two policies, structural challenges existed. Hasakeh’s population depended on rain-fed and irrigated agriculture due to the availability of fertile agricultural lands, rivers, and dams. Known as Syria’s food basket, representing 29% of the total cultivated area in Syria, the region is famous for its wheat and cotton, vegetables, legumes and fruits as well as livestock breeding, wool production, dairy and other animal products. However, the Syrian government’s failure to support the regional economy, the deliberate marginalisation of industry and the failure to build large factories and production companies providing job opportunities for the population led to social decline and an increase in unemployment. Hasakeh’s natural resources, including oil, phosphate, and groundwater, were systemically transferred to other areas of Syria. While the people of Hasakeh served and worked in Syria’s interior cities as workers, often without political or economic rights, the government brought in loyalists from central cities, the coast and Damascus to manage Hasakeh’s oil fields through the Syrian Oil Company. These include the al-Jibsah fields in al-Shaddadah as well as the Suwaydiya fields; the fields of Karachuk, Alayan and the Odeh oil field in the city of Tirbespî/al-Qahtaniyah; the Rumaylanfield; the Ma’shuq and Babasih fields; and the Zareba field, which faces the Turkish border. Crucially, the revenues from oil exploitation did not contribute to improving living conditions in Hasakeh or elsewhere in northeast Syria.

Other ethnic groups also faced challenges. Places with an Arab majority—such as southern Hasakeh, which includes the towns and villages of Tal Hamis, al-Hol, al-Shaddadah, al-Arisha and Tal Koçer—were politically and economically marginalised. There were high rates of unemployment here, too, partly caused by limited economic interaction with other areas of Syria and the absence of political activities or public freedoms (other than those questionably afforded by participation with the Ba’ath Party). The lack of job opportunities, security restrictions and the state of poverty prompted many to leave Syria. Tens of thousands of Christians eventually emigrated.

The conflict in Hasakeh

The persecution of Kurdish politicians and activists intensified following the Qamishli Uprising in March 2004.[9] Protests broke out following a football match in the city, when some Arab fans from the al-Fotowwa team shouted racist slogans at fans of the Kurdish host team, al-Jihad. Security forces quickly intervened in the violent altercations that followed, but unrest spread to the rest of the Kurdish areas in Afrin, Aleppo, Kobane and even Damascus. In the six days the protests lasted, Kurdish demonstrators burned the local office of the Ba’ath Party and toppled a statue of Hafez al-Assad; security forces backed by tanks and helicopters cracked down on demonstrators. With between 25 and 40 killed and two thousand Kurdish protestors detained, the events were considered among the worst political unrest to have taken place in northeast Syria. That is, until the Syrian uprising erupted several years later.

Political instability, heavy-handed security policies and ever-deteriorating socio-economic conditions led many of Hasakeh’s residents to join the early protests against Bashar al-Assad once the uprising spread out from the southern city of Dera’a in March 2011. Driven by youth coordinating with protesters in other areas of the country, these demonstrations continued until the beginning of 2012, when they changed from primarily popular protests calling for change to a local violent conflict involving Syria’s armed forces and security agencies, an emerging Islamist armed opposition and increasingly organised Kurdish militia forces.

Despite the structural challenges faced by the people of Hasakeh, many would remember the time prior to the outbreak of the conflict as one in which communities lived in a state of harmony despite the diverse cultures, religions and languages found there. A woman from Tal Tamr said:

We all lived in peace; different groups and peoples, Arabs, Kurds and Syriacs […] everyone coexisted freely with one another. Each person respected the other’s religion. Everyone had the traditions and clothing of their own culture […] and did not interfere with [others].[10]

Another resident of the area also stated that they lived comfortable lives until the conflict broke out:

After the entry of ISIS and the [FSA] into the region, chaos prevailed and the situation turned upside down. But before then, our children used to go to their schools, and we used to go to our work. We were comfortable and our life was easy.[11]

As unrest spread, however, Kurdish political parties were divided over how to respond to the uprising. The KNC, which consisted of 15 Kurdish political parties, was supportive of Syria’s emerging political and armed opposition. A second group of parties, so-called “coordination committees,” saw themselves as more revolutionary and advocated for arming the anti-Assad opposition and confronting the regime with force to bring about change. The third line was taken by the PYD, which joined the National Coordination Committee (NCC) but argued for avoiding armed conflict with any party and focusing on creating an administration to protect Kurdish regions from escalating violence. On 12 July 2012, the PYD and KNC agreed on the formation of the Kurdish Supreme Committee, a governing body for Kurdish-majority regions in Syria, under the auspices of the former president of the KRI’s regional government, Massoud Barzani.

Political differences ensured the agreement did not last long; subsequent agreements such as the Hewler Agreement failed as well. In parallel, from 2011 onwards, the PYD started organising small armed battalions under the umbrella of the YPG. These units, along with some other Kurdish party militants, would erect shared checkpoints in Kurdish areas in Hasakeh as well as Kobane and Afrin. While it had existed before 2011, the formation of the YPG was officially announced in 2012 once the deal between the PYD and KNC fell apart.[12]

The military conflict in Hasakeh began when these forces took control of Kurdish areas in November 2012, following the withdrawal of Syrian government forces.[13] In the same period, armed opposition groups launched an attack on government forces in Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain on 8 November 2012. Several battalions, including the Ghuraba al-Sham Islamic Brigades, Jabhat al-Nusra, the FSA and the Ahfad al-Rasoul Brigades, stormed the city, entering through the border crossing from Turkish territory.[14] The YPG clashed with Islamist battalions. After months of fighting interspersed by more than one ceasefire, on 17 July 2013, the YPG announced it had control of Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain and liberated it from the Islamists.[15]

The arrival of ISIS

The PYD simultaneously worked to establish governance bodies in areas newly under Kurdish control and soon established the Autonomous Administration of northeast Syria (AANES) to govern over three main cantons: al-Jazeera, Kobane and Afrin.[16] Clashes between the PYD and Syrian armed opposition groups continued across Hasakeh province—in areas such as Tal Hamis and in the towns of Tal Koçer and Tal Tamr—until the end of 2013.

By early 2014, ISIS had expanded into Raqqa and Deir Ezzor provinces, and controlled large areas of Iraq. As it increased its territorial control, many of the battalions that had fought the YPG either pledged allegiance to ISIS or were eliminated by the group. Even then, many in Hasakeh were still hopeful that their region would remain largely unaffected. A woman remembered how, at the time:

We never expected that such an explosion could happen and that we would lose innocent civilians for no reason. They were not armed. They were just civilians doing their work and taking care of their families, raising their children and so on. When we followed the news broadcasts about what was going on around us, we would get worried and nervous, but we also used to console ourselves that we were still safe and far away from these events.[17]

This would not last for long. In 2014, ISIS expanded into Hasakeh—which it called its Wilayat al-Baraka (“the blessed province”) in reference to the resources in the region—taking control of Tal Hamis and Tal Brak. Thereafter, it launched a large-scale attack intended to establish control over the area, eliminate the Kurdish presence and control the Syrian-Turkish border. In its trademark style, ISIS launched multiple, simultaneous offensives: from Tal Abyad and Raqqa province towards Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain and the town of Tal Tamr; from the countryside of Deir Ezzor to the towns of al-Shaddadah, al-Hol and al-Sour all the way to Hasakeh city; and from Iraqi territory towards the countryside of Qamishlo/Qamishli and Derik/al-Malikiyah, at the farthest border of the Syrian-Turkish-Iraqi border triangle.

Furthermore, in August 2014, ISIS used the areas it had captured in Hasakeh along the Syrian-Iraqi border as a launching pad for its attacks on the Sinjar region in Iraq’s Mosul after the withdrawal of Iraqi forces from the area. ISIS succeeded in attacking Yazidi areas, causing the displacement of hundreds of thousands of Yazidis and the capture of thousands of families. The YPG responded and was able to open a humanitarian corridor to evacuate more than 12,000 Yazidis, transferring them to YPG-held areas and later transferring them to the KRI. Others remained in the Nowrouz displacement camp near Derik/al-Malikiyah until their areas were liberated from ISIS years later.

By early 2015, ISIS advances had left the group in control of large areas of Hasakeh province, including villages surrounding the city of Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain (though not the city itself) and the area surrounding Tal Tamr (including more than 35 nearby Assyrian villages). The group also controlled the towns of al-Sour, al-Shaddadah and al-Hol, all the way to the southern neighbourhoods of Hasakeh city, where government forces maintained a presence, in addition to dozens of villages around Tal Hamis and the south of al-Rad. The northeastern tip of Derik/al-Malikiyah stayed under YPG control, while the YPG and Syrian government forces both maintained a presence in central Qamishlo/Qamishli.

However, as would become clear soon, this did not mean that ISIS was unable to strike there.

‘There was a fire burning from his back’: Bombings behind YPG lines

ISIS’ military campaign was accompanied by mass-casualty attacks conducted behind YPG lines, which were intended to destabilise the area and demoralise the local population. ISIS repeatedly conducted suicide attacks or remotely detonated car bombs, often with civilians as the main target. Several targeted Qamishlo/Qamishli, which was symbolically important as the Kurdish capital in Syria.

On the morning of 19 August 2015, for example, ISIS targeted the headquarters of the security forces of the Autonomous Administration, the Asayish, in the al-Sina’a area, killing thirteen people, including ten civilians and injuring another 50 civilians. Months later, on 30 December 2015, ISIS targeted two neighbourhoods in the city: al-Wusta, which has a Christian majority, and al-Siyahi, killing sixteen and wounding 22 others.[18]

The following year, on 27 July 2016, a motorcycle and a truck carrying explosives detonated inside a crowded market in western Qamishlo/Qamishli.[19] Consecutive explosions flattened buildings and destroyed cars. A large mushroom cloud of smoke rising over the city was visible from as far away as the Turkish town of Nusaybin, across the border, while the explosion was heard by residents several kilometres away. ISIS claimed responsibility for the explosions soon after, claiming they were intended as retaliation for Kurdish attacks on ISIS forces in Manbij. More than 60 Kurdish civilians lost their lives and over 170 other civilians were injured.

One of the witnesses of the market bombing recalled the devastation, the smell, and the smoke:

A large and deep hole was formed in the main street because of the huge size of the car bomb. The smell of death and burnt bodies was everywhere. People were searching for days to find the remains of innocent people who had died in the explosion. The smoke caused by the explosion was black, as if strange substances were used in the bombing, causing a huge [column] of black smoke. People panicked and died of suffocation because of the smoke.[20]

A father who lost his son in the market bombing described the devastating scene:

I finally arrived at the workshop and found [my other son] crying and screaming. When I asked him about his brother, he told me: “I don’t know where he is.” While we were talking, I noticed someone trying to get out of the rubble. He was unable to crawl, [just] lying face-down.

There was a fire burning from his back. This was the slow-burning cork substance found in refrigerators. His entire back and legs were burning because of this substance. He was hitting the ground.

I stood near his head and realized: “Oh my God, it’s my son!” I was crying my eyes out and said to him: “Get up! Get up, boy! What are you doing?” There was a hole in his head and his back was in flames.[21]

A worker reflected on the loss of his uncle and several customers inside his uncle’s shop at the moment the explosion ripped through the marketplace:

When I arrived at the shop, I started working. While I was doing my work, suddenly, the explosion took place. The sound was terrifying. I left the shop unconsciously. My uncle […] was killed, and so was the child who used to work for him […] who was about eight years’ old. A young man who was working for [my uncle] was killed, too. He had gotten married six months before the bombing took place. Two other people who were inside my uncle’s shop when the explosion happened were killed as well.[22]

Dozens of others were killed. The wife of one of the victims ran towards the blast site, looking for her husband:

I saw the devastation, destruction, and body parts. It was a horrific scene. I searched for my husband for a long time, but I could not find him. I saw his shoe, which had traces of blood on it, and I found his keys in front of the pharmacy. I called my brother, and we went to the hospitals to look for my husband […] but I could not identify him because the corpses had been blown [into pieces]. The bodies were unidentifiable.[23]

The brother of another victim recounted the tragic story of his cousin, a pregnant mother, who died with twins in her womb:

When I arrived at al-Rahma Hospital [in Qamishlo/Qamishli] on the day of the bombing, the corpses had already arrived there. The doctor told me that my nephews were still alive, moving in the womb of their deceased mother. But he asked what I thought should be done.

I told him: “They are six months’ old now. If we decided to operate on the mother now to get them out, will they be able to survive?’

The doctor told me: “No, they won’t survive.”

So, I told him: “If I will keep them with their mother, then this is better for them.” And we wrapped the coffin while they were still inside their mother’s womb. I asked God never to put anyone in a situation like mine.[24]

The bombings had catastrophic consequences for people, causing widespread destruction of civilian property and public infrastructure. Hundreds of families were displaced because of the destruction of their homes or the loss of their workshops, stores, or restaurants. The constant state of terror and fear exacerbated the suffering of those who decided to stay. Some families faced destitution after they lost their household breadwinners, who were often men. One local woman who lost her husband said:

My husband was a taxi driver from the town of Himo. There were passengers with him inside the car, and when he arrived at the scene of the bombing, the big truck had blocked the road, and he was right behind it. The truck exploded. He and two passengers died on the same day, and the other two died after that.

Now my son works and takes responsibility for nine people [in the family] and their daily needs. After I lost my husband and the car that he used for our income, we could hardly secure basic needs given the exorbitant prices.[25]

Qamishlo/Qamishli was not a one-off; several other attacks targeted Hasakeh province between 2014 and 2019. On 14 June 2016, for example, fifteen civilians died and 24 others were injured in a suicide bombing that targeted the eastern entrance of Tirbespî/al-Qahtaniyah. And on 11 December 2015, three trucks armed with explosives targeted an area of Tal Tamr that was close to a crowded Friday marketplace and a local field hospital. More than 60 people died, most of them in the market, while at least 80 others were injured.[26]

In Hasakeh city, ISIS carried out a double bombing on 20 March 2015, the eve of the annual Nowrouz celebrations. Over 50 people attending were killed, and more than 150 were injured. A year later, an ISIS suicide bomber targeted the wedding of a Kurdish family on the outskirts of the city, killing more than 50 family members and attendees.[27] A woman who was there summed up how many in the area still feel today: “I am psychologically exhausted. Just mentioning ISIS […] takes me back to those events.”[28]

The trauma of ISIS violence does not heal easily. One of the victims, a journalist, reflected on the psychological effects of the violence that people suffered:

After the death of my daughter, our lives completely changed. Even now, we go to the graves every week because we find some comfort in being next to [our] daughter.

What saddens me most is that my daughter was a civilian. She did not know about any weapons or carry any weapons at any point in her life. She dreamt of developing the municipality, finding new ways to carry out public work and building municipalities so that women could be employed there.

However, with her death, all these things disappeared. I lost interest in my work and my life. I stopped working because of my grief and hopelessness in the wake of my daughter’s death. My wife suffered from grief over her only daughter being brutally killed.

As a result, I sent my son to a European country as I was afraid for him after what happened to his sister—even though he was studying medicine in Damascus. The fear for him prompted me to do so. My wife and I lost the taste for life. The death of my daughter created a backlash for me towards all religions, especially Islam.[29]

‘The villages are completely empty’: Displacement of minorities in Hasakeh

In Hasakeh, home to a profoundly diverse patchwork of ethnic, religious and sectarian communities, ISIS often singled out and targeted Christian communities along the frontlines and in towns and villages not under the group’s control.

A Christian man from the countryside of Qamishlo/Qamishli said:

Our village was made up of 24 families. Now, only three families remain. Imagine only three inhabited houses; the rest have all migrated. [ISIS’] targeting [of] Christians and Kurds was more violent and harsher. One of the Assyrian villages has no traces [left] whatsoever.

Qalaat al-Hadi village has one Christian family now; before, there were a hundred houses there. Tal al-Alo village used to have a hundred families. Now, there is not a single family in it.

ISIS destroyed our families. Everyone migrated because of ISIS. The villages are completely empty. Frankly, everyone suffered from ISIS, but we, the Syriacs and Christians, suffered more than everyone else because our existence is in danger now. Since 1915 [during the Ottoman massacre of Syrian Christians], this is the biggest migration from our villages; even in 1915, we were not impacted in the same way.[30]

The man’s village was among those attacked by ISIS. While some of the residents of the village fled, others did not get away in time or decided to stay:

We were sitting in the village, as usual, in our homes. Suddenly, a group of ISIS members came in four-wheel-drive pick-ups. They were all armed and masked. They started shooting to terrorise the villagers. Then they started entering the houses and expelling people. We were afraid.

Some of the people fled, but the majority did not have enough time to escape. ISIS members started looting anything lightweight and expensive from the houses. They kidnapped me with a group of my friends. I was the target of kidnapping because I am Christian. They stole two cars from me as well as everything in my house. They left nothing. They even removed the doors and windows, put them in their cars and took them.

We stayed in their custody for 12 days. They tortured us for nine consecutive days and beat and cursed us. They used intimidation and threatened to behead us. Every day at dawn, around two o’clock in the morning, a Tunisian man entered the cell, put a sword to my neck and threatened to behead me.[31]

Similar attacks were commonplace in the Tal Tamr area. Between 23 and 26 February 2015, for example, ISIS launched a massive attack on a group of Assyrian villages along the southern bank of the Khabour River, near Tal Tamr, using about three thousand fighters and multiple tanks. Nearly a dozen villages were seized, and 220 Assyrian Christian residents were kidnapped during the raids, although local sources reported that as many as four hundred people were kidnapped in total.[32]

In the countryside of Tal Tamr and Qamishlo/Qamishli, ISIS also systematically targeted churches. By attacking the places of worship of non-Muslims, ISIS sought to displace populations who had historically lived in the region. On 15 April 2015, ISIS fighters blew up the Virgin Mary Church, constructed in 1934, in the Assyrian village of Tal Nasri in the western countryside of Tal Tamr.[33] ISIS also burned down the historic Tal Hormuz Church, one of the oldest churches in Syria, destroyed the Qabr Shamiya Church and Church of Tal Jazeera and targeted the Church of St. Thomas in the village of Umm al-Kif.[34]

One of the women in charge of a church in Ghardouqa, in Qamishlo/Qamishli’s countryside, recounted how ISIS raided her village. ISIS had settled in a nearby village and carried out the attack from there:

The church was destroyed. The houses around it were looted, their precious contents stolen, and then burnt down. The crosses were stolen. I told the priest about it; he said we couldn’t do anything. We went and photographed the great damage. They even stole the doors and windows of the monastery and the houses around it. They did all this to us because we were Christians.

A few days later, they kidnapped the son of our mukhtar […] who died after his release. [He] was healthy and strong but died because of the torture and the beatings.[35]

Kurds in ISIS-held areas were initially treated with greater leniency because most Kurds are Sunni Muslims; this policy changed as Kurdish resistance to ISIS fanned out from Kobane.

Later, and unlike Christians, Kurds were targeted because ISIS considered them to be “atheists” and because of Kurdish groups’ armed resistance against ISIS rule. ISIS bombings frequently targeted Kurdish-majority cities, while the group also attacked Kurdish villages. The result, in some ways, was a brutal, extreme continuation of the kind of discriminatory anti-Kurdish policies pursued for decades by Syria’s Arab rulers. One of the residents of the Kurdish villages in the countryside of Qamishlo/Qamishli reflected on the displacement:

Our village was surrounded by Kurdish and Arab villages. The Kurdish villages in Tal Hamis district were destroyed and looted […] because they were Kurdish. Our village was not destroyed because there are some people from the Arab community [living there].[36]

The impact of the violence reverberates to this day. Victims pointed out that there have not been “real reparations” to cover people’s losses.[37]

Meanwhile, the wounds of ISIS’ highly sectarianized, community-based violence have not healed. According to the Christian man from the Qamishlo/Qamishli countryside, attacks on Christians were deeply ideological. He argued that that ideology, instilled by ISIS from a young age, continues to shape relations in Hasakeh today:

ISIS had schools or centres teaching purely extremist religious curricula that had nothing to do with education. Children were influenced by ISIS, which trained them in jihad and graduated them as suicide bombers. As such, our children’s thinking […] changed. Even locals from the region hate the Assyrians and Christians and consider them to be infidels.[38]

Others saw the continued presence of ISIS-instilled racism as standing in the way of reconciliation. According to a Kurdish villager:

ISIS was able to sow discord and racism among the people of the region. There were people who did not become ISIS members, [but who lived] in our lands and homes in ISIS’ name. They exploited our agricultural lands. This created a lot of hatred and destroyed the idea of tolerance and forgiveness in the region.[39]

‘If he doesn’t come back, it means he was killed’: Forced disappearance, torture and executions in al-Shaddadah

Arrests and forced disappearances, kidnappings and torture were common features of life under ISIS rule in Hasakeh. According to the UNHRC, the group’s use of torture as part of attacks against Hasakeh’s civilian population amounted to war crimes and crimes against humanity.[40] While ISIS was more lenient toward Arab villages, any Arabs that did not show sufficient support for ISIS’ ideology would be subjected to harsh penalties.

The social regime imposed upon the population was strict and all-encompassing, as one man from the predominantly Arab town of al-Shaddadah described:

The security situation […] was terrifying. There were many cases of execution, kidnapping and killing. They were not able to defend themselves, and there are no apparent reasons for the actions of ISIS towards the people. Sometimes they stormed some houses and took people, and no one knew where they took them. They never returned.

Many of al-Shaddadah’s residents are still missing. Their families do not know anything about them, whether they died or alive.

No one was able to speak to ISIS or leave their children to play in the neighbourhood due to the fear and terror we lived with. We couldn’t even talk amongst ourselves about ISIS because we were so afraid, and we were always exposed to arrest for no reason.[41]

Another man from the town added:

ISIS would force everyone to fast, pray, not to talk about anyone and to wear Shari’a clothes. They would take zakat from shops, from anyone who owned animals such as sheep, cows, camels and crops, and from anyone wanted by [the group].[42]

A minor violation could have devastating consequences. According to a father whose son was kidnapped in al-Shaddadah:

My son was going to the market. He was wearing shorts, and ISIS arrested him and accused him of wearing infidel clothing. Until today, he is still missing. I searched for him everywhere, but I did not find him. Later, they told me that he was accused of being a member of the Syrian army and that he was an agent of the regime. [43]

Hundreds remain missing until today. Although many relatives know that the chance that their kidnapped loved ones will return is very slim, without confirmation, they never fully give up hope. The brother of an abductee said that:

We do not have any news about my brother. We knew that those who were kidnapped by ISIS for more than fifteen days never returned, but we still hope that my brother will return. If he doesn’t come back, it means he was killed—like many Kurds who were killed by ISIS in Iraq and Syria.[44]

Others lost loved ones in public executions, which ISIS used to instil terror and subjugate populations. A man from al-Shaddadah recounted how ISIS killed his son:

My neighbour shouted in a loud voice: “Abu Abboud, there’s going to be an execution today.” At this point, I felt as if I was paralysed, and I did not know what to do. I went back home and told my wife. She screamed out of fear and prayed to God that our son would not be among them. She told me to go and check his name.

At about 11am, while I was praying in the house, someone knocked loudly on the door. Our neighbour shouted: “They executed Obaid! They announced his name, and she heard them saying Obaid from the house of Abu Abboud.”

They beheaded my son with a sword. I did not see my son’s body—although ISIS used to hang the bodies in the square, they executed my son and took him with them to a place unknown to me.

I was shocked and traumatised. I suffer from a sleeping disorder, and I have nightmares. I am so afraid.[45]

‘No one wanted her once she was over 17’: Violations against women and girls

Like other territories under the control of ISIS, Hasakeh witnessed horrific abuses against women and girls. Slavery and forced marriages, including those of underage girls, were common:

When we were in al-Shaddadah, ISIS brought Yazidi and Assyrian women and sold them there or gave them to ISIS commanders. Then, they would transfer whoever was left to the city of Raqqa. ISIS used to offer them to whoever wanted a woman. These women were taken for pleasure. Few were married in the Islamic way.

Also, when a husband of a woman from the city died, they would get [the widow] married after seven days under the pretext that they were in a state of war. One day, a 50-year-old man married an 11-year-old girl because her father was greedy and wanted the financial revenues that the groom would give him. The father claimed that the child wanted to marry a 50-year-old man. They always got minors married. No one want[ed] her once she was over 17.[46]

The wife of an ISIS member was interviewed for this report. Speaking from her home in one of the many camps in northeast Syria for ISIS-affiliated women and children, she claimed she was forced into marriage against her will:

My husband, an ISIS fighter, used to beat me all the time. Throughout the two years [we were married], he beat me constantly. One day, he wanted to detonate an explosive belt while it was on me and he hit me with his rifle as well. He once fired two bullets at me, but he didn’t hit me. It was all because I was visiting my family. I began to see my family secretly.

He was already married at the age of 29 when he came to propose to me. I was in the market when he saw me and started following me until he figured out where I lived. He proposed to me through my brother, but my brother did not agree. The consent should be given by me. I risked my life for the sake of my family and my desire not to harm them. He was a fighter in ISIS, and he could do anything.

When we were in Raqqa, he told me to blow myself up if the SDF came. I told him I wouldn’t: I couldn’t hurt anyone and was not influenced by [ISIS] or their ideas and projects. I am Kurdish and all my family members are married to Kurds. My mother’s sisters are from Jarabulus. We are known for our Kurdishness, although […] we don’t speak Kurdish.[47]

ISIS’ leagacy lives on in the camps

After April 2015, the tide turned for ISIS in Hasakeh . Kurdish and Christian militias, as well as some Arab tribal groups, such as the al-Sanadid Forces,[48] recaptured large parts of the Tal Tamr and Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain countryside, supported by airstrikes from the US-led Coalition.[49] By the end of the month, the YPG had reached the provincial boundary between Hasakeh and Raqqa, and slowly, preparations for the offensive on ISIS’ self-proclaimed capital began.

Even then, though, there were intense battles to liberate all areas of Hasakeh province. ISIS still held positions close to Hasakeh city, and a car bomb attack on 30 May 2015 in Hasakeh killed 50 pro-government troops.[50] Government forces repelled an attack on Hasakeh city by ISIS in early June.[51] ISIS opened another offensive later that month, which left several parts of the city in ruins, although this was also repelled by the government and YPG forces. Finally, in early August, the YPG declared the full liberation of Hasakeh city.[52]

Following the creation of the SDF in October 2015, another offensive to retake all remaining ISIS-held territory in southern Hasakeh was launched.[53] In November, the area around al-Hol was brought under SDF control;[54] in early 2016, the SDF took control of al-Shaddadah and, with it, most of Hasakeh province. Later in 2016, the SDF clashed with pro-Assad forces in Qamishlo/Qamishli and Hasakeh city. This left the Kurdish authorities with increasing control over both cities.[55]

It would not be the end of Hasakeh’s troubles with ISIS. The province came to host various camps of suspected ISIS fighters and their families, managed by the Autonomous Administration and SDF. The largest of these camps, al-Hol, hosted up to 53,000 people of 60 nationalities by the end of 2022 (down from a total of 76,000 in early 2020).[56] The camp grew as women and children were displaced from ISIS-controlled areas of Syria and Iraq and ISIS gradually lost more and more territory.

Nowadays, while most camp residents are from Syria and Iraq, around 10,000 are likely third country nationals. As many as 64% of the camp’s residents are estimated to be children.[57] Hardened ISIS supporters continue to radicalize people in the camp, which is also rife with crime and lacking in adequate medical care, basic services and education opportunities.

Another camp in Hasakeh province, al-Roj, is located near the town of Kari Rash, east of the main road that links Qamishlo/Qamishli and Derik/al-Malikiyah. Established in 2015 to house displaced Syrians fleeing ISIS attacks, al-Roj began receiving Yazidis and other Iraqi refugees fleeing ISIS violence on the other side of the border; however, it was later turned into a centre for ISIS-affiliated foreign nationals in 2017. The camp’s population steadily increased. Following the defeat of ISIS by the SDF and US-led Coalition at Baghouz in 2019, the Autonomous Administration and SDF expanded al-Roj to accommodate more people. Other camps in the area include those in al-Arisha and Washo-Kani.

The aftermath

Post-ISIS, Hasakeh has not been spared further conflicts and displacements. Up to 180,000 people were displaced from the Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain region during the 2019 “Peace Spring” offensive launched by Turkey and the Turkey-backed SNA against the YPG and SDF,[58] as US forces temporarily withdrew forces from the area.[59] In late November 2022, Turkey conducted an extended aerial campaign against SDF targets in Hasakeh;[60] Turkish President Erdogan vowed a ground invasion would follow, although this has not yet materialised.[61] Nevertheless, the continued threat of a Turkish-led incursion into northeast Syria has diverted the SDF’s full attention from managing the camps and prisons where ISIS fighters are detained.

ISIS, meanwhile, has demonstrated its ability to still conduct serious operations in Hasakeh. On 20 January 2022, groups affiliated with ISIS attacked the “Ghuweran” or al-Sina’a prison, located on the southern outskirts of Hasakeh city, which housed thousands of former ISIS fighters. The attack, which lasted for nine days, ended with the deaths of dozens of ISIS fighters and ISIS detainees inside the prison, although between 30 and 100 ISIS leaders managed to escape. According to an SDF statement, 117 members of the SDF and its prison garrison lost their lives.[62] US forces, which remain in Hasakeh province to fight ISIS despite protests from the Syrian government and its allies, also joined the SDF to put down the prison uprising.[63]

There are in total 20 other prisons across northeast Syria, several of them in Hasakeh (including facilities in Qamishlo/Qamishli and al-Shaddadah).[64] As places where hardened ISIS fighters remain detained indefinitely without prospects for a long-term solution, they will remain targets for ISIS cells looking to rebuild their forces well into the future.

Footnotes

[1] These regions were named by the Syrian government in Damascus, but renamed by the Autonomous Administration of northeast Syria (AANES) following its establishment of de facto control over the region during the course of the Syrian conflict. The Autonomous Administration renamed Hasakeh “Rojava.” Furthermore, the Autonomous Administration divided the region into two main cantons: Qamishlo Canton, which includes the district of Qamishlo/Qamishli and Derik district/Al-Malikiyah; and the Hasakeh Canton, which includes Hasakeh and Serêkaniyê/Ras al-Ain. Kudish-majority districts and place-names are referred to by their Kurdish and Arabic names throughout the text.

[2] Map Action, ‘Syria District Maps: Al-Hasakeh’ (4 July 2016) <https://maps.mapaction.org/dataset/217-2795/resource/398dcb1b-3367-43a9-87f7-5ab51229cc85> accessed 16 August 2023.

[3] Mohammad Talab Hilal, A Study on the Aljazeera Governorate from National, Social, and Political Aspects (Ar.) (Erbil, 2001), pp.8-9.

[4] Ibid., pp.4-10.

[5] Ibid.

[6] The decree to conduct the census in Hasakeh was based on Legislative Decree 1/1962, dated 30 April that year, and on the decision issued by the Council of Ministers, Decision 106/1962. The decree, now known as the “1962 Hasakeh Census Decree” included in its first article the following: ‘A general census of the population will be conducted in Hasakeh Governorate in one day, the date of which will be determined by a decision of the minister of planning based on the proposal of the minister of interior.’

[7] The transfer order was implemented based on a decision issued by the regional leadership of the Ba’ath Party. The government assigned both the assistant regional secretary of the Ba’ath Party, Muhammad Jaber Bahbouh, and a member of the regional leadership, Abdullah al-Ahmad, to follow up on the settlement operations and to secure housing for families that would be transferred to Hasakeh province.

[8] HRW, ‘The Silenced Kurds’.

[9] Hugh Macleod, ‘Football fans’ fight causes a three-day riot in Syria” The Independent (London, 15 March 2004) <https://www.independent.co.uk/news/world/middle-east/football-fans-fight-causes-a-threeday-riot-in-syria-5354766.html> accessed 16 August 2023.

[10] Individual testimony #50, focus group session 3.

[11] Individual testimony #52, focus group session 3.

[12] Uppsala Conflict Data Program (UCDP), ‘Syria: Rojava Kurdistan’ (n.d.) <https://ucdp.uu.se/additionalinfo/13042/1> accessed 15 August 2023.

[13] Charles Lister, The Syrian Jihad: Al-Qaeda, the Islamic State and the Evolution of an Insurgency (Oxford University Press, 2015), p.96.

[14] Al-Arabiya News, ‘Kurd-jihadist firefights rage in northern Syria’ AFP (18 January 2013) <https://english.alarabiya.net/News/2013/01/18/Kurd-Jihadist-firefights-rage-in-northern-Syria> accessed 16 August 2023.

[15] Donna Abu-Nasr, ‘Syrian Kurds Expel Radical Islamists From Town, Activist Says’ Bloomberg (17 July 2013) < https://www.bloomberg.com/news/articles/2013-07-17/syrian-kurds-expel-radical-muslims-from-town-activist> accessed 16 August 2023.

[16] Lister, Syrian Jihad, p.154.

[17] Individual testimony #6.

[18] Reuters, ‘Twin suicide bombs in northeast Syria kill or wound dozens – Kurds, monitoring group’ (30 December 2015) <https://www.reuters.com/article/mideast-crisis-syria-kurds-idINKBN0UD1VC20151230> accessed 16 August 2023.

[19] France24, ‘Scores killed after deadly blast rocks Kurdish-majority Syrian city’ (Paris, 27 July 2016) <https://www.france24.com/en/20160727-syria-kurdish-qamishli-bomb-blasts-islamic-state> accessed 16 August 2023.

[20] Individual testimony #1.

[21] Individual testimony #7.

[22] Individual testimony #24.

[23] Individual testimony #6.

[24] Individual testimony #8.

[25] Individual testimony #17, focus group session 2.

[26] Reuters, ‘Islamic State truck bombs kill up to 60 people in Syrian town: Kurds’ (11 December 2015) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-northeast-idUSKBN0TU0NS20151211> accessed 16 August 2023.

[27] United Nations Human Rights Council (UNHRC), ‘10th Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’ A/HRC/30/48 (13 August 2015), para.125.

[28] Individual testimony #62, focus group session 3.

[29] Individual testimony #30.

[30] Individual testimony #11.

[31] Ibid.

[32] CBC, ‘ISIS has now abducted 220 Christian Assyrians, activists say’ (26 February 2015) < https://www.cbc.ca/news/world/isis-has-now-abducted-220-christian-assyrians-activists-say-1.2973069> accessed 18 August 2023.

[33] Reem Chamoun and Sargon Yousef, ‘Demolished Assyrian village by ISIS becomes a refuge for IDPs’ North Press Agency (10 December 2019) <https://npasyria.com/en/38302/> accessed 16 August 2023.

[34] Sam Sweeney, ‘The Village Church of Tel Hormiz: A story of Syrian Christianity in adversity’ Catholic Herald (22 January 2021) <https://catholicherald.co.uk/the-village-church-of-tel-hormiz-a-story-of-syrian-christianity-in-adversity/> accessed 28 September 2023.

[35] Individual testimony #75, focus group session 1.

[36] Individual testimony #30.

[37] Individual testimony #1.

[38] Individual testimony #11.

[39] Individual testimony #30.

[40] UNHRC, ‘9th Report of the Independent International Commission of Inquiry on the Syrian Arab Republic’ A/HRC/28/69 (5 February 2015), para.171.

[41] Individual testimony #46.

[42] Individual testimony #66.

[43] Individual testimony #64.

[44] Individual testimony #43.

[45] Individual testimony #37.

[46] Individual testimony #66.

[47] Individual testimony #68.

[48] The al-Sanadid Forces are a tribal militia associated with the Arab Shammar tribe, originally formed to fight ISIS in northeast Syria.

[49] SOHR, ‘Advances for regime forces in Idlib and Tal Tamir countrysides’ (9 May 2015) <https://web.archive.org/web/20150518094651/http://www.syriahr.com/en/2015/05/advances-for-regime-forces-in-idlib-and-tal-tamir-countrysides/> accessed 16 August 2023.

[50] SOHR, ‘At least 50 members of the regime forces and allied militiamen killed and wounded in an attack launched by IS on the city of al- Hasakah’ (30 May 2015) <https://www.syriahr.com/en/18895/> accessed 16 August 2023.

[51] Al-Arabiya News, ‘Syria army pushes ISIS back from Hasaka’ (7 June 2015) <https://english.alarabiya.net/News/middle-east/2015/06/07/Syria-army-pushes-is-back-from-Hassakeh> accessed 16 August 2023.

[52] YPG, ‘August 1: Strong Resistance Finally Results in Full Liberation of the City Hasakah from the ISIL Terrorists’ (YPGRojava, 2 August 2015) <https://web.archive.org/web/20160302164405/http://dckurd.org/2015/08/02/august-1-strong-resistance-finally-results-in-full-liberation-of-the-city-hasakah-from-the-isil-terrorists/> accessed 16 August 2023.

[53] John Davison, ‘New U.S.-backed Syrian rebel alliance launches offensive against Islamic State’ Reuters (31 October 2015) <https://www.reuters.com/article/us-mideast-crisis-syria-idUSKCN0SP0EA20151031> accessed 16 August 2023.

[54] AFP, ‘Syrian Kurdish-Arab alliance captures nearly 200 villages from IS’ (Paris, 16 November 2015) <https://web.archive.org/web/20151118111144/http://www.france24.com/en/20151116-syrian-kurdish-arab-alliance-captures-nearly-200-villages> accessed 16 August 2023.

[55] The Japan Times, ‘Under fresh truce, Kurd forces look to keep areas taken from Syria regime’ (Reuters, 25 April 2016) <https://www.japantimes.co.jp/news/2016/04/25/world/fresh-truce-kurd-forces-look-keep-areas-taken-syria-regime/> accessed 16 August 2023.

[56] Médecins Sans Frontières, ‘A lost generation live in fear inside Syria’s Al-Hol Camp’ (7 November 2022) <https://www.msf.org/generation-lost-danger-and-desperation-syria%E2%80%99s-al-hol-camp> accessed 16 August 2023.

[57] Kathryn Achilles and others, “Remember the armed men who wanted to kill mum”: The hidden toll of violence in Al Hol on Syrian and Iraqi Children (2022) <https://resourcecentre.savethechildren.net/pdf/children_conflict_al_hol_camp_syria_2022.pdf/> accessed 28 September 2023.

[58] United Nations, ’ Nearly 180,000 displaced by northeast Syria fighting as needs multiply: UN refugee agency (22 October 2019), https://news.un.org/en/story/2019/10/1049761, accessed 15 August 2023.

[59] BBC, ‘Trump makes way for Turkey operation against Kurds in Syria’ (London, 7 October 2019) <https://www.bbc.com/news/world-middle-east-49956698> accessed 16 August 2023.

[60] Ali Kucukgocmen and Suleiman al-Khalidi, ‘Turkish air strikes target Kurdish militants in Syria, Iraq after bomb attack’ Reuters (20 November 2022) <https://www.reuters.com/world/middle-east/turkish-air-strikes-hit-villages-northern-syria-sdf-2022-11-19/> accessed 16 August 2023.

[61] Hogir Al Abdo and Abby Sewell, ‘Erdogan vows ground invasion of Syria, Kurds prepare response’ PBS (23 November 2022) <https://www.pbs.org/newshour/world/erdogan-vows-ground-invasion-of-syria-kurds-prepare-response> accessed 16 August 2023.

[62] Mohammed Hassan and Samer al-Ahmed, ‘A closer look at the ISIS attack on Syria’s al-Sina Prison’ (Middle East Institute, 14 February 2022) <https://www.mei.edu/publications/closer-look-isis-attack-syrias-al-sina-prison> accessed 16 August 2023.

[63] Jane Arraf and others, ‘U.S. Troops Join Assault on Prison Where ISIS Holds Hostage Hundreds of Boys’ The New York Times (New York City, 24 January 2022) <https://www.nytimes.com/2022/01/24/world/middleeast/syria-prison-isis-hasaka.html> accessed 16 August 2023.

[64] Hassan and Ahmed.