By Edoardo Camilli

When we talk about integrating technology with the human dimension of peacebuilding and conflict, it’s important to recognise that the current generation experiences conflict differently from previous ones. This is not only due to technological advancements but also because the dynamics of conflicts themselves have changed. We now see the emergence of new actors and different forms of disinformation. Young people are often the first victims of these conflicts but also the first to take to the streets, creating activist movements and demanding peace from their governments.

The conflict in Ukraine illustrates how dynamic and hybrid modern conflicts can be. Understanding these conflicts deeply and leveraging technology to do so is crucial. Artificial intelligence (AI) and large language models can assist analysts by collecting and analysing data more efficiently, providing policymakers with better insights at tactical and strategic levels, and understanding the narratives driving the conflicts.

However, while AI and technology are useful, they also pose significant risks, such as the spread of disinformation. A notable example is the incident in June 2022, when the mayors of Berlin, Madrid, and Vienna had separate video calls with someone they believed to be the mayor of Kyiv, Vitali Klitschko. It took the mayor of Berlin 15 minutes to realise she was speaking to a deep fake. Following the incident, the office of Berlin’s Mayor, Franziska Giffey, released a statement saying that: “There were no signs that the video conference call wasn’t being held with a real person,”. This incident highlights the ease with which technology can be used to deceive and influence narratives, affecting conflict resolution processes.

There is no single solution to prevent the spread of hate speech and disinformation. It requires a multifaceted approach, including legal measures, technological developments, and, most importantly, education in critical thinking. Social media providers must step up to provide censorship where necessary, and AI can help flag content for review by human fact-checkers. But the most crucial component is education. People must learn to use media responsibly, verify information, understand the agenda behind it, and distinguish between what is real and what is fake.

For instance, AI currently struggles with accurately reproducing human hands. If you see an AI-generated image where the hands are blurred or have an unusual number of fingers, it’s a sign that something is off. Understanding these details helps in identifying fake content.

The future of AI is uncertain. Even the most advanced developers in Silicon Valley express concerns about AI’s capabilities and where it might lead. The rapid advancements in large language models, robotics, and autonomous weapons are creating a landscape where the implications are not fully understood.

Initiatives like the European AI Act are crucial but also create a global divide. Countries with stringent regulations might fall behind in certain technological capabilities compared to those without such regulations. This competition complicates efforts in conflict resolution and understanding.

In these dark times, it requires concerted efforts from politicians, tech experts, and civil society to navigate these challenges. Educating the public about how AI works, its biases, and its potential for discrimination is essential. For example, AI used in HR could exclude people of colour if the training data is biased toward white Americans or Europeans.

Transparency in AI development and data usage is vital to ensure it helps us find better solutions.

Integrating technology with the human dimension of peacebuilding is complex but necessary. It demands a balanced approach, combining legal, technological, and educational strategies to manage the risks and leverage the benefits of AI and other technologies in promoting peace and resolving conflicts.

Edoardo Camilli is CEO and Co-Founder, Horizon Intelligence (Hozint) and Friends of Europe’s European Young Leader (EYL40)

By Edita Velic

Coming from the Western Balkans, particularly Bosnia and Herzegovina, I witness first-hand the daily struggles of a region where war wounds are still fresh and conflict remains a constant threat. Hatred, often fuelled by politicians, permeates our society. A critical question we must address is the accountability of those in power—politicians and opinion leaders whose voices shape public perception. Without accountable leadership, achieving lasting peace remains a distant dream.

In Bosnia and Herzegovina, the Dayton Peace Agreement will celebrate its 30th anniversary next year. Despite this milestone, true peace remains elusive, and recent events have reignited old tensions. The recent UN resolution on genocide, for instance, has sparked new arguments within my country and the region. This underscores a fundamental truth: peace cannot flourish without leaders committed to accountability and reconciliation.

Young people bear the burden of past generations’ conflicts, yet they also carry the potential for change. Within the Western Balkans, young political leaders from various backgrounds cooperate daily, demonstrating that collaboration is possible despite the divisive rhetoric of senior politicians. Historical examples show that significant progress can be made when leaders take responsibility for transforming conflict into cooperation. The European Union, born from the devastation of World War II, stands as a testament to this potential. It is a beacon of diversity and peace, illustrating how former enemies can become allies.

We must honour and learn from those who have suffered the most, like the mothers of Srebrenica. Despite losing their families, they continue to advocate for peace, refusing to perpetuate hatred. Their example is a powerful reminder that reconciliation is possible and that future generations must build on their legacy of peace.

One initiative that highlights the potential of youth in peacebuilding is the Youth Council of the Federation of Bosnia and Herzegovina, organised by the Regional Cooperation Council. Young people involved in this project have raised critical issues, such as mental health, affected by the daily narratives of conflict and division. Acknowledging these issues is the first step towards creating a healthier, more peaceful society.

Change is happening, albeit slowly. Some areas are experiencing fewer overt conflicts, though tension remains in others. It is crucial to recognise and address these dynamics, ensuring that progress is not undone by new provocations. Imposing laws, such as those criminalising genocide denial, though controversial, have contributed to this progress. These measures, while imperfect, are steps towards ensuring accountability and promoting reconciliation.

Civil society plays a vital role in this transformation. Educational reforms are essential, particularly in a country where curricula differ drastically between entities. In some areas, war criminals are taught as heroes, perpetuating division and conflict. To build a peaceful future, young people need education that fosters understanding and reconciliation, not one that glorifies past atrocities.

Achieving lasting peace in the Western Balkans requires accountable leadership and the active participation of youth. We must draw on historical lessons and honour those who have suffered, using their experiences to guide our path forward. By promoting intergenerational dialogue, educational reform, and the active involvement of young leaders, we can transform the region from one of conflict to one of lasting peace. The journey is challenging, but with commitment and cooperation, it is within our reach.

Edita Velić is a youth activist and former chairperson of the Assembly of Bosnian-Podrinje Canton Goražde

By Alliyah Logan

In any conversation about conflict resolution, the inclusion of girls and women is non-negotiable. When girls and women are absent from these discussions, the solutions fall short. This is because women bring unique perspectives, focusing on those most affected by issues such as war and famine. In my role as a consultant for UNICEF, I’ve had numerous conversations with young people, especially young girls, about gender equality. The consensus is clear: gender equality often takes a back seat to other issues, which is a significant oversight.

It is essential to involve young people in these discussions. However, advocating for a complete exclusion of older generations is counterproductive. Instead, we need intergenerational dialogue where the innovative ideas of youth are combined with the experience of older generations. This collaboration can lead to substantial and effective change.

Messaging and communication are vital in reaching and engaging more young people, including young men. Data and quantitative information can be compelling tools in these efforts. For instance, presenting data that shows how investing in girls’ education can boost a country’s GDP can be a powerful motivator for world leaders. While it’s unfortunate that such arguments need to be framed in economic terms, they are often necessary to drive action.

Reimagining how systems and bureaucracies function is crucial for integrating young people into decision-making roles. My work with UNICEF highlighted the challenges young people face in navigating bureaucratic structures. Therefore, it’s not enough for older generations to allow young people into the room; they must also hire, listen to, and genuinely consider their input. Effective mentorship plays a significant role here. Mentors can guide young people, helping them navigate and eventually transform these systems.

To everyone reading this, I encourage you to mentor a young person. The impact of mentorship cannot be overstated. It provides young people with the belief in their potential and the support they need to succeed. This is especially important for young girls, who need to see that investments in their education and mentorship are valued.

We live in a time where people are increasingly frustrated with broken promises from politicians. There is a growing need to rethink how we elect leaders and ensure they uphold ethical standards. In the context of conflict resolution, it’s vital to understand that peacemaking is just one part of peacebuilding. The issues discussed today—gender equality, trusted media, diplomacy, and ethical leadership—are all integral to peacebuilding.

Politicians and world leaders have often been reactive rather than proactive. This needs to change. We must implement steps to prevent issues from escalating into full-blown conflicts. As an American, I often look to Europe for examples of how to address these challenges effectively. The European Institute of Peace and the European Union have done commendable work in advocating for women’s rights and education. Their success serves as a motivation for other parts of the world to improve livelihoods and human rights.

In conclusion, the involvement of girls and women in conflict resolution is indispensable. Their perspectives enrich the dialogue and lead to more comprehensive solutions. Combining the energy and fresh ideas of young people with the wisdom and experience of older generations can drive substantial change. By rethinking our systems, valuing mentorship, and ensuring proactive leadership, we can build a more inclusive and peaceful world.

Alliyah Logan is education advocate, and consultant at UNICEF

By Clionadh Raleigh

The landscape of conflict has drastically changed over the past two decades. Traditional civil wars are no longer the primary form of conflict. Instead, a growing number of people are affected by violence perpetrated by gangs, militias, cartels, mobs, and rioters. This shift necessitates an evolution in our approach to peacemaking, as many of these actors are not interested in peace but rather in the power and resources that violence can bring.

In recent years, the most significant increases in conflict have occurred not in failed or fragile states but in middle and high-income nations, including those with democratic features. This underscores that modern violence is a feature of political competition and can occur at any level of governance. Therefore, our approach to engaging with these actors must be similarly political, recognising that the motivations for violence are deeply intertwined with the quest for power.

One disturbing trend is that engaging in violence is not sufficiently costly. Until the consequences of violence outweigh its benefits, we will continue to see its prevalence. Peacemaking efforts need to address this imbalance, making violence a less attractive option. This requires a comprehensive understanding of the specific political, economic, and social incentives that drive conflict in different regions.

The diversity of conflicts across the globe means there is no one-size-fits-all solution. The strategies used to address violence in Colombia, for example, will differ from those in the Philippines, Mexico, Haiti, or Sudan. Each context requires tailored approaches that consider the unique drivers of conflict and the local political dynamics.

Inclusion is often touted as a key strategy for preventing conflict. However, inclusion alone is not a panacea. While inclusive political processes can help stabilise a country in the long term, they can also lead to increased violence in the short term. This is particularly true when political actors use violence to maintain their access to power. A study of African states over the past 20 years found that more inclusive national cabinets were associated with a higher likelihood of militia activity. This suggests that politicians invested in violence to secure and maintain their positions of power.

Thus, while political engineering aimed at creating more inclusive governance structures is essential, it must be approached with caution. Integrating excluded groups into the political process can lead to greater instability and conflict in the short term. The challenge is to balance these short-term risks with the long-term goal of sustainable peace.

The complexity of modern conflicts means that our response strategies must also evolve. Traditional peacemaking tools and approaches are often insufficient for dealing with the multifaceted nature of contemporary violence. For example, engaging with cartels, insurgent groups like the Taliban, or state governments involved in assassination campaigns requires different tactics and strategies. This calls for a broader range of tools and a willingness to experiment with new approaches to conflict resolution.

One critical aspect of modern peacemaking is recognising that not all conflicts will have a peace process led by external actors. Local solutions and local leadership are often more effective and sustainable. External actors can play a supportive role, providing resources, expertise, and facilitation, but the primary responsibility for peace must lie with those directly affected by the conflict.

In conclusion, the patterns of conflict have changed, and our peacemaking strategies must change with them. This requires a nuanced understanding of the political dynamics driving violence and a willingness to adapt our approaches to meet the unique challenges of each conflict. While the task is daunting, it is not insurmountable. With innovative thinking and a commitment to addressing the root causes of violence, we can develop more effective strategies for promoting peace in our increasingly complex world.

Clionadh Raleigh is President and CEO, ACLED

By Aisha Khurram

It is easy to succumb to hopelessness regarding peace, especially when confronted with headlines about Afghanistan, the failed peace process, and the return of the Taliban to power. These events might suggest that peace is a lost cause in the country. However, the question isn’t whether peacemaking is still a priority—it’s a necessity in Afghanistan today.

Generations of Afghans have endured conflict and war. My grandmother survived the Cold War, raising my mother under Soviet bombs. My mother was forced to flee during the first Taliban rule in the 1990s, and I fled during their second rule just two and a half years ago. That makes three generations in my family alone experiencing war and displacement. My generation inherited this conflict; we didn’t start it, yet we became the machinery for leaders on both sides.

Four years ago, I represented Afghan youth at the United Nations Security Council, coinciding with the start of the Afghan peace process after four decades of war. Historically, we were passive receivers of agendas, fuelling wars led by politicians who never bore the consequences. We decided to claim our future, demanding not just a seat at the table but the right to end a war that wasn’t ours and to define our future on our own terms. We saw movements where young people spoke up for themselves, demanding an end to the war and attempting to integrate with young Taliban members to initiate grassroots peace processes.

However, the international community and negotiating parties treated the peace process as a mere project. Our voices were heard but not listened to. Politicians ignored our fears, leaving another disaster for my generation to deal with. After 20 years, the Taliban are back, and Afghanistan is globally isolated. It is the only country where girls are banned from education, unfolding a gender apartheid before our eyes. The lack of education access, not just for girls but for many boys due to poverty and Taliban restrictions, can turn Afghanistan into a serious threat to regional and global peace and security.

Four years ago, during the peace process, Europe and the US were involved. They not only dropped the ball but kicked it away, abandoning the democratic values they preached to Afghans. This failure is evident today as Afghanistan faces an unprecedented humanitarian crisis. The education crisis is just the tip of the iceberg, with the country grappling with severe humanitarian needs amidst global indifference due to emerging crises elsewhere, like Sudan, Myanmar, Ukraine, and Palestine.

Despite the challenges, resilience and courage emerged among young Afghans, driven by necessity rather than glorification. Even during the Republic, suicide bombings were our daily reality. My university and school were attacked, yet we persisted. In 2020, terrorists attacked my university, killing 22 students. A week later, we returned to the same classrooms, painted over the bloodstains, and continued our exams, embodying the hope for peace through education. This resilience highlights the crucial link between education and peace. Ignoring the necessity for peace amidst Afghanistan’s humanitarian crisis, prioritising food and water over education, risks a catastrophe that could take decades to reverse.

To hold governments and politicians accountable, we must leverage the growing dynamic, particularly in Europe, where the Israeli-Palestinian crisis has exposed the gap in peace perspectives between older and younger generations. Young people, regardless of religion, have united in protests, demanding an end to war and true peace. This is not just a series of protests but a global movement of young people demanding structural changes to end atrocities and violence. Until leaders take decisions with empathy, justice, and a commitment to human rights, the generational gap will widen, and cries for change will grow louder.

Regarding opening dialogue with the Taliban, it’s a complex question. Engaging with the government is necessary to support the population, help women, and develop projects. Four years ago, dialogue was opened with the Taliban when US national interests were at stake. Today, despite Afghan women being deprived of basic rights and people dying from impoverishment, there’s hesitation to explore political negotiations. While international monetary sanctions are important and should continue, we must also consider political engagement to pressure the Taliban.

Political negotiation could address the root causes of Afghanistan’s crisis, but we must also support underground movements of students and young women dedicated to democracy and freedom. Instead of waiting for a political solution, we can empower those committed to the cause of democracy and freedom, ensuring that their efforts contribute to a brighter future for Afghanistan.

Aisha Khurram is former Afghan youth representative to the UN 2019 and the director of E-learning initiative in Afghanistan

By Anna Popsui

In the context of the ongoing war in Ukraine, we witness a society deeply committed to democracy, European values, and gender equality. Despite the challenges posed by full-scale invasion, Ukraine is making strides toward democratic governance. Numerous bills and laws have been passed to enhance women’s involvement in negotiations, mediation, and various dialogues, including Track One and Track Two talks.

Ukraine’s youth stand at a critical crossroads. Traditionally seen as drivers of progress, young Ukrainians now face the grim reality of having to defend their nation. Instead of pursuing higher education, internships, and career opportunities, many are compelled to take up arms to protect European values and democracy from authoritarianism and unlawful occupation at the frontline.

Despite these dire circumstances, Ukrainian youth remain remarkably active and resilient. Many have initiated various projects and movements to bridge generational gaps and engage in direct dialogue with high-ranking officials. For instance, during my undergraduate studies, I organised discussions with ambassadors and consuls to voice the youth’s perspectives. Furthermore, I founded the Young Leaders Peacebuilders, an organisation aimed at educating young women and girls about the Women, Peace, and Security (WPS) agenda. This initiative underscores the importance of women asserting their presence in male-dominated spaces and contributing to peacebuilding efforts.

The reality of war is omnipresent for Ukrainian youth. Instead of enjoying the carefree days of youth, they confront the harshness of conflict in their families, in non-government controlled territories, and on the frontlines. In Brussels, a European city symbolising unity, I have encountered Ukrainian ex-combatants seeking rehabilitation. Despite significant investments, the needs are immense and ongoing. Since the conflict began in 2014, reintegrating ex-combatants has been fraught with challenges, particularly concerning gender-based violence (GBV) and domestic violence. However, Ukraine is striving to provide necessary rehabilitation facilities and opportunities for these individuals.

Addressing the question of national identity, Ukraine’s identity is dual-faceted. On one hand, it stands in opposition to Russian aggression. On the other, it aligns with European Union values. Since 2013, when students in Kyiv were targeted for their pro-European stance, Ukrainians have demonstrated a strong commitment to European integration. Similarly, in Georgia, youth are also advocating for European Union membership, opposing Russian influence, and showcasing a shared aspiration for democratic values.

Despite Russia’s attempts to subjugate Ukraine, the national identity is thriving. Cultural diplomacy and soft power play crucial roles in demonstrating Ukraine’s rich heritage and resilience. Even as we resist Russian aggression, we have much to offer the world, showcasing our cultural and historical depth.

Achieving peace during an active war is incredibly challenging. While I hope for peace and ceasefire, the reality is that missiles still target schools, universities, and civilian infrastructure. The current existential crisis demands immediate defence, but in the future, dialogue and peacemaking will be essential. The youth, having borne the brunt of the war, will likely play a pivotal role in bridging gaps and fostering reconciliation.

The ultimate goal is peace, the return of occupied territories, and the liberation of all Ukrainians held captive or displaced. During the Covid-19 pandemic in 2020, Ukraine had over 150,000 civil society organisations. By 2023, this number had risen to 270,000, reflecting a robust civil society dedicated to peace through humanitarian aid, education, and support to the defence of the country.

Ukrainian youth aspire for peace, democracy, and alignment with European values. They long for the day when the skies are safe, and civilian planes fly freely, symbolising a return to normalcy and hope. Despite the ongoing war, the spirit of Ukrainian youth remains unbroken, continually striving for a brighter, peaceful future.

Anna Popsui is Ukrainian women rights activist, Communications Specialist, Participant of the Women’s Peace Leadership Programme, OSCE

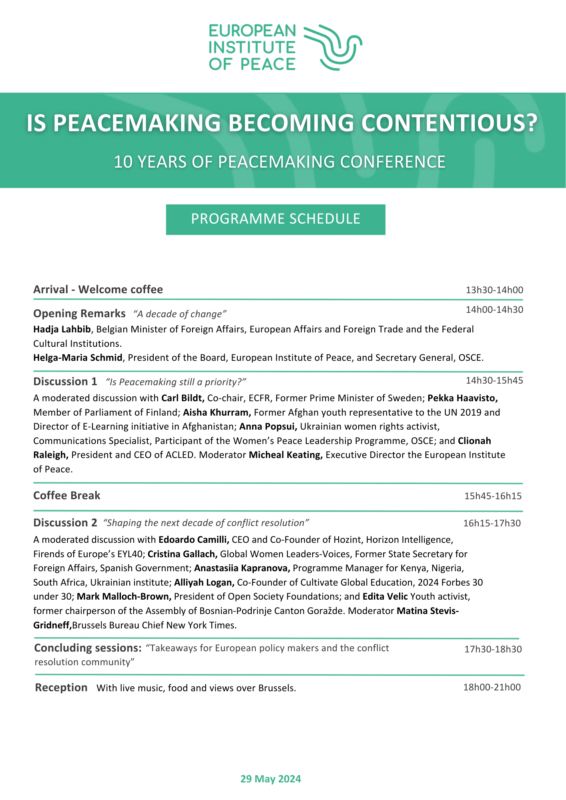

We find ourselves in an era characterised by new forms of warfare, violence and complex, interconnected armed conflicts. These are fuelled by myriad factors, from geopolitical tensions to climate change, socio-economic disparities to digital polarisation.

The skills and capacities associated with peace mediation are needed more than ever – yet they are at risk of being sidelined in the increasingly erratic world of global policy approaches to preventing and resolving armed conflict.

Official support for peaceful conflict resolution is on the decline, weakening global efforts to mitigate conflict-related suffering. The United Nations and other bodies established to save people from the scourge of war and affirm human dignity everywhere are struggling to fulfil their founding purpose. But the space for dialogue and conflict resolution has never been more urgently needed.

Mediators can play an indispensable role in facilitating dialogue and negotiation processes that can lead to sustainable solutions. They create channels of communication, bridge divides, cultivate trust, and work with conflicting parties to find common ground, thereby reducing the devastating human and economic toll of conflicts.

Peace mediation not only helps prevent further violence and suffering but can contribute to security and stability. In a world facing mounting challenges such as ecological collapse and rising temperatures, resource scarcity, terrorism and armed criminal networks, health and pandemic threats, the ability to identify common interests and resolve conflicts peacefully is a linchpin for achieving collective goals, fostering cooperation, and preserving the well-being of nations and their populations.

We live in a world where countries still take up arms against their neighbours, invade their lands, kill their citizens, and cause destruction without respect for international law, or human dignity. In this dark and grim context, fostering dialogue and supporting nonviolent conflict resolution is crucial and even urgent. These are the only true paths to peace, freedom and lasting security. And that’s why the Institute’s initiatives in conflict regions, along with various mediation initiatives, remains essential and requires significant effort in networking, human resources, and funding. Together, I’m sure we can make a real difference politically in governance, and financially and budget planning.

– Hadja Labib, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belgium

When, in February 2014, the Institute’s statutes were signed, a long-held ambition was realised: to create Europe’s own peace institute; one that acts independently to resolve conflict where official actors cannot, for the benefit both of Europeans and, crucially, of those worst affected by violence. We have been on a journey for the last decade towards making this ambitious project a reality.

From a modest staff and budget, the Institute has become a global network of over 150 advisors and experts supported by 50 full-time personnel based in Brussels. It now has a wide range of partnerships with actors dedicated to conflict prevention and resolution, both official and independent, local and international.

We work with the most experienced practitioners, including Nobel prize laureates, activists, officials from multilateral organisations, national and community leaders and others that can help influence just and sustainable outcomes. Today, the Institute is a recognised partner in the struggle for peace from Kosovo to Yemen, from Somalia to Venezuela, from Syria to Ukraine.

The European Institute of Peace has grown from being a handful of people back in 2014, to an organisation with 50 full time personnel in Brussels and over 150 advisors and associates. Many of whom are also present today, and who I would like to pay tribute to, including individuals with very specialist skills, very senior people with very senior experience, including as mediators, ministers, and managers. Today, the Institute is working in about 20 countries, engaging with parties to conflict, building backchannels, facilitating dialogues including track 1 and track 2, exploring new ways of bringing adversaries together, and catalysing initiatives that are designed to prevent violence and increase the agency of those most affected or at risk of conflict.

-Helga Schmid, Secretary General of OSCE and President of the Institute’s Board of Governors

We are engaged with individuals and groups on the front lines of armed conflict to hear and amplify their concerns and connect them with those that can make a difference. We reach people and places that official actors often cannot or will not, complementing and supporting the work of local conflict resolution actors. We are creative in designing and supporting dialogue, negotiations and peace processes, ensuring that the interests of people directly affected by violent conflict are front and centre.

Investing in peace mediation is a pragmatic way to address the complex challenges of our time, build relationships and contribute to strategies for achieving security and to help build a more peaceful world. However, mediators and conflict resolution practitioners are facing strong headwinds, operating in a rapidly changing political environment in which short term and military approaches to security are prioritised.

At the same time, there is a growing gap between the younger generation and government policy makers on how global challenges to peace are prioritised and addressed. Young people are disproportionally affected by insecurity and escalating conflict, yet most feel excluded from policies and decisions that will shape their future in decisive ways.

The voices of the young generation are increasingly politicised and loud when it comes to security and peace initiatives, both in countries affected by conflict and in protests and online discourse in the West. There is a pressing need and opportunity to address the gap between them and current decision and policy makers.

Young people, from Christians, to Jews to Muslims, they took to the streets united, asking for an end to the war and a true path to the peace. This is not just a couple of protests happening in Europe, for real change and real action to end atrocities and violence and war. It is a global movement of young people shaping and asking and demanding their leaders to change the structures that are creating these atrocities. Until the leaders and politicians, the Western world and also in the Global South […] take decisions and policies with empathy, with justice and commitment to human rights this generational gap will grow wider, and the cries for change from young people will be louder than ever before.

– Aisha Khurram, youth activist, Afghanistan

The bravery and resilience of young people in conflict zones underscores their role and potential as agents of change. Their vested interest in peace and security is driven by aspirations for a better future and the dire consequences they face if violence spreads and armed conflicts persist. This demographic, increasingly connected and tech-savy, harnesses digital platforms to mobilise, advocate, and innovate for peace.

We have seen young people being absolute catalysts and drivers of disruptive change in other parts of public life like environmental causes, we see them raising their voices in theatres of war and in campuses far away from that. It makes some of the older generations that hold the infrastructure of peacemaking and conflict resolution uneasy to see that – to see that force. We see them utilising new means of communicating and advancing and growing their voice, means that are unfamiliar perhaps to the people who govern the existing peacemaking and conflict resolution system.

-Martina Stevis Gridneff, Brussels Bureau Chief, The New York Times

Social media, online campaigns, and digital dialogues facilitate their involvement in peace processes, from grassroots movements to international fora. At the same time, the online space is fertile ground for hate speech, incitement and dehumanisation of ‘the other’, contributing to further polarisation and real world violence.

The perspective of young people is crucial to address these threats, as they bring fresh ideas and a sense of urgency to the peacebuilding table. The participation of young people in dialogue and peace initiatives is increasingly recognised as essential by global organisations and policymakers.

It is important for older generations to not only allow young people in the rooms, but hire young people, listen to young people and hear them not just taking notes, but making effective change. Give a young person a chance. I think that’s very important. And it’s even more important for young girls to see that messaging, see those investments in themselves in mentorship and an education, because it’s just such a crucial thing to not allow young girls to fall through the cracks.

– Alliyah Logan, education advocate and consultant at UNICEF, United States

As both victims and crucial stakeholders in the fight for peace, youth participation in policy discussions and practical initiatives is indispensable. Their involvement and common interest in a safer world can mitigate the worst impacts of violent conflicts but also lay the foundation for sustained global peace and security. Youth empowerment should be a priority for the international community.

This was the primary reason behind our decision to dedicate the 10th Anniversary of the European Institute for Peace to intergenerational dialogue on the future of peacemaking and bring young leaders from various contexts to the table with decision makers from governments and multilateral institutions.

This dialogue sought to explore how can we all as a global community, but Europe in particular, address global challenges that are crucial to peace, such as the erosion of political support for non-violent conflict resolution, the militarisation of responses to insecurity, failure to address the impact of climate change as a driver of crises, and the impact of social media on public discourse around conflict and peace.

Echoing the critical point emphasised by Finnish President Alexander Stubb in his video address to mark the occasion, “if you do not talk about peace, you cannot achieve it.”

Our aim was to catalyse a constructive discussion on what can be done to expand the space for dialogue and conflict resolution in a world marked by increasing violence and declining political support for peace initiatives. Our conference was not just an event but the beginning of an ongoing intergenerational dialogue which seeks to spark comprehensive discussions on the critical issue of global peace in a world marked by diverse challenges.

We clearly need to reimagine political leadership for peace. Our hope is that the conversations we initiated during the celebration of our 10th anniversary contributed to this in a meaningful way.

Michael Keating, Executive Director at the European Institute of Peace

The European Institute of Peace held a preliminary dialogue among several southern Yemeni political organisations between 1–3 June 2024 in the Dead Sea, in the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. Representatives of the following organisations participated in the dialogue:

- The Supreme Council of the Revolutionary Hirak

- The Participatory Southern Hirak to the National Dialogue Conference

- Revival (Nahdha) Movement for Peaceful Change

- Hadhramaut Inclusive Conference

- Southern National Coalition

- United Alliance of the People of Shabwa

- Hadhramaut National Council

- Shabwa National General Council

- Southern Women for Peace Group

Participants agreed on the rules and principles of the dialogue process and reviewed the political situation in the southern region and in Yemen in general. They discussed the relationship between the governorates and various state institutions, ways to rebuild and empower institutions in Yemen, and political representation of the southern Yemeni organisations. The dialogue also discussed proposals on involving other political forces in its workings, and the topics that will be discussed in upcoming sessions.

The participants agreed on the need to resolve all disputes in southern Yemen through negotiation, dialogue, and rejection of violence, with the need to respect all rights and freedoms guaranteed in international conventions.

A meeting was held between the participants and the Ambassadors of the European Union, the United Kingdom, Germany, and the Netherlands to Yemen, as well as a meeting with the Deputy Special Envoy of the United Nations in Yemen to exchange views on developments in the situation in the country.

The participants expressed their thanks and appreciation to the European Institute for Peace for the facilitation of this dialogue, which led to a convergence of views among them.

عملية الحوار في جنوب اليمن

عقد المعهد الاوروبي للسلام جولة تمهيدية للحوار بين العديد من القوى السياسية في جنوب اليمن في الفترة من 1-3 يونيو 2024 في البحر الميت في المملكة الاردنية الهاشمية، ولقد شارك في الحوار ممثلين عن الجهات التالية:

.المجلس الاعلى للحراك الثوري-

.الحراك الجنوبي المشارك في مؤتمر الحوار-

.حركة النهضة للتغيير السلمي-

.مؤتمر حضرموت الجامع-

.الائتلاف الوطني الجنوبي-

.التحالف الموحد لأبناء شبوة-

.مجلس حضرموت الوطني-

.مجلس شبوة الوطني العام-

.جنوبيات من اجل السلام-

اتفق المشاركون على الاسس والمبادئ المنظمة للحوار وقاموا باستعراض الوضع السياسي في الجنوب وفي اليمن بشكل عام، وناقشوا العلاقة بين المحافظات ومختلف مؤسسات الدولة، وسبل اعادة بناء المؤسسات في اليمن والتمثيل السياسي لمكونات الجنوب بما في ذلك التمكين في مؤسسات الدولة، كما ناقش الحوار بعض المقترحات حول إشراك قوى سياسة اخرى في اعماله، والموضوعات التي سيتم مناقشتها في دورات الحوار القادمة

اتفق المشاركون على ضرورة حل كافة الخلافات في الجنوب من خلال التفاوض والحوار ونبذ العنف، مع ضرورة احترام كافة الحقوق والحريات المكفولة وفقاً للمواثيق الدولية

عقد لقاء للمشاركين على هامش الحوار مع سفراء الاتحاد الاوروبي والمانيا وهولندا وبريطانيا لدى اليمن وكذلك لقاء مع نائب ممثل الامم المتحدة في اليمن من اجل تبادل الآراء حول تطورات الاوضاع في الجنوب وفي اليمن بشكل عام

وجه المشاركون كل الشكر والتقدير لإدارة المعهد الأوروبي للسلام على حسن إدارة وتيسير هذا الحوار الذي افضى إلى تقارب وجهات نظر المتحاورين

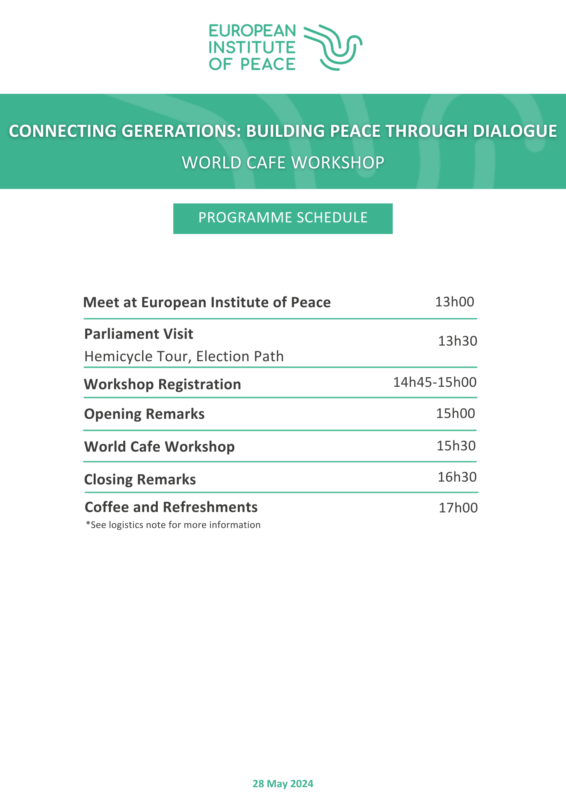

The European Institute of Peace partnered with the European Parliament to host a World Café Workshop for young political leaders and activists on 28 May as part of a series of events to mark the Institute’s 10-year anniversary. Over 40 young political leaders and activists from across the globe came together at the European Parliament’s Infohub to take stock of the current state of peacemaking and look at the decade ahead.

The workshop was attended by individuals from the Parliament’s Young Political Leaders Alumni network as well as individuals from various other networks such as Forbes, Friends of Europe, the Institute’s staff and other young leaders working in the fields of conflict resolution and peacemaking. Participants joined from the Western Balkans, Afghanistan, Iraq, Ukraine, the United States, and all over Europe to share and contribute their perspectives and experiences to the events discussion.

Since the United Nations Security Council Resolution 2250 on Youth, Peace and Security in 2015, the role young people have in peacemaking efforts has gained recognition in both public and private policy spheres. However, implementation gaps still persist despite recent reports showing that women, youth and children are bearing the brunt of conflict. In the 900 negotiated peace agreements signed globally in the last couple of decades, the voices of young people have been largely absent, according to the Youth Inclusive Guide to Peace Mediation.

The workshop emphasised the need for intergenerational dialogue in peacemaking efforts and aimed to highlight inclusive and innovative approaches to non-violent conflict resolution. Participants shared their experiences and ways they have been affected by conflict and contributed to peacemaking efforts. The workshop served as a forum for dialogue and networking ahead of an intergenerational event on 29 May in which several young leaders participated.

The format of the workshop followed a World Café, where participants were divided into separate tables that focused on four individual questions pertaining to the following topics; To empower youth and bridging generational gaps in peace efforts; To find new more inclusive and localised paths to peaceful resolution of conflict; To make the case for non-violent conflict resolution in a changing geopolitical environment; To navigate the impact of emerging technologies in conflict resolution. Exploring these prompts, each group was tasked with developing recommendations aimed at policymakers and peace practitioners on how to connect generations and build peace through dialogue.

A working group comprised of participants assigned to the four topics listed above has been established to build on the findings of the discussions. Among the points that emerged, the group emphasised the value of creating space for intergenerational dialogue through innovative, formal and informal formats to meet and expand upon the pillars of the Youth, Peace and Security agenda. They also reiterated the importance of tackling stereotypes and policy myths.

28-29 May, 2024:

A series of events to mark the 10th anniversary of the European Institute of Peace to discuss the current challenges to peacemaking and where we go from here.

The European Institute of Peace was born ten years ago. The objective of its founders was to create a centre of excellence in mediation and conflict resolution. An independent body, the Institute serves as a resource for states, the EU and civil society. Its activities include engaging parties to conflict, supporting dialogue, and initiatives to strengthen the agency of those affected by armed conflict, taking risks for peace and doing things that official actors often cannot.

Our mission is more relevant than ever – for unfortunate reasons. The number of people killed in armed conflict, levels of physical and mental violence, and humanitarian needs, both acute and chronic, are going up. Many more people now live in ‘no war, no peace’ situations, living with uncertainty, caught up in long-running internationalized civil wars and unresolved disputes.

The pace of climate change, demographic shifts, threats to health and digitalisation have accelerated. Instead of propelling solidarity in the face of common threats, they have resulted in divisiveness and competition. At the same time, the authority of the United Nations and other bodies set up to address these challenges, to prevent and resolve wars has diminished.

Europeans are facing a new reality, whether as a parties to the war in Ukraine or as the political impact hits home of war in the Middle East and of long-running unresolved conflicts in its broader neighbourhood. States and powerbrokers are employing an ever wider variety of means, military, economic and informational, to assert their interests and delegitimize their adversaries. This is prompting a significant change of gears.

Europe has long prided itself for being a peace project, recognising that dialogue, diplomacy and mediation are not alternatives to defence and deterrence but are essential tools in the search for lasting peace and security. At best, there is a risk this may be forgotten as priority is given to military preparedness and economic securitisation, and that focus on the war in Ukraine will result in the deprioritisation of investment in conflict resolution elsewhere. At worst, dialogue with adversaries may become unacceptable, and peacemaking denigrated as irresponsible.

To mark our 10th anniversary, we will host a series of events to take stock of peacemaking, its direction of travel and challenges ahead for Europeans, not least for young people. Is the political space and support for dialogue shrinking? Is enough being done to support civil society including to engage young people? What needs to done to protect investment in peacemaking and mediation?

Contact: Paul Nolan, Public Affairs and Communications Officer: paul.nolan@eip.org

Participants

Executive Director, European Institute of Peace

President of the Board, European Institute of Peace

Minister of Foreign Affairs, European Affairs and Foreign Trade and the Federal Cultural Institutions

President and CEO, ACLED

Member of Parliament of Finland

Former Minister of Foreign Affairs of Spain and Visiting Professor, Georgetown University

Ambassador of Finland to the Federal Republic of Germany

President of the Open Society Foundations

Former Afghan youth representative to the UN 2019 and the director of E-learning initiative in Afghanistan

Ambassador (ret.)

EU Special Representative for the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue and other Western Balkan regional issues

Brussels bureau chief, The New York Times

Lawyer and Political Advocate

Head of the European Commission Service for Foreign Policy Instruments (FPI)

Ukrainian women rights activist, Communications Specialist, Participant of the Women’s Peace Leadership Programme, OSCE

Director for Engagement, Dialogue and Process Design and Deputy Executive Director at the European Institute of Peace

Senior Advisor European Institute of Peace and Former Minister of International Development of Norway

Executive Vice President, Crisis Group

Executive Director, Conciliation Resources

Director for Peace Practice and Innovation, European Institute of Peace

UN Under-Secretary-GeneralPersonal Envoy of the Secretary-General for Western Sahara and Former President of the Board of the European Institute of Peace

Senior Advisor European Institute of Peace and Former President of the Board, European Institute of Peace

Executive Director, Berghof Foundation

Former Director General (for Migration and Home Affairs (2020- 2023) and for Humanitarian Aid and Crisis management (2015-2019), European Commission

Youth activist, former chairperson of the Assembly of Bosnian-Podrinje Canton Goražde

Co-Chair, ECFR and former Prime Minister of Sweden

Member of the Parliament of Albania, Democratic Party

Former EU Special Representative for Human Rights

Senior Advisor, European Institute of Peace

Education Advocate, and Consultant at UNICEF

Secretary of the Board, Global Women Leaders- Voices

CEO and Co-Founder, Horizon Intelligence (Hozint) and Friends of Europe’s European Young Leader (EYL40)

Senior Advisor, European Institute of Peace

Programme Manager for Kenya, Nigeria, South Africa, Ukrainian Institute

Director of the Conflict Prevention Centre and Deputy Head of the OSCE Secretariat

Programme

Brussels, 28 May, 2024 – The European Institute of Peace marks its 10th anniversary on 28-29 May. It will use the opportunity to focus on the changing nature and reduced space for peacemaking, particularly from a European and youth perspective.

“The number of people killed in armed conflict, levels of physical and mental violence, acute and chronic humanitarian needs are rising,” said Michael Keating, the Executive Director of the European Institute of Peace.” Many more people now live in ‘no war, no peace’ situations, caught up in long-running internationalised civil wars and unresolved disputes. Peacemaking is both more complex and more needed than ever”.

The Institute was set up to be an independent centre of competence in conflict resolution, partnering with European states, the EU, civil society and the broader peacemaking community. Active in 20 or so countries on four continents, its work includes engaging parties to conflict, facilitating dialogue, supporting mediation, and initiatives that increase the agency of people most affected by conflict. It works with a wide range of partners to create conditions for peace and security.

“The Institute’s mission is more relevant than ever – for unfortunate reasons,” added Micheal Keating. “Threats to peace and security are multiplying. Diplomacy and dialogue are not alternatives to defence and deterrence but an essential part of the mix if political solutions are to be advanced in an increasingly polarised world”.

Two events are being organised to put the spotlight on peacemaking today. The first on Tuesday 28th May is among young people to share views on the biggest peace and security challenges ahead, and how they can play a greater role. On Wednesday 29th, young people and experienced policy makers that have served as foreign ministers, special envoys and mediators will gather to discuss how peacemaking is changing and why it is receiving less political and financial support.

This takes place less than two weeks before European elections and a few months before a new European Commission is appointed. Bandwidth and budgets are being absorbed by the imperative of responding to urgent security threats and supporting Ukraine and, more recently, to conflict in the Middle East, deprioritising attention to conflicts and crises elsewhere.

For more information about the events, please visit the Institute’s website.

Partners and participants:

Together with the European Parliament Young Political Leaders alumni network, Friends of Europe, Forbes, the Kofi Annan Foundation and other partners, we are bringing together young and experienced leaders, including: Hadja Lahbib, Minister of Foreign Affairs of Belgium; Aisha Khurram, Afghan activist and former representative of Afghan youth to the United Nations; Miroslav Lajčák, EUSR for the Belgrade-Pristina Dialogue and other Western Balkan regional issues; Carl Bildt, former Prime Minister of Sweden; Anna Popsui, Ukrainian activist and co-founder of the Young Peacebuilding Leaders network (OSCE); and many others from the fields of diplomacy, international relations, and conflict resolution.

For media inquiries, please contact:

Paul Nolan

Public Affairs and Communications Officer

European Institute of Peace