On 9–11 December 2025, the European Institue of Peace facilitated the fifth round of the Southern Dialogue Process in Yemen in Amman, Jordan. The participants discussed the political situation in Yemen and expressed their grave concerns regarding recent developments in Hadhramaut. They agreed a foundational document and statutes for the upcoming launch of “The Platform of Political Forces in Southern Yemen.” The participants issued the following statement and released an agreed document on Common Ground among Southern Political Components.

Final Statement of the Fifth Round of Dialogue, 9-11 December 2025

Translated from the original Arabic

- The European Institute of Peace facilitated the fifth round of dialogue between various political forces and components in southern Yemen in the Jordanian capital, Amman, December 9-11, 2025. Representatives from the following components participated in the dialogue: the Supreme Council of the Revolutionary Movement for the Liberation and Independence of the South (Hirak), Nahdha Movement for Peaceful Change, the Southern Movement participating in the National Dialogue Conference (NDC Hirak), the Hadhramaut Inclusive Conference, Southern Women for Peace Group, the United Alliance of the Sons of Shabwa, the Shabwa National General Council, and the Hadhramaut National Council. The Southern National Coalition and the Peaceful Sit-in Committee in Al-Mahra Governorate were unable to participate due to acceptable circumstances.

- The political forces and components reviewed the political, economic, and security conditions in the southern governorates, particularly Hadramawt, and Yemen in general, and the deteriorating security, living conditions, and basic services they are facing.

- The political forces and components also followed the rapidly evolving developments and events in Hadramawt, including the accompanying political, security, and military tensions and the serious repercussions on the political process and national partnership in the south. They expressed deep concern regarding these developments and stressed that the use of violence and military force is a clear departure from the norms and values upon which peaceful political dialogue is based.

- The political forces and components also welcomed the truce agreement signed between the Governor of Hadramawt and the head of the Hadramawt Tribal Alliance, which was guaranteed by the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and stressed the need for its full implementation, addressing the causes of tension, and restoring stability in a way that defuses tensions, preserves civil peace, and enables local authorities to carry out their duties in accordance with the law.

- The political forces and components held the Presidential Leadership Council fully responsible for the current situation, which resulted from the escalation of internal disputes and conflicting powers and interests. They demanded that the Council assume its responsibilities and implement what was stated in the Riyadh Agreement and in the subsequent declaration of the transfer of power, and ensure the principle of partnership and fair representation of the political forces in the south without exclusion or marginalization.

- The southern political forces and components affirmed that dialogue, respect for partnership, and implementation of agreed-upon commitments are the true foundations for building a stable political situation and protecting the southern governorates. They called on the countries sponsoring the political process and the international community to assume their responsibilities and move towards achieving the required progress on the path of the political process.

- The political forces and components continued their discussions on establishing a platform for political forces in southern Yemen and agreed on the founding document and bylaws of the platform. This platform will include political forces that embrace the vital Southern cause, the specificities of its governorates, and the aspirations of its people. It will work to promote dialogue, coordination, and the defence of their issues, rights, and future at the national, regional, and international levels, in accordance with principles and objectives that regulate the relationship between the political forces and parties concerned with developments in the South in particular and Yemen in general. They also discussed the steps required in the next phase to launch this platform as soon as possible.

- The political forces and components agreed on a paper – copied below – which includes the commonalities of the southern political forces participating in the dialogue, and addresses their common position towards the current situation, the necessity of political partnership, the references for a political solution, the resolution of the southern issue and the issues of the governorates, the representation of the south in the political process, the necessity of conducting a dialogue on ways to reform the legitimate authority, the position on militias and armed factions, and achieving transitional justice and reparation.

- The political forces and groups discussed ways to cooperate in addressing the current crisis facing the South in particular and Yemen in general. They agreed to continue these discussions to develop ideas and proposals for dealing with the crisis in a way that alleviates the burdens of daily life and the difficult conditions faced by citizens.

- The political forces and groups appreciated the important meeting they held with the European Union Ambassador to Yemen to exchange views on developments in Yemen in general and the South in particular.

Common Ground among Southern Political Factions Participating in the Dialogue Sponsored by the European Institute of Peace

Translated from the original Arabic

The most important commonalities agreed upon by the southern political components participating in the dialogue sponsored by the European Institute of Peace, which they see as fulfilling the interests of the Yemeni people in general and the South in particular.

- The stance on war and peace:

The belief that a political solution is the best way to end the conflict in Yemen, and that the continuation of the war threatens the future of society and deepens the humanitarian tragedy. - The future form of the state:

A federal democratic framework is the appropriate framework for the future at this stage. - The Southern Cause:

Emphasizing the importance of the Southern cause and establishing guarantees for its resolution within a national framework that prevents a recurrence of the severe damage inflicted on the political, economic, and social levels. The people of the South have the right to demand and exercise their right to self-determination through peaceful means and internationally recognized legal mechanisms. - Governorate Causes:

The governorates have the right to determine their political and economic future within the framework of what is agreed upon in this regard. - Political Solution Framework:

The outcomes of the National Dialogue represent one of the fundamental frameworks for a political settlement, while emphasizing the importance of opening a dialogue on any other frameworks considering recent developments. - Representation of the South:

The South is politically diverse, and its constituent groups reject any single political entity monopolizing its representation or making decisions on its behalf unilaterally. - Political Partnership:

Agreement on the necessity of achieving partnership in political decision-making and rejecting exclusion and marginalization. - The current legitimate authority:

The Presidential Leadership Council in Yemen has shown its inability to manage the current phase in accordance with its national responsibilities, and there is a need to conduct a dialogue on ways to reform it. - The stance on weapons:

• Rejection of militias and armed factions, and affirmation that the State alone must have a monopoly on the use of force. Therefore, there is an urgent need to end this negative phenomenon immediately.

• Emphasis that any political settlement must lead to a just and lasting peace, thereby dismantling all parallel state entities and all forms of armament outside the framework of state institutions. - Transitional justice and reparation:

The need to ensure transitional justice through accountability and reparation by all possible means, including political isolation (while keeping the discussion open about other aspects of justice required and the starting date of the period covered by the accountability process).

في الفترة من 9 إلى 11 ديسمبر 2025، يسّر المعهد الأوروبي للسلام الجولة الخامسة من عملية الحوار الجنوبي في اليمن، التي عُقدت في عمّان، الأردن. ناقش المشاركون الوضع السياسي في اليمن، وأعربوا عن قلقهم البالغ إزاء التطورات الأخيرة في حضرموت .و اتفقوا على الوثيقة التأسيسية والنظام الأساسي لإطلاق ”منصة القوى السياسية في جنوب اليمن“. أصدر المشاركون البيان التالي، ونشروا وثيقة متفقا عليها حول القواسم المشتركة بين المكونات السياسية الجنوبية.

البيان الختامي للجولة الخامسة، 9 إلى 11 ديسمبر

- عقد المعهد الأوروبي للسلام الجولة الخامسة للحوار بين العديد من القوى والمكونات السياسية في جنوب اليمن وذلك في العاصمة الأردنية عمان في الفترة 9-11 ديسمبر 2025، ولقد شارك في الحوار ممثلو عن المكونات التالية: المجلس الأعلى للحراك الثوري لتحرير واستقلال الجنوب- حزب حركة النهضة للتغيير السلمي- الحراك الجنوبي المشارك في مؤتمر الحوار الوطني- مؤتمر حضرموت الجامع- جنوبيات من أجل السلام- التحالف الموحد لأبناء شبوة- مجلس شبوة الوطني العام- مجلس حضرموت الوطني، ولم يتمكن الائتلاف الوطني الجنوبي ولجنة الاعتصام السلمي في محافظة المهرة من المشاركة لظروف مقبولة.

- قامت القوى والمكونات السياسية باستعراض الأوضاع السياسية والاقتصادية والأمنية التي تمر بها المحافظات الجنوبية وحضرموت بشكل خاص، واليمن بشكل عام، وما تواجهه من تردٍ في الأوضاع الأمنية والمعيشية والخدمات الأساسية.

- كما تابعت مجريات التطورات والأحداث المتسارعة في حضرموت وما رافقها من توتر سياسي وأمني وعسكري وانعكاسات خطيرة على مسار العملية السياسية والشراكة الوطنية في الجنوب، وأعربت عن بالغ القلق إزاء هذه التطورات، وأكدت أن استخدام العنف والقوة العسكرية يعد خروجًا بيّنًا عن الأعراف والقيم التي يقوم عليها الحوار السياسي السلمي.

- كما رحّبت باتفاق التهدئة الموقّع بين محافظ حضرموت ورئيس حلف قبائل حضرموت والذي ضمنته المملكة العربية السعودية، واكدت ضرورة التطبيق الكامل لبنوده ومعالجة أسباب التوتر واستعادة الاستقرار بما يضمن نزع فتيل التوتر والحفاظ على السلم الأهلي، وبما يمكن السلطات المحلية من ممارسة مهامها وفقا للقانون.

- وقد حملت القوى والمكونات السياسية مجلس القيادة الرئاسي كامل المسئولية عما وصلت اليه الأوضاع نتيجة تفاقم الخلافات الداخلية وتضارب الصلاحيات والمصالح وطالبت المجلس تحمل مسؤولياته وتنفيذ ماورد في اتفاق الرياض وإعلان نقل السلطة وضرورة تحقيق مبدأ الشراكة والتمثيل العادل للقوى السياسية في الجنوب دون إقصاء او تهميش.

- وأكدت القوى والمكوّنات السياسية الجنوبية أن الحوار، واحترام الشراكة، وتنفيذ الالتزامات المتفق عليها، هي الأسس الحقيقية لبناء وضع سياسي مستقر ولحماية محافظات الجنوب، ودعت الدول الراعية للعملية السياسية والمجتمع الدولي إلى تحمل مسؤولياته والتحرك نحو تحقيق التقدم المطلوب على مسار العملية السياسية.

- كما تابعت القوى والمكوّنات السياسية مناقشاتها حولَ إنشاء منصة القوى السياسية في جنوب اليمن، واتفقت على الوثيقة التأسيسية والنظام الأساسي للمنصة التي ستضم قوى سياسية تتبنى قضية الجنوب الحيوية وخصوصيات محافظاته وتطلعات أبنائها وتعمل على دفع الحوار والتنسيق والدفاع عن قضاياهم وحقوقهم ومستقبلهم على المستوى الوطني والاقليمي والدولي وفق مبادئ واهداف تنظم العلاقة فيما بين القوى السياسية والأطراف المعنية بتطورات الأوضاع في الجنوب بشكل خاص واليمن بشكل عام. كما ناقشت الخطوات المطلوبة في المرحلة القادمة لإطلاق هذه المنصة في أقرب فرصة ممكنة.

- اتفقت القوى والمكونات السياسية على الورقة المرفقة والتي تتضمن القواسم المشتركة للقوى السياسية الجنوبية المشاركة في الحوار حيث تعرضت لموقفها تجاه الأوضاع الحالية، وضرورة الشراكة السياسية، ومرجعيات الحل السياسي، وحل القضية الجنوبية وقضايا المحافظات، وتمثيل الجنوب في العملية السياسية، وضرورة اجراء حوار حول سبل اصلاح السلطة الشرعية، والموقف من المليشيات والفصائل المسلحة، وتحقيق العدالة الانتقالية وجبر الضرر.

- ناقشت القوى والمكونات السياسية سبل التعاون مع الأزمة الحالية التي تواجه الجنوب بشكل خاص واليمن بشكل عام واتفق على متابعة هذا النقاش لطرح الأفكار والاقتراحات للتعامل معها بما يؤدي الى تخفيف الأعباء المعيشية والظروف الصعبة التي يمر بها المواطنون.

ثمنت القوى والمكونات السياسية اللقاء المهم الذي جمعهم مع سفير الاتحاد الأوروبي لدى اليمن لتبادل الآراء حول تطورات الأوضاع في اليمن ب

القواسم المشتركة بين المكونات السياسية الجنوبية

المشاركة في الحوار الذي يرعاه المعهد الأوروبي للسلام

أهم القواسم المشتركة التي تتوافق بشأنها المكونات السياسية الجنوبية المشاركة في الحوار الذي يرعاه المعهد الأوروبي للسلام وتراها محققة لمصالح الشعب اليمني بشكل عام والجنوب بشكل خاص.

- الموقف من الحرب والسلام:

الإيمان بأن الحل السياسي هو السبيل الأمثل لإنهاء النزاع في اليمن، وأن استمرار الحرب يهدد مستقبل المجتمع ويعمق المأساة الإنسانية. - شكل الدولة المستقبلية:

ان الإطار الاتحادي الديمقراطي في المرحلة الحالية هو الإطار المناسب للمستقبل. - القضية الجنوبية:

التأكيد على أهمية القضية الجنوبية ووضع ضمانات معالجتها في إطار مسار وطني يمنع تكرار ما وقع من أضرار بالغة على المستويات السياسية والاقتصادية والاجتماعية، ويحق للشعب في الجنوب ان يطالب بممارسة حقه في تقرير مصيره من خلال الوسائل السلمية والاليات القانونية المعترف بها دولياً. - قضايا المحافظات:

للمحافظات الحق في تقرير مستقبلها السياسي والاقتصادي في إطار ما يتم التوافق عليه في هذا الشأن. - مرجعيات الحل السياسي:

أن مخرجات الحوار الوطني تمثل أحد المرجعيات الأساسية للتسوية السياسية مع أهمية فتح حوار حول أية مرجعيات أخرى في ظل ما شهدته الأوضاع من تطورات. - تمثيل الجنوب:

أن الجنوب متعدد سياسياً والمكونات الجنوبية ترفض احتكار أي مكون سياسي لتمثيله او اتخاذ القرارات نيابة عنه بشكل منفرد. - الشراكة السياسية:

الاتفاق على ضرورة تحقيق الشراكة في صنع القرار السياسي ورفض الإقصاء والتهميش. - السلطة الشرعية الحالية:

أظهر مجلس القيادة الرئاسي في اليمن عدم قدرته على إدارة المرحلة وفق ما تقتضيه مسئولياته الوطنية وهناك حاجه إلى إجراء حوار حول سبل إصلاحه. - الموقف من السلاح:

• رفض المليشيات والفصائل المسلحة والتأكيد على أن احتكار السلاح يجب أن يكون بيد الدولة فقط، ومن هذا المنطلق فان هناك ضرورة لإنهاء هذه الظاهرة السلبية بشكل فوري.

• التأكيد على أن أي تسوية سياسية يجب أن تفضي إلى سلام عادل ومستدام، تنتهي بموجبه كافة الكيانات الموازية للدولة، وأشكال التسلح خارج إطار مؤسساتها. - العدالة الانتقالية وجبر الضرر:

ضرورة إنفاذ العدالة الانتقالية من خلال المحاسبة وجبر الضرر بكل الوسائل الممكنة بما في ذلك العزل السياسي لمن يثبت إدانته (مع بقاء النقاش مفتوحاً حول جوانب العدالة المطلوبة الأخرى وتاريخ بدء الفترة التي تشملها عملية المحاسبة).

عُقد في نيروبي، كينيا، من 28 نوفمبر إلى 1 ديسمبر، الحوار الفني الثاني حول صنع السلام المناخي والبيئي في اليمن. واستند هذا الاجتماع إلى نجاح الاجتماعات الثنائية السابقة والحوار الفني الأول الذي عُقد في أغسطس 2025 في عمّان، والذي حقق تفاهمًا مشتركًا حول قضايا المياه، بما في ذلك دورها في سوء التكيف والنزاعات والصراعات. وخلال الحوار في نيروبي، بادر المشاركون إلى وضع رؤية مشتركة ومسودة خارطة طريق للتعاون لمعالجة ندرة المياه في اليمن.

كان هذا الاجتماع المشترك الثاني للمشاركين الفنيين والسياسيين للحكومة اليمنية والمجلس الانتقالي الجنوبي، والذي دعا إليه المعهد الأوروبي للسلام، في إطار عمل متفق عليه للحوار والتعاون البيئي. وتهدف هذه العملية إلى معالجة القضايا المتعلقة بالموارد الطبيعية والبيئة ومخاطر المناخ بشكل مشترك، دعماً لفوائد السلام في تحقيق الاستقرار والمصالحة وتعزيز القدرة على الصمود. وتضمن الحوار عروضاً تقديمية حول حوكمة وإدارة المياه على المستويين الوطني والمحلي، مما وفر فهماً دقيقاً أتاح إجراء مناقشات عملية تهدف إلى حل قضايا المياه الملحة بما يتماشى مع أولويات سياسات الجهات المعنية.

أجرى المشاركون مناقشات معمقة، وعززوا التفاهم المشترك حول تحديات المياه الأكثر إلحاحًا في اليمن وأثرها على المجتمعات المحلية. نوقشت خلال الحوار الفني الثاني مجالات العمل الاستراتيجية والحلول العملية على المدى القصير والمتوسط والطويل لتحسين إدارة موارد المياه، ودعم التوفير المستدام لخدمات المياه في المناطق الحضرية والريفية، وتحسين الإدارة البيئية، كل ذلك باتباع نهج يراعي ظروف النزاع ويدعم السلام.

على هامش جمعية الأمم المتحدة للبيئة، أتاحت العاصمة الكينية فرصةً ثمينة للمشاركين للقاء المنظمات الدولية المعنية بمواجهة مخاطر الأمن المناخي في منطقة القرن الأفريقي وشبه الجزيرة العربية. وفي زيارةٍ لمركز التنبؤ بالمناخ وتطبيقاته التابع للهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بالتنمية (IGAD)، اطلع المشاركون على امكانية أن تتطور المخاطر الناجمة عن تغير المناخ والتدهور البيئي إلى كوارث ونزاعات، وكيفية الوقاية منها من خلال الإنذار المبكر والاستجابة لهذه المخاطر من خلال برامج التأهب.

كدراسة حالة، قامت الهيئة الحكومية الدولية المعنية بالتنمية (IGAD) بتحليل إعصار تيج، الذي ضرب ساحل المهرة في أكتوبر/تشرين الأول 2023. كما زار المشاركون مستشار الأمن المناخي التابع لبرنامج الأمم المتحدة للبيئة في الصومال للتعرف على مشروع رائد في جوهر، الصومال، يهدف إلى بناء القدرة على الصمود في مواجهة تغير المناخ وتحسين الأمن المائي والغذائي من خلال نهج متكامل يجمع بين بناء السلام والعمل المناخي.

المياه كأساس للصراع والتعاون في اليمن

في اليمن، حيث يُقدَّر أن حوالي 17 مليون شخص – أي ما يقرب من نصف السكان – يعانون من انعدام الأمن المائي، تتفاقم ندرة المياه الفعلية بسبب آثار النزاع المسلح، الذي قوَّض قدرة المجتمعات والسلطات على مواجهة المخاطر البيئية. في هذا السياق، يمكن للمياه أن تُفاقم التوترات، ولكنها قد تُشكِّل أيضًا مدخلًا للتعاون وبناء الثقة والحوار. تسعى عملية الحوار والتعاون البيئي التابعة للمعهد إلى تحويل القضايا البيئية من مصدر للخلاف إلى فرص لدعم السلام والاستقرار من خلال جهود مشتركة لتعزيز القدرة على الصمود في وجه المخاطر المناخية والبيئية. وقد مثّل الحوار الفني الأول حول صنع السلام المناخي والبيئي في اليمن، الذي اختُتم في أغسطس/آب 2025، نقطة انطلاق لاستكشاف هذه الفرص.

حول المشروع

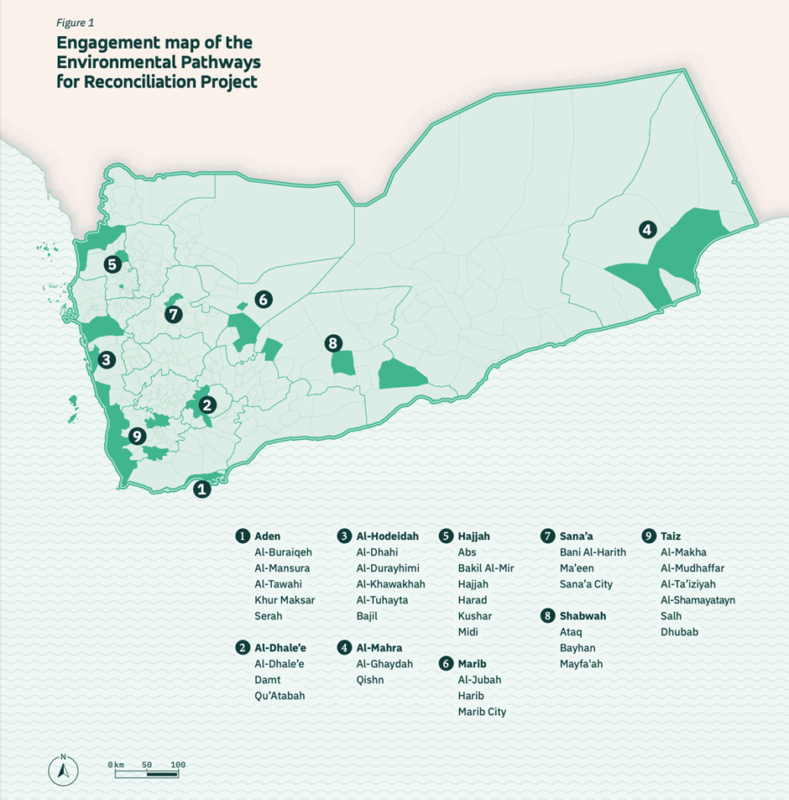

يهدف مشروع “المسارات البيئية للمصالحة” (EPfR) إلى المساهمة في تحقيق سلام مستدام في اليمن من خلال الحوار والتعاون البيئي. ومن خلال نهجه الشامل، يُعزز المشروع أصوات اليمنيين في المناقشات السياسية ومناقشات السلام، مستخدمًا القضايا البيئية كمدخلات وعناصر للسلام. يُنفذ مشروع EPfR من قِبل المعهد الأوروبي للسلام بدعم من وزارة الخارجية الألمانية الاتحادية، وهو جزء من ركيزة السلام “مقاومة المخاطر” التي تقودها منظمة أديلفي. يمكنكم الاطلاع على المزيد حول المشروع على الموقع الإلكتروني www.epfryemen.org .

From 28 November to 1 December, the Second Technical Dialogue on Climate and Environmental Peacemaking in Yemen took place in Nairobi, Kenya. The convening built on the success of previous bilateral meetings and the First Technical Dialogue facilitated in August 2025 in Amman, which achieved a joint understanding of water issues, including as a driver of maladaptation, disputes and conflict. During the dialogue in Nairobi, the delegates initiated the development of a common vision and draft roadmap for cooperation to address water scarcity in Yemen.

This was the second joint meeting of technical and political representatives of the Government of Yemen (GOY) and the Southern Transitional Council (STC) convened by the European Institute of Peace as part of an agreed framework of environmental dialogue and cooperation. The process seeks to jointly address issues related to natural resources, environment and climate risks in support of peace benefits on stabilisation, reconciliation, and enhanced resilience. The dialogue included presentations on water governance and management at the national and local levels, providing a nuanced understanding that enabled practical discussions aimed at solving pressing water issues in alignment with the policy priorities of the relevant authorities.

The delegates engaged in in-depth discussions and strengthened the joint understanding on the most pressing water challenges in Yemen and their impact on local communities. Concretely, during the Second Technical Dialogue, strategic areas of action and practical solutions were discussed at the short-, medium-, and long-term to better manage water resources, support the sustainable provision of water services in urban and rural areas, and improve environmental management, all with a conflict-sensitive and peace-positive approach.

On the sidelines of the United Nations Environmental Assembly, the Kenyan capital offered a great opportunity for the delegates to meet international organisations working on addressing climate security risks in the Horn of Africa region and the Arabian Peninsula. In a visit to IGAD’s Climate Prediction and Applications Centre, the delegates explored how hazards emerging from climate change and environmental degradation can develop into disaster and conflict risks, and how to prevent them through early warning and respond to these risks with preparedness programmes. As a case study, IGAD analysed Cyclone Tej, which hit the Yemeni coast of Al-Mahra in October 2023. The delegates also visited UNEP’s Climate Security Advisor to Somalia to learn about a flagship project in Jowhar, Somalia, building resilience to climate change and improving water and food security through an integrated approach combining peacebuilding with climate action.

Water as a ground for conflict and cooperation in Yemen

In Yemen, where about 17 million people – almost half of the population – are estimated to experience water insecurity, physical water scarcity is exacerbated by the effects of armed conflict, which has undermined the capacity of communities and authorities to address environmental risks. In this context, water can exacerbate tensions, but it can also serve as an entry point for cooperation, trust-building, and dialogue. The Institute’s Environmental Dialogue and Cooperation Process seeks to transform environmental issues from a source of contention into opportunities to support peace and stability through joint efforts to foster resilience to climate and environmental risks. The First Technical Dialogue on Climate and Environmental Peacemaking in Yemen, concluded in August 2025, has marked a starting point for exploring these opportunities.

About the project

The Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation (EPfR) project aims to contribute to sustainable peace in Yemen through environmental dialogue and cooperation. With its inclusive approach, the project amplifies Yemeni voices in political and peace discussions, using environmental issues as entry points and elements for peace. The EPfR project is implemented by the European Institute of Peace with support from the German Federal Foreign Office and is part of the Weathering Risk Peace Pillar led by adelphi. You can read more about the project at www.epfryemen.org.

In October our Programme Manager Miriam Østergaard Reifferscheidt and Senior Advisor Sophia Close shared evidence from our Breaking Barriers, Making Peace research with practitioners and policymakers at events hosted by UN Women, Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund, Women’s International League for Peace and Freedom (WILPF), PartnersGlobal and Alliance for Peacebuilding (AfP) in New York and Washington DC.

Our research across Myanmar, Ethiopia and Sudan reveals a sobering truth: 25 years after UNSCR 1325, the Women, Peace and Security agenda is ‘lost in plain sight’. We have robust normative frameworks but serious implementation gaps. We identified five persistent barriers limiting women’s meaningful participation in peacebuilding:

- Persistent patriarchal power and resistance – woven through international institutions and local structures. Many male-dominated organisations use ‘neutrality’ to avoid pushing for gender-inclusive outcomes.

- Threats to women’s security – Technology-facilitated GBV, conflict-related trauma and threats silence women’s leadership.

- Narrow, hierarchical and siloed efforts – Women remain mostly excluded from Track 1 peace processes despite 75% of peace processes involving women in informal peacebuilding.

- Incrementalism, exclusion and marginalisation – There’s a persistent belief that gradual inclusion is sufficient. This ignores the active systems maintaining exclusion.

- Underfunding and weak political investment – 99% of gender-related international aid fails to reach women’s rights organisations directly. Most receive funding for under 18 months, making sustained impact impossible.

These barriers aren’t accidental oversight. They are loaded with colonial history and oppressive gendered power dynamics, deeply embedded in global and local structures.

But we also found hope.

Our research assessed 12 promising practices to revive WPS implementation, including:

- Gender quotas: We call for mandated minimum 30% women in all preparatory talks, ceasefires and peace mediation processes. E.g. involving women in water project design increases effectiveness by up to seven times.

- Sub-national WPS Plans: Moving beyond traditional foreign affairs and defence silos to integrate climate resilience, economic security and health with culturally appropriate language.

- Radical reparative funding: Long-term, flexible core funding to feminist organisations, replacing colonial risk-management frameworks. Budget for physical, digital and psychosocial security as a participation right, not an extra.

- Building solidarity with men: Working with men in power to change discriminatory laws and social practices preventing women from participating in decision-making.

The climate-peace-security nexus is critical. From Myanmar’s monsoon disasters to Sudan’s desertification and Ethiopia’s droughts, climate shocks drive displacement, resource conflict and gendered insecurity. Women’s leadership in adaptation and resource governance must be recognised as a strategic security investment, not an add-on.

Resisting militarism is central to effective WPS implementation. Militarised values that elevate hierarchy, domination and force while sidelining cooperation, inclusion and care are inherently patriarchal. Without confronting militarism, new political formations simply reproduce patriarchal structures.

This isn’t only about justice: it’s about effectiveness. Our evidence shows meaningful women’s participation is a strategic imperative for sustainable peace.

Thanks to our partners for creating space for these useful conversations, and to all the women peacebuilders globally, and especially in Myanmar, Ethiopia and Sudan whose courage and insights shaped this research.

The full research is available here.

On 5 November 2025, UN Women, PAX and the European Institute of Peace jointly organised a high-level discussion on “Women, Peace and Security at a Crossroads: Funding, Localising and Reclaiming the Next 25 Years” at the European Parliament. Marking the 25th anniversary of UNSCR 1325 and the European Parliament Gender Equality Week, the event was co-hosted by MEP Abir Al-Sahlani (Renew), MEP Evin Incir (S&D), and MEP Hannah Neumann (The Greens) and brought together frontline activists from Iraq, Sudan, and Ukraine, Members of the European Parliament, EU Member States, UN representatives, and civil society leaders.

The message was clear: the next 25 years of WPS must be funded, localised, and reclaimed.

In the EU and Beyond

Evin Incir MEP warned of a growing backlash against the WPS agenda within the EU, stressing that meaningful progress requires cross-party cooperation and partnerships between institutions and civil society. She pointed to crises in Ukraine, Palestine, Sudan, and Syria, and reminded participants that violence against women persists both in conflict and in peace.

Abir Al-Sahlani MEP reflected on the changing nature of conflict, now more complex and societal, and cautioned that international law is being challenged as never before. She noted that many principles once taken for granted are now questioned, risking the erosion of commitments to gender equality and peace.

Marit Maij MEP added that women are not only victims of war, but also key to building peace: the face of conflict is often on women, but so is the face of the solution.

Sarah Douglas (Deputy Chief of Peace and Security at UN Women) described alarming trends: the proportion of women living in conflict zones has quadrupled, and conflict-related sexual violence has increased by 85%. At the same time, funding for women’s organisations has declined.

Miriam Reifferscheidt (Gender and Peacemaking Programme Manager at the European Institute of Peace) highlighted that defence spending is surging while resources for women and peace initiatives are shrinking. Donors often provide only short-term, activity-based projects, leaving women’s organisations weak and dependent.

Nada Murashkin (Policy Advisor Gender, Peace and Security at PAX) asked participants to think carefully about “whose peace” is being pursued, stressing that without accountability there is no real peace. WPS is a call to action, and policymakers are urged to translate commitments into concrete, justice-orientated measures.

Voices from the Ground

Reem Ghassan (Women Programme Manager at Peace and Freedom Organization (PFO), a human rights defender based in Erbil, Iraq, explained that the WPS agenda is often dismissed by political leaders, while armed groups and militias divert funding away from civil society. Cutting support, she warned, strengthens extremist mindsets and undermines stability.

Sudanese activist Niemat Ahmadi (President, Darfur Women Action Group, CEO and Founder, Unique22 Strategies) gave a powerful testimony of women facing starvation, slaughter, and violence, yet continuing to care for others and lead ceasefire efforts. She insisted that women earned their place and deserve to be at the negotiation table.

Ukrainian Expert in Gender Equality, Governance, and GBV, Yuliya Sporysh (PhD, Founder and Director, NGO GIRLS / ГО “Дівчата”) described the daily reality of war, where she checks in with her team each day to confirm they are alive. More than 75,000 women serve in the armed forces, yet 95 safe spaces for women have closed due to lack of funding. Gender-based violence has risen by 25% annually, while women-led organisations have almost no funding despite being on the frontlines.

Tonni Ann Brodber (Head of Secretariat, UN Women’s Peace and Humanitarian Fund) emphasized that their nine-year-old mechanism is the only UN mechanism that directly reaches civil society quickly and effectively. She cautioned that “one hand cannot clap,” stressing the need for collaboration and direct support for activists.

Armenian activist, Knarik Mkrtchyan warned against supporting women only in reactive positions, urging investment in prevention, early warning systems, and intersectional approaches to resilience.

Reclaiming the WPS Agenda: the Way Forward

1. Representation and Participation

- Guarantee women’s direct participation in peace processes and recognise women as key actors of peacebuilding not only victims.

- Apply gender quotas at all levels of peace processes and insist on a minimum 30 percent women representation to ensure a critical mass for real influence

- Uphold commitments to feminist agendas.

- Ensure reconstruction projects include women at the table (in bigger projects as well – not just in micro-initiatives such as bee-keeping and hairdressing).

- Move WPS policies beyond treating protection and participation as separate pillars by transforming the systems that make women’s participation dangerous.

2. Funding and Resources

- Provide long-term, flexible, equitable core funding to feminist organisations and movements.

- Move away from short-term, activity-based projects that keep organisations weak and dependent.

- Budget for physical, digital, and psychosocial security as a participation right; funding evacuation routes, digital encryption, mental health and trauma care, and legal defense for women leaders.

- Sustain funding and political backing for grassroots WPS actors to prevent the expansion of armed groups.

- Guarantee funding for survivors of sexual violence.

- Invest in existing civil society-led, feminist and rapid funding mechanisms and remove the risk-management away from grassroots organisations and individuals.

- Cover essential operational needs like office space and equipment.

3. Protection and Safety

- Adopt zero-tolerance policies against harassment and violence, online and offline.

- Provide self-care funds for staff working in high-stress environments

- Support frontline activists with rapid, accessible funds and protection windows.

- Recognize safety as the enabling condition of participation, not a reason for exclusion.

- Apply a focus of human security at all levels of financing including defence spending.

4. Accountability and Justice

- Adopt accountability as a fifth pillar of the WPS agenda, incorporating it into the EU-WPS action plan and into the CLIPS (Country Level Implementation Plans).

- Build accountability processes on inclusive consultations, systematic monitoring, independent audits, and enforcement of sanctions.

- Apply feminist analysis to financial shifts and set targets to redirect defence spending toward human security.

- Prioritize ceasefires and justice as critical, especially for relief and recovery.

5. Intersectionality, Masculinities, and Prevention

- Integrate a masculinities lens into foreign policy to counter militarized masculinities and engage men and boys as allies.

- Explore intersectional and decolonial approaches, creating safe and brave spaces for civil society partners.

- Mainstream human security, inclusivity, and intersectionality to ensure resilience during peacetime.

- Reinforce the preventive dimension of WPS, investing in women’s grassroots organisations and early warning systems and reporting mechanisms.

6. Bridging Global and Local Efforts

- Create bridges between actors to complement each other’s roles (including between UN and CSOs).

- Recognize WPS investment as prevention and a strategy for peace, not a strategy to react and respond to conflict.

- Focus donor support on independent civil society actors who share the vision of peacebuilding, rather than government-endorsed organisations.

- Ensure grassroots partnerships deliver the biggest and most sustainable impact.

Closing the event, moderator Sandra Melone (Chairwoman, Search for Common Ground Europe and Co-President, Elles du Sahel) captured the spirit of the discussion: despite the challenges, there remains hope and possibility galore. For the Europe that we want, the WPS agenda we want, progress must be accelerated, alliances built, and conversations made increasingly specific—including with unlikely partners.

On Tuesday 4 November, the European Institute of Peace co-hosted a high-level roundtable at the European Parliament, titled “Investing in Peace: The role of dialogue and conflict mediation in ensuring Europe’s security” with CMI – Martti Ahtisaari Peace Foundation, the Berghof Foundation, and Barry Andrews MEP.

The roundtable made the case for investing in peacemaking in the European Union’s Multiannual Financial Framework (MFF) 2028-34, which will be negotiated between the European Parliament, European Commission and Council of the EU for the next two years.

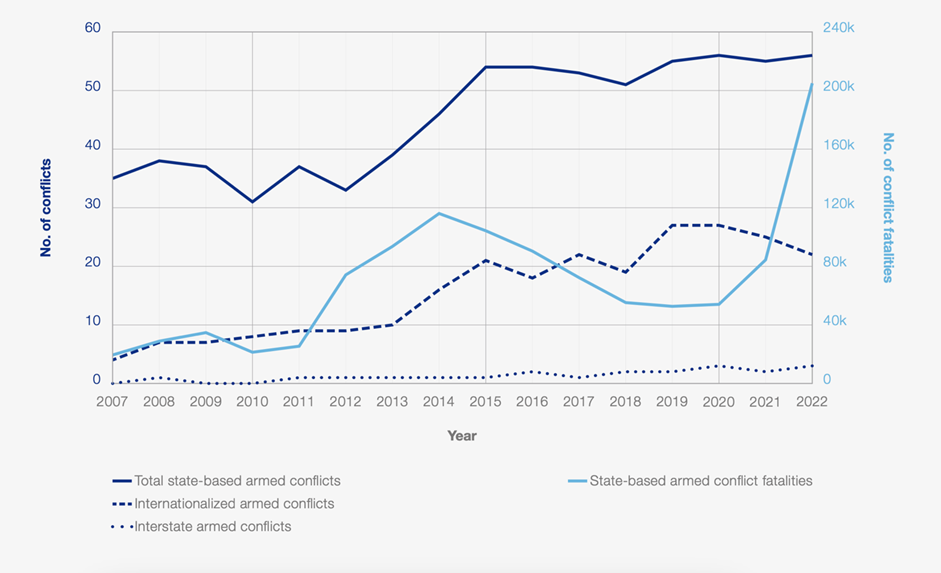

Eamon Gilmore, Senior Advisor at the Institute, set the scene by highlighting how, in a world with more conflict than at any time since the Second World War, there is a pressing need to make and sustain peace. This, however, requires significant investment of both time and resources: “If you want peace, you need to invest in it. Peace takes effort, investment, resources, and human power to make it happen, and needs far more support than it is getting.”

Throughout the discussion, speakers Barry Andrews MEP (Renew Europe, Ireland), Chris Coulter (Executive Director, Berghof Foundation), Hanna Klinge, (Deputy CEO, CMI) and Andrew Sherriff (Associate Director of Institutional Relations and Partnerships, ECDPM), brought up practical examples of their work in peacemaking, and highlighted a few key messages about European investment in peace:

- Peacemaking is cost-effective and sustainable. Military spending can be extremely costly, with a single fighter jet in the range of 70-110 million euros. Peace investment, on the other hand, is less expensive: a widely cited study by the World Bank states that for every dollar spent in conflict prevention 16 dollars can be saved in conflict costs: Investing in peacemaking is not just a moral imperative, but also a smart economic decision.

- Dialogue and mediation take time and resources but deliver real results. Peace processes require formal and informal networks, a clear understanding of local contexts and agendas, resources, and human powers. They also do not happen overnight: speakers highlighted how the Irish and Colombian peace processes went on for more than a decade. But peace is worth the wait, and the investment.

- The new MFF will need to balance defence spending with peace and development priorities. Military investment is very costly and cannot guarantee European security alone; it will need to be accompanied by investment in diplomacy, mediation, and conflict prevention that tackle root causes and support peacebuilders.

- This is a crucial moment for the EU to reaffirm its role as a leader in supporting sustainable peace around the world. As other global powers are investing less and less in sustainable peace Europe can and should step up to fill the gaps. This will strengthen the perception of EU’s external action worldwide and contribute to European security without compromising the EU’s values.

The roundtable also saw interventions from Michal Szczerba MEP (EPP, Poland, and advisor to the Institute’s Board), Hannah Neumann MEP (The Greens, Germany), Sebastian Tynkkynen MEP (ECR, Finland), and Sonya Reines-Djivanides (Executive Director, EPLO), who provided a wide range of perspectives on Europe’s global role and on investing in peacemaking in the next MFF.

At this week’s EU Community of Practice on Peace Mediation the Institute organised the session “Bringing Business In: The Case for Corporate Engagement in Peacemaking”.

The Institute’s Senior Advisors Eamon Gilmore and Urko Aiartza discussed the business community’s multifaceted role in contexts of conflict and peacemaking together with speakers Myriam Mendez-Montalvo, founder of the Colombian national dialogue platform Valiente es Dialogar (“Dare to Dialogue)and Sarah Cechvala, post-doctoral researcher at the University of Oslo focused on the role of the private sector in peace and conflict.

The discussion underscored the complexity and diversity of the business community and its multifaceted role in contexts of conflict and peacemaking.

Key reflections included:

- Diverse roles of business actors.The private sector is not monolithic and, while all companies aim for survival and profit, their incentives and impact vary widely. Businesses can be both allies in peace processes and, in some cases, conflict profiteers.

- Multiple pathways to peace. Business actors can contribute to peace not only through direct involvement in peace processes, but also by strengthening the social fabric, promoting inclusive growth, and creating conditions for stability. Good business is essential for peace, and, similarly, peace and a stable environment are in the business sector’s interest.

- The impact of business on fragile environments. Companies can create “peace pathways,” but the key issue is how they can shape and transform fragile environments. Their influence extends beyond traditional peacebuilding roles.

- The role of small businesses. Small businesses: Often deeply embedded in their communities, small enterprises tend to make strong socioeconomic contributions and show reluctance to engage in conflict. Given their social proximity and local impact, they can be seen as a hybrid between private sector and civil society actors, bridging the economic and the social dimensions of peacebuilding.

Throughout the conversation, different case studies where business actors contributed to peacemaking were also analysed, including:

- South Africa: The consultative business movement and the National Business Initiative (NBI) played a pivotal role in supporting dialogue and reform during the post-apartheid transition.

- Basque Country: Businesses avoided public roles due to security risks – which shows that engagement strategies are highly dependent on context. But they did work on developing and strengthening the social fabric.

- Colombia: Peace remains a polarising issue, even within the private sector. While there is no coordinated, national-level effort, localized initiatives, particularly in agriculture, have made meaningful contributions.

Finally, the discussion highlighted the importance of the “peace-positive” impact of business. Actions such as job creation, ethical investment, and community engagement may not fit traditional peacebuilding definitions, but are nonetheless crucial in creating the conditions for sustainable peace.

In August, the Institute’s Climate and Environmental Peacemaking Programme convened various parties from the relevant authorities within the Government of Yemen to jointly discuss the water situation in the country. The meeting took place in Amman and aimed to examine concrete challenges in specific governorates and cities, to find a common vision and identify potential solutions on how to address these issues from the water supply and demand sides. After four days of meetings, the delegates jointly developed a strategic list of practical solutions to address the country’s water issues. The group will reconvene at the end of 2025 to continue discussions.

Building on a series of unilateral meetings facilitated by the Institute, the Fourth Technical Meeting on Climate and Environmental Peacemaking in Yemen marked the first joint meeting of the relevant government parties, including the Southern Transitional Council (STC). The initiative is based on an agreed framework of environmental dialogue and cooperation, which recognises that jointly addressing natural resources, environment and climate risks can offer peace benefits on stabilisation, reconciliation, and enhanced resilience against both environmental and conflict risks.

The discussions helped to find common ground by recognising shared interests, values, and goals in a context of water scarcity. This mutual understanding included the need for updated and more accurate assessments of surface and groundwater availability, usage trends, and identification of the region’s most pressing water hotspots, especially where competition may lead to tensions and disputes.

Water, peace and conflict in Yemen

Yemen has long been struggling with water provision for agricultural, industrial, and household uses. With its semi-arid to arid climate, the country is naturally prone to physical water scarcity and largely dependent on non-renewable groundwater resources. After a decade of armed conflict, Yemen’s water situation has developed into a severe crisis, with about 17 million Yemenis lacking access to water for daily needs. Direct impacts of war, such as the destruction of water networks, have paired with financial challenges, a lack of capacity, and demographic growth, all of which have been exacerbated by the conflict. As the impacts of climate change, such as fluctuations in rainfall rates, are showing themselves more clearly, the issue of water scarcity is becoming ever-more pressing.

Not only does the water crisis have humanitarian implications, but it also affects social cohesion, fuels competition, and drives conflict. Already before the escalation of the war, water was identified as a significant factor contributing to tensions in Yemen. As the conflict continues and Yemen’s water resources are depleting, an integrated approach to peacemaking that recognises these connections is becoming indispensable. In this context, the Institute’s engagement seeks to leverage shared environmental concerns as a new avenue for peace, to transform environmental matters from a source of tension to an opportunity for joint action.

About the project

The Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation (EPfR) project aims to contribute to sustainable peace in Yemen through environmental dialogue and cooperation. With its bottom-up and inclusive approach, the project amplifies Yemeni voices in political and peace discussions, using environmental issues as entry points and elements for peace. The EPfR project is implemented by the European Institute of Peace with support from the German Federal Foreign Office and is part of the Weathering Risk Peace Pillar led by adelphi. You can read more about the project at www.epfryemen.org.

في مطلع أغسطس، عقد برنامج صنع السلام المناخي والبيئي التابع للمعهد الأوروبي للسلام اجتماعًا ضمّ جهات مختلفة من الجهات المعنية في الحكومة اليمنية لمناقشة الو ضع المائي في البلاد. عُقد الاجتماع في عمّان، وكان الهدف منه دراسة التحديات الملموسة في محافظات ومدن محددة، والتوصل إلى رؤية مشتركة وتحديد الحلول الممكنة لمعالجة هذه القضايا من حيث العرض والطلب على المياه. وبعد أربعة أيام من الاجتماعات، وضع المشاركون قائمة استراتيجية بالحلول العملية لمعالجة قضايا المياه في البلاد. وستجتمع المجموعة مجددًا في نهاية عام 2025 لمواصلة النقاش.

بناءً على سلسلة من الاجتماعات الأحادية التي يسّرها المعهد، مثّل الاجتماع الفني الرابع حول صنع السلام المناخي والبيئي في اليمن الاجتماع المشترك الأول للأطراف الحكومية المعنية، بما في ذلك المجلس الانتقالي الجنوبي. وتستند هذه المبادرة إلى إطار عمل متفق عليه للحوار والتعاون البيئي، يُقرّ بأن التصدي المشترك لمخاطر الموارد الطبيعية والبيئة والمناخ يُمكن أن يُحقق فوائد للسلام في تحقيق الاستقرار والمصالحة، وتعزيز القدرة على الصمود في وجه المخاطر البيئية ومخاطر الصراع.

ساهمت المناقشات في إيجاد أرضية مشتركة من خلال الإقرار بالمصالح والقيم والأهداف المشتركة في ظل ندرة المياه. وشمل هذا التفاهم المتبادل الحاجة إلى تقييمات محدثة وأكثر دقة لتوافر المياه السطحية والجوفية، واتجاهات استخدامها، وتحديد بؤر المياه الأكثر إلحاحًا في المنطقة، لا سيما حيث قد تؤدي المنافسة إلى توترات ونزاعات.

المياه والسلام والصراع في اليمن

يعاني اليمن منذ زمن طويل من نقص المياه للاستخدامات الزراعية والصناعية والمنزلية. فبفضل مناخه شبه الجاف إلى الجاف، يُصبح البلد بطبيعة الحال عُرضةً لندرة المياه، ويعتمد بشكل كبير على موارد المياه الجوفية غير المتجددة. وبعد عقد من الصراع المسلح، تفاقم الوضع المائي في اليمن إلى أزمة حادة، حيث يفتقر حوالي 17 مليون يمني إلى المياه لتلبية احتياجاتهم اليومية. وقد اقترنت الآثار المباشرة للحرب، مثل تدمير شبكات المياه، بالتحديات المالية، ونقص الإمكانيات، والنمو السكاني، وكلها تفاقمت بسبب الصراع. ومع تزايد وضوح آثار تغير المناخ، مثل تقلبات معدلات هطول الأمطار، أصبحت قضية ندرة المياه أكثر إلحاحًا من أي وقت مضى.

لا تقتصر أزمة المياه على الآثار الإنسانية فحسب، بل تؤثر أيضًا على التماسك الاجتماعي، وتؤجج التنافس، وتدفع الى الصراع. وحتى قبل تصاعد وتيرة الحرب، كان يُنظر إلى المياه كعامل رئيسي يُسهم في التوترات في اليمن. ومع استمرار الصراع ونضوب موارد المياه في اليمن، أصبح اتباع نهج متكامل لصنع السلام يُدرك هذه الروابط أمرًا لا غنى عنه. في هذا السياق، يسعى المعهد من خلال عمله إلى الاستفادة من الاهتمامات البيئية المشتركة كمسار جديد للسلام، وتحويل القضايا البيئية من مصدر للتوتر إلى فرصة للعمل المشترك.

نبذه عن المشروع

يهدف مشروع “المسارات البيئية للمصالحة” (EPfR) إلى المساهمة في تحقيق سلام مستدام في اليمن من خلال الحوار والتعاون البيئي. ومن خلال نهجه التصاعدي والشامل، يُعزز المشروع أصوات اليمنيين في المناقشات السياسية ومناقشات السلام، مستخدمًا القضايا البيئية كمدخل وعنصر للسلام. يُنفذ مشروع المسارات البيئية للمصالحة من قِبل المعهد الأوروبي للسلام بدعم من وزارة الخارجية الألمانية، وهو جزء من ركيزة السلام لمقاومة المخاطر بقيادة أديلفي. يمكنكم الاطلاع على المزيد عن المشروع على الموقع الإلكتروني www.epfryemen.org.

After 25 years of UN Security Council Resolution 1325, we stand at a critical crossroads. The Women, Peace and Security agenda – once a beacon of transformative possibility – faces multiple threats: political space for gender equality is narrowing, commitments and funding are eroding, and in many contexts, we are witnessing the agenda going into reverse.

Our new report, “Status Quo or Bold Adaptation? Reclaiming the Women, Peace and Security Agenda,” charts a path forward rooted in feminist principles: radical inclusivity and decolonial thinking.

Through extensive interviews, surveys and in-depth case studies in Ethiopia, Sudan and Myanmar, we identified five persistent barriers preventing women’s meaningful participation in conflict prevention and peace processes:

- Persistent patriarchal power and resistance

- Threats to women’s safety and ongoing trauma

- Narrow, hierarchical and siloed efforts

- Incrementalism, exclusion and marginalisation

- Inadequate financial and weak political investment

But this research goes beyond identifying the problems. We have analysed 12 promising practices that can work, distinguishing between well-meaning practices that fail and those grounded in feminist peace principles. The research revealed that many well-intentioned WPS efforts fail because they operate within existing limitations rather than transform the systems that create those limitations.

Our recommendations for practitioners to strengthen the WPS agenda from within call for:

- Men stepping up in solidarity

- Gender-responsive security and trauma-informed approaches

- Women, Peace and Security integrated across all government functions

- Meaningful gender quotas in all peace processes

- Radical reparative funding for feminist organisations

As we approach the 25th anniversary of UNSCR 1325, we have a choice: accept the status quo and watch the WPS agenda continue to erode, or embrace bold adaptation that matches the transformative vision women peacebuilders have been pushing for.

The evidence is clear. The solutions are available. The question now is whether we have the political will to implement them.

The time to act boldly is now.

This report exists thanks to the courage and wisdom of peacebuilders, especially those in Myanmar, Sudan and Ethiopia, who shared their lived experiences with us. Our recommendations reflect their shared knowledge. We are grateful for their contributions, and we extend our sincere appreciation to the German Federal Foreign for funding this critical research.

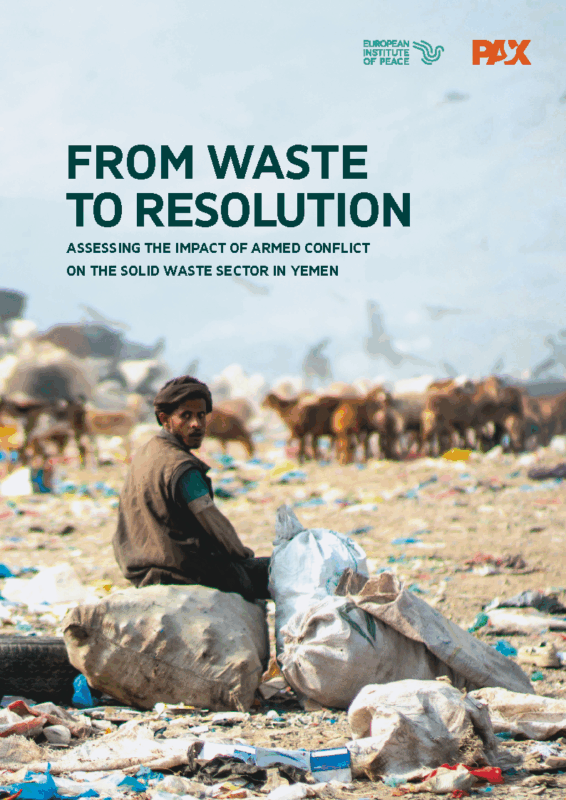

The European Institute of Peace and PAX are proud to announce our joint publication, “From waste to resolution: Assessing the impact of armed conflict on the solid waste sector in Yemen”, which provides insight into Yemen’s waste management crisis and its impact on the local environment, population, and society.

Throughout a decade of war, Yemen has been experiencing significant environmental degradation, both through direct impacts of armed conflict and indirectly through the decay of governance structures that could prevent and respond to environmental needs.

The conflict has eroded the capacity of public entities to protect crucial ecosystems, enact and implement relevant legislation, and provide essential services to Yemen’s population. When it comes to waste management, this has resulted in widespread illicit dumping, an uncontrolled expansion of solid waste, and a lack of adequate collection, disposal, and treatment facilities.

This report investigates Yemen’s waste crisis as a result of the armed conflict and reflects on ways to address it as a contribution to peacemaking, conflict prevention, and stabilisation. It identifies the main governance challenges in relation to effective waste management, including exponential demographic growth, lack of updated data, and weak institutional capacity. It analyses the environmental impact of Yemen’s solid waste crisis on air, water, and land, as well as its social and security implications, ranging from outbreaks of diseases to the degradation of agricultural land and an increase in competition for resources.

The report identifies three entry points to respond to the waste management crisis:

- Fostering collaboration and social cohesion: Strengthened coordination between various actors can offer co-benefits by improving solid waste management (SWM) services, while enhancing relationships between these stakeholders through joint decision-making or implementation. Collaboration, for instance on mapping needs, data sharing, or recycling initiatives, can be fostered between authorities and with the broader population alike, offering valuable opportunities for meaningful engagement of various groups. By involving communities in decision-making and implementation on SWM, authorities can garner popular support as a central pillar of lasting peace.

- Enhancing governance and building trust through technical cooperation: Technical subjects such as SWM offer opportunities for local and national authorities to strengthen their role and legitimacy in governance, hence improving the delivery of services and supporting public trust in institutions. At the same time, it can provide opportunities for dialogue, learning and knowledge-sharing across institutions and governorates to enhance the capacities of relevant SWM agencies, while contributing to increased coherence and trust between different institutions or parties.

- Strengthening livelihoods and unlocking economic opportunities: Investments and partnerships to improve SWM infrastructure can provide local economic opportunities through job creation and livelihood diversification, while providing revenue for municipalities and businesses. This way, investments in waste management infrastructure and enhanced waste governance can play a role in bolstering the local economy as a fundamental pillar of resilience and stability, especially if complemented with community-driven structures or solutions.

Based on these entry points, the report provides the following recommendations to provide guidance for local and national policymakers, donors, as well as international and multilateral organisations seeking to support peace and stability in Yemen.

- Addressing policy, legal and institutional gaps: Policymakers in Yemen are recommended to systematically review and update the legislative SWM framework, including the National SWM Strategy; strengthen institutional capacity of the CCIFs; and centralise collection and monitoring of waste data, all of which can contribute to improved waste management and environmental health.

- Mitigating environmental impacts of the waste crisis: Humanitarian and development organisations operating in Yemen are recommended to support expanded research on other dimensions of pollution and environmental degradation in the context of the conflict; enhance recycling and composting initiatives to depart from dumping; establish collection and disposal systems of hazardous waste; and expand waste-to-energy projects.

- Supporting resilience-building and preventing tensions: Local authorities and SWM entities are recommended to promote community-led approaches to waste management and engage in dialogue and peer learning to enhance coordination across the SWM sector.

This report is part of the Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation in Yemen project, implemented by the European Institute of Peace with support from the German Federal Foreign Office as part of the Weathering Risk Peace Pillar led by adelphi.

The full report is available here.

Join the European Institute of Peace and PAX for the online launch of our joint report “From waste to resolution: Assessing the impact of armed conflict on the solid waste sector in Yemen,” which provides insight into Yemen’s waste management crisis and its impact on public health, ecosystems, and long-term stability.

The webinar will present the findings from an extensive assessment of Yemen’s solid waste sector amid the conflict, drawing from geospatial mapping and policy analysis. It will explore the drivers and consequences of uncontrolled dumping and waste accumulation, as well as entry points to address them as a contribution to peacemaking, conflict prevention, and stabilisation.

The launch will take place in an online webinar on Wednesday, 10 September, from 15:00 to 16:30. The full report will be available online immediately after the event.

Speakers:

- Hisham Al-Omeisy, Senior Yemen Advisor, European Institute of Peace

- Elias Kharma, Research Analyst, European Institute of Peace

- Marie Schellens, Geospatial Analyst, PAX

- Wim Zwijnenburg, Project Leader Humanitarian Disarmament, PAX

Moderator:

- Alina Viehoff, Climate and Security Advisor, adelphi

This event is part of the Path to Ottawa series organised by EnPax ahead of the 4th International Conference on Environmental Peacebuilding, which will take place in June 2026 in Ottawa, Canada.

Este artículo también está disponible en inglés/This article is also available in English.

Durante décadas, Nariño ha sido uno de los territorios más violentos e inestables de Colombia. Su posición geoestratégica, fronteriza con Ecuador y con acceso directo al Pacífico, lo ha convertido en un corredor clave para el narcotráfico, la minería ilegal y otras economías ilícitas. El departamento cuenta actualmente con aproximadamente 65 000 hectáreas de coca, lo que supone alrededor del 26 % del total de cultivos del país.

Sin embargo, desde 2024, Nariño se ha convertido en uno de los pocos lugares donde la política de “Paz Total” de Colombia está dando resultados concretos. Dos grupos armados, Comuneros del Sur (antes ELN) y la Coordinadora Nacional Ejército Bolivariano (antes FARC), han entablado negociaciones con el Gobierno colombiano, han comenzado a entregar armas, han establecido zonas de ubicación temporal y han firmado acuerdos humanitarios que abarcan cuestiones como la sustitución de cultivos de coca, el reclutamiento de niños y el desminado. Como resultado, según datos de la Gobernación de Nariño, los homicidios disminuyeron un 84% entre 2023 y 2024, los casos de reclutamiento de niños y niñas se redujeron un 65% y los incidentes con minas terrestres disminuyeron un 99%.

Estos avances son el resultado de llevar los procesos de diálogo y negociación al ámbito territorial, lo que permite un enfoque más matizado y específico para cada contexto, combinado con el desarrollo de una estrategia de dividendos de paz por parte de la Gobernación de Nariño. Esta estrategia, centrada en iniciativas socioeconómicas y medioambientales, cuenta con el apoyo del Instituto Europeo para la Paz y permite tanto a los directamente involucrados en el proceso como a la población en general experimentar los beneficios tangibles de la paz. Los avances de Nariño tienen el potencial de remodelar la dinámica del conflicto en Colombia, especialmente en departamentos vecinos como el Cauca, y en toda América Latina a través de sus conexiones con Ecuador y el Pacífico, al desarticular las economías ilícitas y las redes criminales que operan mucho más allá de las fronteras administrativas y estatales.

En junio de 2025, el gobernador del departamento colombiano de Nariño, Luis Alfonso Escobar Jaramillo, visitó Bilbao, Vitoria y Bruselas con el apoyo del Instituto. La visita tenía como objetivo dar a conocer los innovadores esfuerzos de paz de Nariño. También se buscaba movilizar el apoyo internacional para una región cuya estabilidad y desarrollo son fundamentales para los esfuerzos de paz de Colombia y tienen importantes implicaciones para la seguridad en toda América Latina. Se organizaron comparecencias en los Parlamentos Vasco y Europeo, y se celebraron reuniones con el Gobierno Vasco y altos funcionarios de la Unión Europea (UE), entre los que se encontraban representantes del Servicio Europeo de Acción Exterior, el Servicio de Instrumentos de Política Exterior, la Dirección General de Asociaciones Internacionales y la Dirección General de Migración y Asuntos Internos, entre otros. Asimismo, se coorganizó una sesión de trabajo con organizaciones de la sociedad civil con sede en Bruselas activas en Colombia junto con la Embajada de Colombia en Bélgica.

La visita del gobernador a Europa puso de relieve el papel fundamental de los socios internacionales, en particular de la UE. La diplomacia europea puede ayudar a dar visibilidad al modelo de paz de Nariño y apoyarlo como iniciativa piloto para otros territorios fronterizos afectados por el conflicto. La cooperación financiera y técnica —a través de la iniciativa Global Gateway de la UE, la cooperación bilateral, las empresas público-privadas y socios estratégicos como el Instituto— será esencial para consolidar los dividendos de la paz, la transición de las economías ilícitas y el fortalecimiento de la resiliencia de las comunidades.

Durante más de dos décadas, la UE ha sido uno de los socios más comprometidos con la paz en Colombia, con una inversión de más de 500 millones de euros en apoyo político y financiero, sin contar las contribuciones de sus estados miembros. Su respaldo fue fundamental para garantizar el histórico acuerdo de paz de 2016 y avanzar en su implementación. Colombia es uno de los éxitos más notables de la UE en términos de resolución de conflictos y apoyo a la construcción de la paz. Hoy, con la Cumbre CELAC-UE de noviembre en el horizonte, es fundamental reafirmar que no es momento de dar un paso atrás. Colombia y las iniciativas de paz territorial como las de Nariño demuestran que un apoyo internacional sostenido y flexible proporciona seguridad, desarrollo y estabilidad, lo que beneficia no solo a las comunidades locales, sino también a toda la región y a la comunidad internacional en su conjunto.

This article is also available in Spanish/Este artículo también está disponible en español.

For decades, Nariño has been one of Colombia’s most violent and unstable territories. Its geostrategic position, bordering Ecuador and with direct access to the Pacific, has made it a key corridor for drug trafficking, illegal mining and other illicit economies. The department currently accounts for approximately 65,000 hectares of coca, which is about 26% of the country’s total crops.

However, since 2024, Nariño has become one of the few places where Colombia’s ‘Total Peace’ policy is producing concrete results. Two armed groups, Comuneros del Sur (formerly ELN) and the Coordinadora Nacional Ejército Bolivariano (formerly FARC), have entered negotiations with the Colombian Government, begun handing over weapons, established temporary encampment zones, and signed humanitarian agreements covering issues such as coca crop substitution, child recruitment and demining. As a result, according to data from the Governorate of Nariño, homicides decreased by 84% between 2023 and 2024, child recruitment cases dropped by 65%, and landmine incidents declined by 99%.

These breakthroughs are the result of taking the engagement and negotiation processes to the territorial level, allowing for a more nuanced and context-specific approach, combined with the development of a peace dividends strategy by the Governorate of Nariño. This strategy, centred on socioeconomic and environmental initiatives, is supported by the European Institute of Peace and enables both those directly involved in the process and the broader population to experience the tangible benefits of peace. Nariño’s progress has the potential to reshape conflict dynamics within Colombia, particularly in neighbouring departments like Cauca, and across Latin America through its connections with Ecuador and the Pacific, by disrupting the illicit economies and criminal networks that operate far beyond administrative and state boundaries.

In June 2025, the Governor of Colombia’s Nariño department, Luis Alfonso Escobar Jaramillo, visited Bilbao, Vitoria and Brussels with the support of the Institute. The visit aimed to raise awareness of Nariño’s innovative peace efforts. It also sought to mobilise international support for a region whose stability and development are critical to Colombia’s peace efforts and hold significant implications for security across Latin America. Hearings were organised at both the Basque and European Parliaments, and meetings were held with the Basque Government and European Union (EU) Officials, including representatives from the European External Action Service, the Service for Foreign Policy Instruments, the DG for International Partnerships, and the DG for Migration and Home Affairs, among others. A working session with Brussels-based civil society organisations engaged in Colombia was co-hosted with the Colombian Ambassador in Belgium.

The Governor’s visit to Europe underscored the vital role of international partners, particularly the EU. European diplomacy can help raise the visibility of Nariño’s peace model and support it as a pilot initiative for conflict-affected border territories. Financial and technical cooperation – through the EU’s Global Gateway, bilateral partnerships, public-private ventures, and strategic partners like the Institute – will be essential to consolidate peace dividends, transition from illicit economies, and strengthen community resilience.

For over two decades, the EU has been one of Colombia’s most committed peace partners, investing over € 500 million in political and financial support, without considering the investments of its member states. Its backing was instrumental in securing the historic 2016 peace agreement and advancing its implementation. Colombia is one of the EU’s most notable successes in terms of conflict resolution and peacebuilding support. Today, with the CELAC-EU Summit in November on the horizon, it is vital to reaffirm that this is not the time to withdraw. Colombia, and territorial peace initiatives like those in Nariño, demonstrate that sustained, adaptable international support delivers security, development, and stability, benefiting not only local communities but also the wider region and the international community alike.

- عقد المعهد الأوروبي للسلام الجولة الرابعة للحوار بين العديد من المكونات السياسية في جنوب اليمن في العاصمة الأردنية عمان في الفترة من 5-7 يوليو 2025، ولقد شارك في الحوار ممثلين عن الجهات التالية: المجلس الأعلى للحراك الثوري لتحرير واستقلال الجنوب- حزب حركة النهضة للتغيير السلمي- الحراك الجنوبي المشارك في مؤتمر الحوار الوطني- جنوبيات من أجل السلام- الائتلاف الوطني الجنوبي- لجنة الاعتصام السلمي في محافظة المهرة- التحالف الموحد لأبناء شبوة- مجلس شبوة الوطني العام- مجلس حضرموت الوطني.

- استعرض المشاركون الأوضاع السياسية والاقتصادية والأمنية التي تمر بها المحافظات الجنوبية بشكل خاص واليمن بشكل عام وما تواجهه من تردي للأوضاع المعيشية والخدمات الأساسية وانفلات الأمن بالعاصمة عدن وباقي محافظات الجنوب.

- طالب المشاركون مجلس القيادة الرئاسي والحكومة والسلطات المحلية تحمل مسئولياتها تجاه المواطنين بشكل فوري ودون تأخير من خلال العمل على تجاوز هذه الأزمة التي تمس حياتهم ومعيشتهم وإصلاح السلطات المحلية التي كان لإدائها اثراً كبيراً في تدهور الأوضاع، محذرين من مخاطر استمرار هذا التدهور دون إيجاد الحلول الجذرية والشاملة لهذه الأزمة.

- أكد المشاركون رفض العنف واستخدام القوة المسلحة كوسيلة لتحقيق مكاسب سياسية او فرض واقع سياسي على أي منطقة أو محافظة، ورفض الاعتقالات والاخفاء القسري التي طالت العديد من الشخصيات السياسية والدينية والاجتماعية في العاصمة عدن، وفي هذا الإطار رفضوا رفضاً قاطعاً ما صدر من تهديدات في الأيام القليلة الماضية باستخدام القوة العسكرية لفرض واقع سياسي ضد أبناء حضرموت والذي يعتبر خرقاً جسيماً لقواعد العمل السياسي.

- عبر المشاركون عن تأييدهم الكامل لثورة نساء عدن وأبين ولحج المطالبة بتحقيق سبل العيش الكريم وتوفير الخدمات الأساسية بما في ذلك الكهرباء والمياه والصحة والتعليم والمرتبات وذلك خلال المظاهرات الأسبوعية التي خرجن فيها، وأدانوا عمليات القمع والاعتقالات التعسفية التي طالت عدد من النساء في عدن، ورفضوا رفضا قاطعاً عمليات الترهيب والتهديد والإيذاء الجسدي والنفسي التي تعرضت النساء لها، واهمية ضمان حماية النساء والناشطات من أي انتهاكات او مضايقات، واحترام حقوقهن بما في ذلك حقهن في حرية التعبير عن الراي والتظاهر السلمي، وطالبوا السلطات باتخاذ الإجراءات اللازمة لتلبية مطالبهن المشروعة، كما عبروا عن اسفهم من عدم إيلاء المجتمع الدولي الاهتمام اللازم بمساندة ثورة النساء.

- اتفق المشاركون من حيث المبدأ على انشاء منصة سياسية تضمهم جميعاً لتكثيف التشاور والتعاون فيما بينهم واتفقوا على متابعة هذا الموضوع خلال الفترة القادمة.

- ناقش المشاركون سبل مشاركة الجنوب في العملية السياسية وكيفية التعبير عن موقفهم للرأي العام اليمني وعلى المستويين الإقليمي والدولي، مع التأكيد على أهمية قيام دول المنطقة والمجتمع الدولي بدورٍ إيجابي في تحقيق السلام في اليمن.

- اتفق المشاركون على ضرورة قيامهم بإعداد رؤية للإصلاح السياسي والاقتصادي والأمني في ضوء التحديات التي تواجه المجلس الرئاسي والحكومة، والوضع المرتبك في العديد من المحافظات الجنوبية وتم تكوين فريق عمل لإعداد ورقة لمناقشتها بشكل عاجل خلال الفترة المقبلة، مع التركيز على أهمية تطوير النظام السياسي وتحقيق المصالحة الوطنية دون إغفال المحاسبة.

- أكد المشاركون ضرورة الإصلاح الاقتصادي على ان يتم بشكل تدريجي ومتوازن ويأخذ في الاعتبار المعاناة التي يمر بها الشعب اليمني، والتأكيد على ضرورة إيداع إيرادات الدولة بمختلف مصادرها في البنك المركزي، وكذلك أكدوا مخاطر تعويم الدولار الجمركي الذي سيمس مصالح المواطنين في محافظات الجنوب خاصة واليمن عامة في ضوء ان المزيد من تدهور الأوضاع قد يؤدي الى المزيد من التفكك، بل وربما الانهيار الكامل.

- أكد المشاركون أهمية توحيد التشكيلات العسكرية والأجهزة الأمنية تحت مؤسستي الدفاع والداخلية وفقاً لاتفاق الرياض ورفض أي تشكيلات مسلحة خارج إطار القانون.

- ثمن المشاركون اللقاء الهام الذي جمعهم مع عدد من سفراء وممثلي بعثات الدول الصديقة لدى اليمن بما في ذلك الاتحاد الأوروبي والولايات المتحدة والمملكة المتحدة وهولندا وكذلك مكتب المبعوث الخاص للأمم المتحدة في اليمن، لتبادل الآراء حول تطورات الأوضاع في اليمن بشكل عام والجنوب بشكل خاص.

- The European Institute of Peace held the Fourth convening of the Southern Dialogue Process in Yemen in the period of 5–7 July 2025 in Amman, the Hashemite Kingdom of Jordan. The dialogue included representatives from the following entities: Supreme Council of Southern Revolutionary Movement (Hirak), Nahdha (Renaissance) Movement for Peaceful Change, Southern Movement (Hirak) Participating in the National Dialogue Conference, Southern National Coalition, Committee of the Peaceful Sit-In in al-Mahra Governorate, United Alliance of the People of Shabwa, Hadhramaut National Council, Shabwa National General Council, and Southern Women for Peace Group.

- Participants reviewed the political, economic, and security conditions in the southern governorates and Yemen as a whole, noting the deteriorating living conditions, lack of basic services, and insecurity in the capital city of Aden, and other areas in southern Yemen.

- Participants call on the Presidential Leadership Council, the government, and local authorities to take immediate action to address the crisis affecting citizens’ lives and livelihoods. They emphasize the need to reform local authorities, whose performance has contributed to the worsening situation, and warn of the dangers of continued deterioration without comprehensive solutions.

- Participants reject violence and the use of force to achieve political goals or impose a political reality on any region. They condemn the arrests and enforced disappearances of many political, religious, and social figures in Aden. They also reject recent threats to use military force to impose a political reality on the people of Hadhramaut, which violates the accepted rules of political action.

- Participants express their full support to the women’s revolution in Aden, Abyan, and Lahj, who have been demanding a decent living and basic services such as electricity, water, healthcare, education, and salaries during their weekly demonstrations. They condemn the repression and arbitrary arrests of women in Aden and reject intimidation, threats, and harm against them. They stress the need to protect women and activists from violations and harassment and to respect their rights, including freedom of expression and peaceful protest. They call on the authorities to take the necessary measures to meet the women’s legitimate demands and express regret over the international community’s lack of support for the women’s revolution.

- The participants have agreed in principle to establish a political platform to enhance consultations and cooperation among them and to follow up on this issue in the coming period.

- Participants discussed ways for the southern Yemenis to participate in the political process and how to express their position to the Yemeni public, regionally, and internationally. They emphasize the importance of regional countries and the international community in playing a positive role in achieving peace in Yemen.

- Participants agree on the need to develop a vision for political, economic, and security reform considering the challenges facing the country’s Presidential Leadership Council and government, as well as the turbulent political conditions in many southern Yemeni governorates. A working group has been formed among dialogue participants to prepare a paper for urgent discussion, focusing on developing the political system and achieving national reconciliation while ensuring accountability.

- Participants stress the need for gradual and balanced economic reform, considering the suffering of the Yemeni people. They emphasize that all state revenues should be deposited in the Central Bank of Yemen and warn against floating the customs exchange rate of the US dollar, which could harm citizens’ interests in the southern governorates and Yemen as a whole. They note that further economic deterioration could lead to more disintegration, or even complete collapse of state functions.

- Participants also highlight the importance of unifying military and security forces under the government’s Defence and Interior institutions, according to the Riyadh Agreement, and reject any armed groups that operate outside of the law.

- Participants commend the significant meeting they held with ambassadors and diplomats representing friendly countries, including the European Union, the United States, the United Kingdom, and the Netherlands, as well as the Office of the UN Special Envoy for Yemen, to discuss developments in Yemen, particularly in the southern governorates.

This document was produced as part of an ongoing dialogue project facilitated by the European Institute of Peace to foster trust and convergence between political components in southern Yemen and to support the efforts of the UN Special Envoy for Yemen. This document has been produced with the financial assistance of the European Union. Its contents are the sole responsibility of the European Institute of Peace and can under no circumstances be regarded as reflecting the position of the European Union.

On 26 June 2025, The Institute hosted the event ‘A European Conversation on Syria’ in Brussels, together with the Belgian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, Foreign Trade and Development Cooperation. Held under the Chatham House Rule at the Egmont Institute, this meeting brought together senior representatives from the European Union and from several European States to reflect on the current situation in Syria and explore how European actors can contribute to short and long-term stability and peace.

The discussion started with an assessment of the major challenges facing Syria six months into its political transition, including sectarian tensions; measures to aid economic recovery; the need to unify security forces; inclusivity in political processes; transitional justice, accountability, and reconciliation; and broader regional security dynamics. Europe’s engagement should be predicated on a partnership approach that respects Syria’s agency and in full awareness of the significant capacity constraints at national levels across multiple fronts.

Despite these challenges, this moment represents a key opportunity to articulate Europe’s long-term strategic interests, encompassing key areas such as security, migration, trade, and resource management. In particular, the following were identified as priority areas for Europe to provide added value in support of Syria’s stabilisation and political transition:

- Institutional capacity building, which Europe can support by offering technical assistance and expertise to strengthen the capacities of staff within ministries and public institutions, so that they can deliver services and implement policies effectively.

- Supporting political inclusivity and human rights including by enhancing support for civil society actors – both inside Syria and within the diaspora – to strengthen their role in the political transition.

- Developing a trade and energy partnership, to reintegrate Syria into the global market and its economy. This can be achieved, in part, by reviving or reimagining a cooperation framework similar to the EU–Syria Cooperation Agreement signed in 1977. It could also involve expanding Syria’s sources of revenue and potentially integrating Syria into the European Energy market through the Great Sea Interconnector (GSI) project.

- Support for economic recovery through different avenues, which could include facilitating platforms which coordinate diaspora-led investment in small businesses, offering EU export guarantees, and contributing to job creation, cash-for-work schemes, and microfinance initiatives.

- Support stabilisation of Northeast Syria and Qamishli-Damascus Relations, by investing in infrastructure rehabilitation, particularly in the energy and water sectors. A visible and balanced European presence could also help mediate external pressures and support internal cooperation.

- Addressing the camps and prisons housing ISIS-affiliated populations in Northeast Syria where Europe can play a vital role in responding to humanitarian imperatives and reducing future security risks. This includes supporting the repatriation, rehabilitation, and reintegration of third-country nationals by engaging both the countries whose nationals remain in the camps and the Syrian Democratic Forces (SDF). Europe can also coordinate a response to the issue of male detainees held in prisons in Northeast Syria on suspicion of ISIS affiliation, including several hundreds of European passport holders.

The European Institute of Peace is proud to announce the launch of the website for our Environmental Pathways for Reconciliation (EPfR) project, which contributes to building a sustainable peace in Yemen by using the environment as an entry point for dialogue, reconciliation and trust-building among different parties at both the community and the national level.

The website contains comprehensive information on our team’s research and analysis work on environmental security and governance in Yemen and on the project’s consultations with the local population and engagement with decision-makers, with over 3,600 individuals involved across 13 governorates so far. Through these dialogue spaces that convene local decision-makers, traditional leaders, civil society, and subject experts, Yemeni citizens can identify locally led peacemaking solutions to address environmental risks and enhance resilience.